Humanitarianism and affect-based education: Emotional experiences at the Jean-Pictet Competition

For international lawyers seeking to promote compliance with international humanitarian law (IHL), some level of affective awareness is essential – but just where one might cultivate an understanding of emotions, and at which juncture of one's career, remains a mystery. This article proposes that what the IHL lawyers and advocates of the future need is an affect-based education. More than a simple mastery of a technical set of emotional intelligence skills, what we are interested in here is the refinement of a disposition or sensibility – a way of engaging with the world, with IHL, and with humanitarianism. In this article, we consider the potential for the Jean-Pictet Competition to provide this education. Drawing on our observations of the competition and a survey with 231 former participants, the discussion examines the legal and affective dimensions of the competition, identifies the precise moments of the competition in which emotional processes take place, and probes the role of emotions in role-plays and simulations. Presenting the Jean-Pictet Competition as a form of interaction ritual, we propose that high “emotional energy” promotes a humanitarian sensibility; indeed, participant interactions have the potential to re-constitute the very concept of humanitarianism. We ultimately argue that a more conscious engagement with emotions at competitions like Pictet has the potential to strengthen IHL training, to further IHL compliance and the development of IHL rules, and to enhance legal education more generally.

* The authors would like to thank Chris Kreutzner and Efrén Ismael Sifontes Torres for their excellent research assistance and Christophe Lanord for his helpful comments on a previous draft version of this paper. We are also grateful to the anonymous reviewers for their insightful reflections on our arguments.

As teachers of international law, in particular, we have in our care each year hundreds of students. For some of them, our course will be the only exposure to sustained reflection about global politics. There is a responsibility and power in this.

Gerry Simpson1

Introduction: To learn, to compete, to meet… to feel?

How will future generations prevent and alleviate the suffering caused by armed conflicts through law? International humanitarian law (IHL) – not unlike the phenomenon of war which it seeks to regulate – is deeply emotional both in its normative content and in action. Perceptions, feelings, culture, in-group belonging and a myriad of other extra-legal considerations shape the ways in which individuals and groups engage with IHL rules. Consequently, IHL in action rarely resembles IHL in the books. For international lawyers seeking to promote compliance with this body of law, some level of affective awareness is thus essential – but just where one might refine these emotional skills, and at which precise juncture of one's career, remains a mystery. In the law school setting, theoretical and applied training on emotions is the exception rather than the norm: law's affective dimension remains obscured to all but a very few students upon graduation.2 This article proposes that what the IHL lawyers and advocates of the future need is an “affect-based education”. More than a simple mastery of a technical set of “emotional intelligence” skills, what we are interested in here is the refinement of a disposition or sensibility – a way of being in and engaging with the world in general, and with IHL and humanitarianism in particular.

This article considers the potential for the Jean-Pictet Competition to provide this education. The Jean-Pictet Competition is a training course in IHL that engages participants in role-playing and simulations. Since 1989, universities from more than 100 countries have participated. In the past fifteen years, a central aim of the competition has been to “take law out of the books”. This makes the competition an excellent site of study to better understand the practice of IHL, and the interplay of emotions and law. The authors of this article have both participated in the Jean-Pictet Competition in various forms, and the discussion draws on this first-hand experience. The discussion is also informed by findings from a survey administered to 231 former competition participants in 2020, which will be the basis for our analysis.

Through a close study of emotions at the Jean-Pictet Competition, we will show that emotions play an important role in the global dissemination of IHL. Emotions matter not only for IHL training, but also for IHL compliance and the future development of this body of law. Tomorrow's IHL experts need to have a real grasp of fundamental principles (distinction, proportionality, precaution, etc.), and they must understand how IHL rules are implemented in the heated context of armed conflicts. For example, in moments of high stress, how does a commander decide whether to order or halt an attack? How are on-the-spot decisions made about deploying various means and methods of warfare? What does an ex ante assessment of a complex targeting decision look like without the benefit of hindsight? Each of these scenarios is inflected with strong emotions relating to fear, hunger, stress, resentment, grief, and so on. Teaching an “emotionless” IHL – however alluring this might be for its certainty – may do a disservice here, as it leads to misinterpretations, misunderstanding and a failure to grasp IHL's practical application. The practice-related aspects of the Jean-Pictet Competition, and especially its role-plays and simulation exercises, are thus ripe for investigation from an emotional perspective. As we will argue, the high emotional energy generated through the various interaction rituals at the competition achieves an unstated goal. This is the promotion of a humanitarian sensibility that will become an asset to participants in their personal lives and their professional futures – either within the realm of IHL or outside of it. We ultimately propose that a more conscious commitment and a stronger focus on the didactic importance of this affect-based education can increase the positive outcomes of the Pictet experience, enhancing its role as an IHL dissemination ground. We thus advocate for the competition to acknowledge and consciously deepen its affective dimension and, at the same time, for IHL university courses to integrate the competition's role-playing model as an antidote to traditionally emotionless legal teaching. Our conclusions also have implications that go far beyond Pictet, as we seek to make a more general point about emotions in legal education.

The discussion is structured as follows. The first part provides an overview of the Jean-Pictet Competition and presents it as a training space with both legal and affective aspects. The second part explores two key themes that emerged from participant experiences at Pictet: emotions before, during and after the competition, and role-plays and simulations as a site where law meets emotion. The third part advocates for a “law and emotions” approach to the Pictet experience, and to IHL pedagogy more generally. This section delves deeper into individual and collective emotions at the competition, and also examines the impact of the Pictet experience on participants’ career aspirations. We present the competition as a site at which students “become humanitarian”, joining a global humanitarian community which can be understood as a type of “affective community”. This transformation occurs by means of numerous implicit sociological phenomena – including interaction ritual, emotional energy and circulation of affect – which we argue need to be dealt with explicitly and amplified for a stronger impact. The concluding section suggests further creative ways forward in the project of delivering an affect-based education to those who would seek to disseminate, promote and ensure respect for IHL.

The Jean-Pictet Competition as a site of law and emotions

Academic legal education might seem far removed from the active conflict zones that studies of IHL typically engage with, especially when compared with other pedagogical efforts like military trainings, which tend to focus on field simulations. Yet these academic spaces, too, are worthy of study as settings in which IHL rules are implemented in practice.3 The Jean-Pictet Competition experience is saturated with individual, interpersonal and group emotions that shape the way in which individuals – in this case, the potential IHL lawyers of the future – understand and engage with law. Probing the emotional experiences of participants in the competition has the potential to achieve the following aims: improving and enhancing the Jean-Pictet Competition as it evolves over time; informing the IHL dissemination efforts of States and organizations such as the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC); and enhancing compliance with IHL rules globally. Beyond these tangible gains in the field of IHL, student experiences at the competition offer insights for legal education, specifically regarding the way in which law students are trained to become lawyers in the university setting across different cultures and countries.4

The “Pictet experience”

The Jean-Pictet Competition is widely perceived as one of the best examples of efficient practice in disseminating IHL knowledge amongst students at universities.5 But what is the “Pictet experience”, exactly? The Jean-Pictet Competition is a training event for law students from all around the world,6 which aims to disseminate the principles and values of IHL through a dynamic and immersive role-play simulation.7 Every year, the Committee for the Jean-Pictet Competition (Comité pour le Concours Jean-Pictet, CCJP), a not-for-profit association with twenty-seven members globally, organizes the competition in a different location. A call for registration is launched, and interested teams that apply are carefully selected after the submission of short essays (answering three questions) which undergo several rounds of evaluation. There are typically forty-eight teams in each edition of the competition, usually from five continents.

Distinguishing it from other competitions on international law, the Jean-Pictet Competition has some unique features.8 It was created in order to promote a more dynamic way to teach IHL, showing the practical importance of that body of law and the real-life challenges involved in implementing it in times of armed conflict. The selected teams meet for a one-week competition from a Saturday evening to the next Friday evening, in which they must assume the roles of various actors engaged in a fictitious armed conflict. In addition to the diverse backgrounds and qualification levels of the teams, there is an intergenerational aspect: the competition is presided over by an evaluation panel or “jury” formed of eminent experts in international law and in humanitarian affairs (who may be former Picteists themselves), convened every year by the CCJP. The jury's presence inculcates a professional and competitive atmosphere throughout the proceedings, adding a sort of “upscale” flavour and exposing participants to encounters with more seasoned lawyers and humanitarians.9 This presents an important opportunity for cross-generational engagement on IHL.

The method and pedagogical approach of the Jean-Pictet Competition focus more on oral interactions than most other law moots, where written memorials or pleadings are required.10 At the Jean-Pictet Competition, students play the roles of diverse actors (such as States, military personnel, humanitarian workers, political officers, armed group members and lawyers) in the context of a fictional case scenario that progresses throughout the days of the competition. The development of the case scenario involves an important surprise element. In the weeks prior to the competition, only some very general and abstract hints are provided to the teams. This generally acquaints them with the fictitious region where the armed conflict will take place and allows them to start elaborating hypotheses on the relevant topics. The details of each edition's case study, however, remain unknown until the first day of the test, once participants have arrived at the venue. The scenario is then progressively developed day by day, and no team can foresee the direction it will ultimately take. Despite its fictional nature, the scenario is always closely associated with real-life precedents and routinely engages with global events that are unfolding at the time of the competition. The March 2020 edition in Indonesia, for example, dealt with COVID-19. This dynamic approach aims to foster a contextualized and practical understanding of the application of IHL in armed conflict.11

While the emphasis is on practical implementation, participants are still required to engage extensively with IHL doctrine and theory as part of their preparation. The late reveal of the case study also requires them to familiarize themselves with the different areas of public international law (PIL) that are relevant in armed conflicts, such as international criminal law, international human rights law and international refugee law. Although the overall focus of the Jean-Pictet Competition remains on IHL, some tests may elevate these other branches of PIL over IHL in terms of importance.

As noted, no detailed information on the case study is given to the teams before the week of the competition. However, ahead of the competition the CCJP administrator sends participating teams basic training documents on relevant topics to help them get abreast of legal matters. In addition to legal substance, the training documents highlight the importance of teamwork and practical skills related to negotiation and role-play. These materials convey to participants that they must keep the legal aspects of the assigned topic at the forefront of their minds when preparing, yet they also need to be creative in the broader strategies they deploy once the competition is under way. Participants are thus invited to strike a balance between strengthening their theoretical legal knowledge and honing their ability to communicate and negotiate in challenging circumstances. A grasp of the “extra-legal” will be especially important when participants prepare to accurately embody their assigned simulation roles. The emphasis on interaction with others across the competition also provides an opportunity for the contestants to engage with persons from diverse backgrounds, the Jean-Pictet Competition being a place that produces strong interpersonal links and long-lasting friendships. These connections might eventually shape the professional careers of those who participate, but they also have intrinsic value in terms of relationship- and community-building.

Objectives of the Jean-Pictet Competition

The Jean-Pictet Competition has three stated objectives: to learn, to compete and to meet. The “learn” criterion includes not only IHL and related areas of international law, but also skills that are not always addressed in university teaching such as public speaking, teamwork, interaction with different types of interlocutors, and stress management. Pictet participants are evaluated by jury members on the following assessment criteria: legal aspects, strategic skills and interaction with others.12 According to the regulations of the competition, the strategic skills component includes the following four features. First, demonstrated understanding of the simulations: “the capacity to position oneself within the given scenarios … [and] the ability to understand the complexities of the events and the assigned roles during the various simulations”. Second, ability to argue: “persuasiveness in presenting arguments, use of the law in creative and innovative ways, appropriate combination of rational analysis with emotion and passion”. Third, commitment: towards the competition, the simulation and, when appropriate in a simulation, the spirit of IHL. Fourth, oral communication skills: including the ability to be convincing, articulate and logical; the ability to convey feelings when appropriate in simulations; the capacity to communicate across cultures; and the ability to translate complex issues and ideas into understandable concepts.

These components need to be broken down in order to examine the relevance of feelings and emotions. In the feature related to demonstrated understanding of the simulations cited above, there is a hint that empathy and emotional intelligence might be important, as the participants must position themselves in the scenario and understand the assigned role. There is an explicit reference to “emotion” in the ability to argue feature, and to “feelings” in the oral communication skills feature. It may be argued that a role for emotions is also implicit in the reference to the “spirit of IHL” in the commitment feature. The competition envisions that participants will bring emotion and passion into the case scenarios along with legal/rational arguments, that they will possess the appropriate judgement regarding when and how to convey feelings in the simulation exercises, and that they will embody the spirit of IHL through their behaviour, comportment and expression. Presumably, this last aspect requires participants to demonstrate a proclivity and affinity for humanitarian values such as compassion. This point will be revisited later in the article.

The interaction with others component cited above refers to the importance of teamwork and cooperation, as well as respect for the neutral humanitarian space in which the competition is organized, and the ability to listen to others within and outside of the team. The issue of (active) listening could have an important emotional component, especially if one links it to paying attention to those in an out-group or outside of the team. We could scrutinize a further affective dimension here, which relates to cross-cultural engagement: in a scenario in which two competing Pictet teams come from States that are involved in an armed conflict with each other in real life, attending to the cultural aspect could help to enhance the responses and the determination of the teams. At the same time, emphasizing a cultural component could serve to heighten tensions – perhaps even when a team does not come from either of the actual conflict States but its members have strong feelings about the conflict. Accordingly, it is important to think of cultural sensitivity in a broader sense here, as a concept that entails the promotion of open-mindedness, empathy and impartiality. As a more subtle goal, then, the Jean-Pictet Competition can encourage contestants to empathize with others who in real life are often pictured as the “enemy”. The engagement of seasoned professionals, for example as members of the jury, is important here for modelling diplomatic behaviour. These professionals can share concrete experiences, offer advice and convey the importance of cross-cultural empathy and understanding, showing participants that this is an essential disposition in the arena of international law and politics. The concepts of “humanitarian space” and neutrality are also important for the present discussion, and they will be examined further below.

While the Jean-Pictet Competition clearly has an affective dimension, the extent to which student participants actively prepare to succeed in this aspect has not been explored. Additionally, the relevance of intra- and inter-group dynamics to engagement with law at the competition has not been well understood. As we will now show, attending to these extra-legal elements is fundamental to fully understanding the competition and its longer-term impact.

Feeling IHL: Participant experiences at the Jean-Pictet Competition

In 2020, we administered a survey to 231 former Pictet participants. The survey was open to all individuals who had participated as student team members in the Jean-Pictet Competition since its inception in 1989. This group includes some 2,700 individuals worldwide, out of more than 4,000 alumni. The survey was administered in English, French and Spanish using Qualtrics.13

The aim of the survey was to uncover the way in which IHL and emotions interconnect, by inviting participants to reflect on the emotional dimensions of their Pictet experience. While we knew it would be difficult to accurately identify specific individual emotions,14 we hoped to broadly map the competition's emotional terrain and to get a sense of what participants, individually and collectively, were feeling at various junctures. To develop the specific questions for the survey, we drew on our direct experience with the competition: Rebecca has been on the jury, and Emiliano has a long-standing involvement that includes being in the scenario “kitchen” and serving on the CCJP since 2012. Additionally, the survey is informed by our observations and conversations that took place over a week-long period during the 2020 Jean-Pictet Competition in Indonesia. This engagement led to the discovery that students seemed to “become humanitarian” at the competition, generating a new set of survey questions about career aspirations.

In what follows, we will draw on some of the survey responses to demonstrate that emotions influence IHL and play a crucial role in competitions such as the Jean-Pictet. The next two subsections respectively explore (1) emotions at different stages of the competition and (2) role-plays as a site where law meets emotion.

While feelings and emotions are clearly engaged throughout the Pictet experience, the intensity and the specific feelings which are aroused at various moments will depend on several factors – in particular the stage of the competition and the role one is assigned to play. To understand the connection between IHL and emotions at the Jean-Pictet Competition, it is essential to identify the precise moments of the competition in which specific emotional processes take place. This is the goal of the first section of the discussion. Here we attempt to capture a snapshot of emotions, an endeavour complicated by the fact that emotions are not in a static state. What we find is that (experiences of) emotions are dynamic and in flux, influenced by the different stages of the competition. Emotions like excitement or fear thus predominate according to the circumstances in which participants find themselves, how they perceive those circumstances, and what they expect is going to happen next. For example, preparation for the competition may entail high levels of anticipation; interpersonal engagement with other teams during the competition may give rise to strong feelings, both positive and negative; and individual expectations and fears might further intensify as participants approach the competition's final stages. There are relational and collective elements to consider as well, as participants’ own emotional experiences are shaped in part by (their assessments of) the emotional states of others – within their team, from other teams, from the jury, and so on – and how these others view or respond to them.

Another important factor shaping emotions at Pictet relates to the role-plays and simulations. The second section of the discussion considers how participants engage in their assigned roles and how the different scenarios they confront can produce varying emotions. We contend that the ability of individuals and teams to grasp their assigned roles, and to develop appropriate strategies that reflect these roles, is decisive in shaping the emotions that arise.

The outcomes of the survey and these reflections allow us, at the end of the section, to advance various proposals on the need to embrace affect-based education in order to promote humanitarian awareness and train future professionals in the field.

Emotions before, during and after the competition

While emotions evidently flow through every single person who participates in the Jean-Pictet Competition, understanding the role of emotions in a more in-depth way requires us to examine the personal experiences and backgrounds of each participant. In this section, we consider the development of emotional intelligence skills (i.e., skills that can help students to be persuasive orators) and holistic affect-based strategies relating to the teaching, dissemination and promotion of a more refined disposition or sensibility towards others. This latter sensibility aspect is grounded in IHL's humanitarian aims, and it links to the notion that participants are joining a global humanitarian community.15

What interests us presently are the feelings that are most likely to be experienced at specific moments of the Jean-Pictet Competition. Our aim in exploring emotions in this way is to reflect on how they might be better harnessed at each stage in order to enhance the overall educational value of Pictet. It should be acknowledged that some emotions discussed here would arise in any international law competition. Indeed, this fact enhances the relevance of our argument beyond Pictet and the IHL field; we expect that a similar temporal approach could help illuminate emotions at other types of competitions.

Starting with the advance preparation that participants engage in before they travel to the competition, a participant from the United States described the environment in which she prepared at her home institution as stressful. This underscores the fact that the competition as such does not simply start at the inaugural ceremony which officially opens the week – well before they arrive, participants will already have experienced and navigated anticipatory emotions while preparing in their respective local environments. Before the competition officially begins, then, feelings like stress, insecurity, panic and nervousness, but also optimism, excitement and joy, will have a critical influence on each of the participants’ minds and bodies. There are material aspects to participation that also merit consideration here: while some universities pay for the competition (allowing their students to focus more on studying), other participants need to raise money to pay for team travel. We anticipate that the latter students have less time to devote purely to preparation and are likely to experience higher levels of stress in advance of the competition. A further point here is that for many participants, the Jean-Pictet Competition is a poignant emotional experience because it represents their first time travelling internationally.

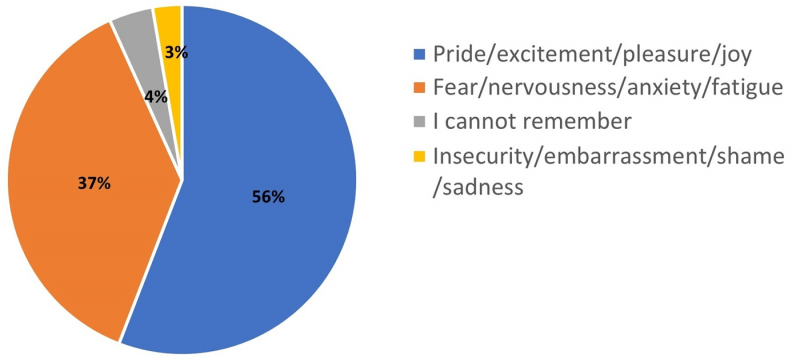

Our findings show that there are different kinds of emotions, expressed in a variety of ways, arising before and after the opening night ceremony. In this matter, the survey found that almost 56% of those who answered the question “Which feelings were strongest for you in the weeks prior to the competition?” said they felt highly positive emotions such as pride, excitement, pleasure and/or joy (see Chart 1). But it is interesting to note that a high rate (almost 37%) of respondents to this question also described less positive emotional experiences related to stress: they felt fear, nervousness, anxiety and/or fatigue.

Chart 1. Responses to the question: Which feelings were strongest for you in the weeks prior to the competition?

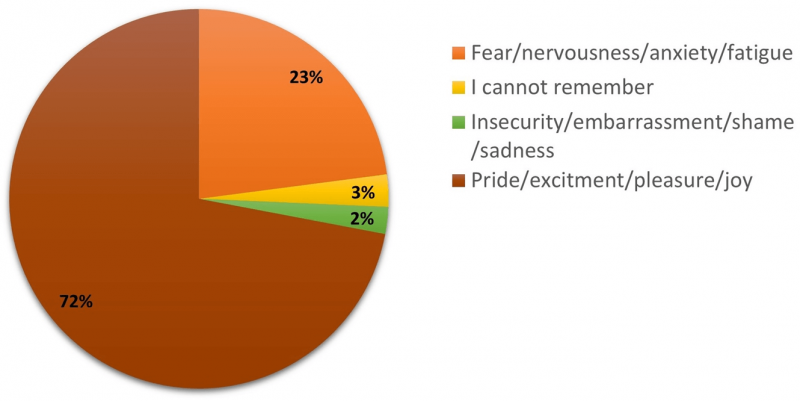

Once the opening ceremony begins, however, we find that those negative emotions subside. On the question “Which feelings were strongest for you on the opening night of the competition?”, almost 72% of participants indicated that they felt excitement, pride, pleasure and/or joy (see Chart 2). This disparity can be explained with the feeling of “overjoy” and expectation that the ceremony produces in the participants. Where nervousness and fear previously prevailed, a slight feeling of excitement and anticipation soon arises – perhaps combined with some relief that things are going well.

Chart 2. Responses to the question: Which feelings were strongest for you on the opening night of the competition?

A further example of these different “opening night” emotions can be found in the experience shared by one of the participants from Argentina, who said that she felt excitement walking with the other team members to the competition venue. Another strong emotion during these moments prior to the opening ceremony of the competition is a sense of responsibility, as shared by a participant from Belarus.

These mixed feelings are perfectly compatible with the expectation of participating in a prestigious and enjoyable, yet challenging, international law competition where participants’ knowledge will be tested and where they are representing their home institution and even their country – which, in their own perception, they could “make proud” or, equally, disappoint or “let down”. Quite often, the pressure from a specific university to perform well, or the self-imposed pressure to be a good representative of one's own country, needs to be considered as a cultural demand that students must deal with. This is an important aspect of cross-cultural engagement at the competition, reminding us that each team (and the members within it) might bring a very different perspective on what is at stake.

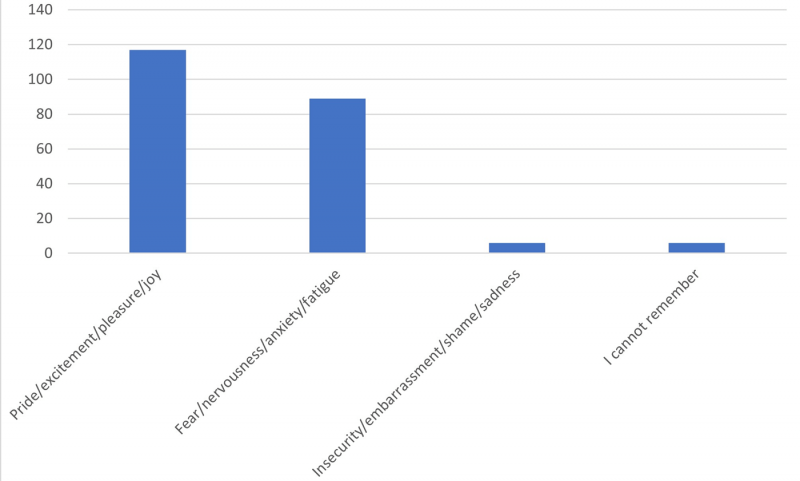

As soon as the competition kicks off with the first role-play exercise, the teams assume their respective roles and begin to interact amongst their members and with other teams. The performance aspect now also begins, as the jury starts observing, asking questions and evaluating the teams. Frequently, the hypothetical situations that are played out are complex. Although the analysis of role-playing and simulations will be deferred to the next section, it is worth noting the predominant emotions shared in the survey regarding this stage of the competition. Out of the 218 responses given to this question, 117 (54%) said that the strongest feelings during the first role-play were once again excitement, pride, pleasure and/or joy, while eighty-seven (40%) stated that fear, nervousness, anxiety and/or fatigue were stronger for them (see Chart 3).16

Chart 3. Responses to the question: Which feelings were strongest for you while you were competing?

These emotions are connected to how participants felt during the advance training that took place before the competition began. More positive emotions were present among those students who had been exposed to specific information on how the simulations work – for example, through interactions with alumni of previous editions. Prior experiences thus play a key role in the way the contestants feel and express emotions during the competition: those teams that were able to rehearse based on the experiences shared by friends or peers who had been former Picteists felt more confident and experienced more pleasurable (and less stressful) moments at the beginning of the competition. To address this gap, the CCJP has decided to include general ice-breaker workshops on Sunday morning, which are delivered by some of the invited jury members or CCJP members. A first “mock test” now also takes place on Sunday afternoon before the “real” competition starts on Monday morning. This familiarizes participants with the different formats they will experience, and it provides those who had less advance coaching with the chance to express doubts and ask questions. As part of these general workshops, the CCJP also introduces the practical aspects of the competition, explaining its purposes and offering a network of support. An important part of the latter is the appointment of tutors – along with volunteers, most of whom are former participants – who accompany the teams during the week and provide them with tailored feedback on their performance. Notably, tutors are not allowed to discuss legal issues with their assigned team; their assistance is limited to non-legal matters such as role-playing techniques or communication. As the survey reveals, the tutors’ role is essential in assisting participants to navigate their emotions throughout the week.17

In addition to the points regarding advance preparation and support noted above, each participant's lived experience of the competition will be shaped by the way that they prepare to answer questions from the jury, the level of cohesion between team members, and the self-confidence they feel and display.

Another important element that influences emotions during the competition (which is reflected in the fact that members of different teams often report having different emotions) has to do with evaluation of performance: that is, participants’ reaction to the jury's decision about whether their own team will progress successfully to the next round. Technically, the Jean-Pictet Competition is a place to share and enjoy, with no formal ranking of participating teams provided at the end. Nonetheless, it is impossible to deny that there are ultimately winners. Emotions like anxiety, a rush of adrenaline, disappointment and joy run high during the week because of this. These emotions spike when the jury announces which teams will advance into the semi-finals and finals.

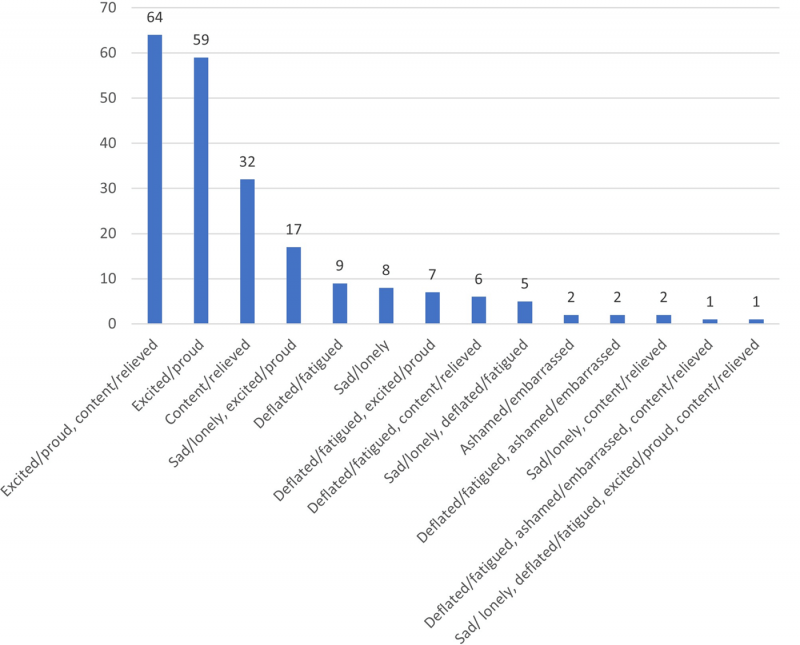

As the competition concludes, one might expect that there would be two different kinds of emotions among participants: sadness and joy. The team winning the edition would be overwhelmed by a strong set of (positive) emotions, ranging from excitement to pride, whereas all those teams who did not manage to win would feel somewhat disappointed. Notably, however, our survey reveals pride and satisfaction as the predominant kind of emotion felt by all participants when the competition is over. In answer to the question “Which two options best describe how you felt upon returning home from the competition?”, almost 72% felt excited, proud, content and/or relieved, while only 18% felt sadness, loneliness, shame and/or embarrassment (see Chart 4).

Chart 4. Responses to the question: Which two options best describe how you felt upon returning home from the competition?

These numbers do not track with the proportion of participants who “win” the competition, meaning that positive emotions were not ultimately contingent on outward success.18 The fact that satisfaction and pride are the main feelings of participants when the Pictet experience is over – regardless of the result – suggests that the experience of participating in the Jean-Pictet Competition is intrinsically rewarding. Students know, as they also report in the survey, that simply being part of Pictet can influence the careers of everyone who participated. They ultimately feel part of a privileged group of law students who have been able to take part in a competition where they have learned to take the law out of the books. As a participant from Venezuela shared, “the Pictet has been the most beautiful international academic experience of my life”. It is not every day in a law school setting that one hears these kinds of exuberant statements from students, and this points us towards the possibility that there is something special about the Pictet experience that would be desirable to amplify and replicate elsewhere.

These participant statements attest to positive outcomes related to the Jean-Pictet Competition as a whole, an experience interspersed with “meaningful rituals”. These rituals are an essential part of the competition, and they include the welcome ceremony, document distribution, tests, tutors’ meetings, jury debriefing, semi-finalist announcements, party night, semi-final and final rounds, and closing ceremony. Separately and collectively, these rituals generate significant moments that combine to create a positive community based on shared values, collaboration and in-group understanding. These formal rituals are complemented by the simulation aspect of the competition, which gives rise to specific emotions that are unique to Pictet.

Role-plays and simulations as a site where law meets emotion

The Pictet method, as established above, is premised on the idea of immersion through simulations based on real-life scenarios. Those in charge of developing each edition's fictional case study – the “kitchen” that “cooks” the evolving story for the week and assigns specific tasks for each test – take the emotional background of the role-play very seriously. The roles assigned to teams are not random or arbitrary; they are carefully designed to reflect the reality of armed conflicts, and to expose students to the motivations, behavioural constraints, resources and interactions of institutional actors in armed conflicts.19 The underlying thought here is that to truly understand the dynamics of IHL practice, one must have an opportunity to adopt the persona of an actor in an armed conflict – even if only for a fictional activity.

As students step into their assigned roles, their ability to manage felt and expressed emotions during the simulations constitutes an important element of their Pictet participation. To be effective, participants must be able to properly embody the role and feel like they are “stepping into the actor's shoes”. In this sense, an Argentinian participant said that the key to their success when playing the part of someone who was “abducted” (i.e., taken out of the room by a jury member performing the role of a terrorist) was that they were able to channel feelings of anguish and fear that they imagined one might feel in this situation.20 Some participants likewise reported that playing the role of a humanitarian actor made them more empathic to the different challenges that humanitarians face in real-life armed conflicts. Closely relating to (the individuals playing) victims in the course of the tests also helped them to understand how conflicts affect individuals and communities.

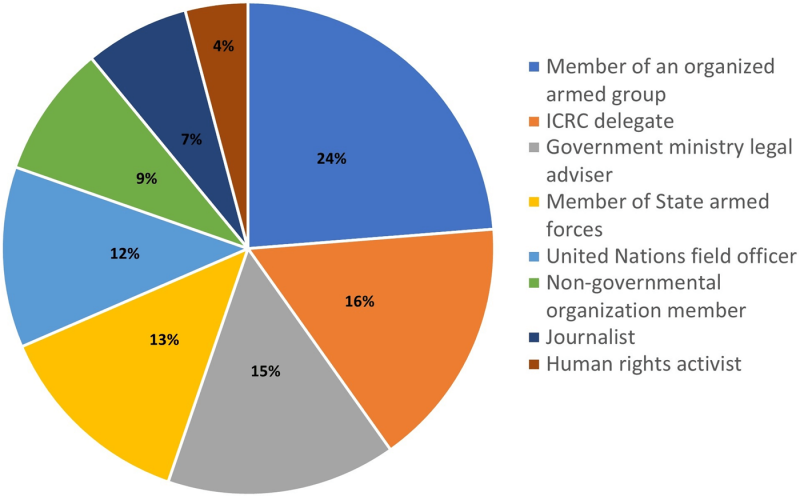

As the simulations require participants to assume the role of several different actors, some discomfort is inevitable. Our survey shows that there are certain roles which participants believed would be difficult for them, and these tended to be the more operational and less straightforwardly “legal” roles (see Chart 5).

Chart 5. Responses to the question: What kind of character, from the list below, would you find it most difficult to play?

Acting as a member of an armed group, for example, is a role which most law students are not familiar with and are not trained to do; some would be unsympathetic to it as well (see below). This point held for operational military actors more generally. While that is perhaps unsurprising, some also found it difficult to perform as legal advisers (i.e., to political decision-makers), NGO representatives or ICRC delegates – roles one might expect to be closer to the hearts of Pictet competitors. Participants explained that this was because legal academia has never given them tools to “use” or “apply” law in practice, and they thus felt unequipped to apply law concretely in the field.

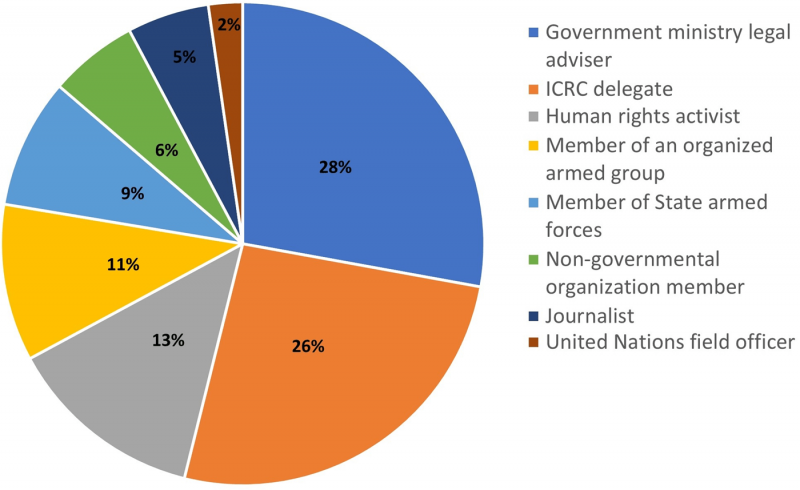

When asked about which of the roles they found the easiest to play, most of the participants identified government ministry legal adviser, ICRC delegate and human rights activist as their best options (see Chart 6). They felt that these roles required them to channel their legal knowledge more directly – though one could argue that there is a slight contradiction here with beliefs about some field-oriented advisory roles being too intimidating.

Chart 6. Responses to the question: What kind of character, from the list below, would you find it easiest to play?

These findings show that assuming unfamiliar roles presents a clear pedagogical opportunity, as it forces students to jump out of their comfort zone, adopt different perspectives and put law into action. Claims about being unprepared to apply law practically in the field – whether in relation to humanitarian practice or technical applications of international law – also point to a gap in global legal education more generally.

A point of relevance for emotions is that in certain cases students may wish to reject or distance themselves from their assigned role because they disagree with the stance or interests that they are obliged to embody and defend. Highlighting this dynamic, a participant from Serbia recalled feelings of embarrassment and guilt when playing the role of someone who was responsible for committing illegal actions. In the same vein, a participant from India described having to balance difficult emotions in a simulation where she was required to prosecute a child soldier for committing war crimes.

It is not only the assigned role that is relevant to the way the participants feel and express their emotions, but also the context(s) in which they must operate. Sometimes, the challenge that is presented comes from confronting an unexpected situation or dynamic as the scenario unfolds. These surprise moments can trigger emotions and impact the way that participants perform. A participant from India thus described feeling “tough emotions” during a preliminary situation in which jury members played the part of terrorists. A participant from Nepal also reported feeling “sick and a major adrenaline rush” when she entered a room of actors playing the part of victims who had been harmed, injured or killed.21 This exposure led her to reflect on real-world armed conflicts and their impact on human life: she explained that the simulation triggered “empathy for the situation in current armed conflicts around the world”. Finally, a participant from Singapore said her emotions were triggered when she encountered an individual (performed by a jury member) who was crying, upset and seemingly terrified during a simulation. This experience, according to the participant, “reminded us to go back to the basic instincts we have as humans and to show empathy and sensitivity, before thinking with any other legal hats on”. This last point is noteworthy because it suggests that participants sometimes make conscious decisions to try to separate law from emotions; they lead with their feelings and de-prioritize the legal element.

The above examples demonstrate that engaging in role-play shapes the (mixed) emotions that participants experience throughout the competition. Our survey also attests that there is a further emotional aspect that unfolds around the simulations, one we might expect to find at any moot court competition. As teams strategize, develop their arguments, get ready to take the floor, and organize the speaking responsibilities of each team member for oral presentations, they keep the assigned scenario in mind. But the survey also shows that participants experience feelings one would expect in any kind of (semi-)public performance of this nature: nervousness and anxiety are present in almost every collected testimony. As the pressure of performance mounts, team spirit and the ability to help and rely on each other also become essential assets, both for the team's performance as a whole and for what goes on at the individual, personal level.

The various types of tests which are deployed during the week of the competition call on participants to engage specific strategies and skill sets. Relevant activities include negotiation, mediation, advising, fact-finding, decision-making and pleading, all of which could be relevant within and beyond IHL practice. During these formal interactions, emotions are generated within a global and multigenerational community made up of students and jury members. The more informal interactions that accompany the tests also create a deep sense of solidarity in terms of emotions, based on a shared understanding of the importance of humanitarian values such as compassion, empathy and affection. Acknowledging this common ground helps to overcome possible negative emotions that arise in armed conflicts, which participants with direct exposure to armed conflicts might also have experienced first-hand. The neutral space of the Pictet – based on the “learn, compete, meet” motto – plays a crucial role here, helping to neutralize the affective impact of war and potentially enabling participants to overcome traumatic feelings by providing them with a safe space to perform, interact and reflect.

Further to the issue of performance, evaluation is always at the forefront of participants’ minds. This is the case regardless of whether they will be formally ranked at the competition's conclusion. As teams are aware, the way that they approach their assigned role and the context in which they are immersed is decisive to their evaluation. While there are always several plausible legal arguments that can be deployed in the universe of fictional Pictet scenarios, the arguments deployed must be appropriate to, and contextualized for, the assigned role. It is not unusual for confusion about the scenario and/or unwillingness to take on a role to produce a misstep in a team's performance; awareness of this possibility introduces a trepidation or fear element for participants. Such errors can happen at any stage of the competition, and when they do, they tend to destabilize team cohesion. A US participant thus said that she felt “embarrassed” after her team prepared for the wrong part due to an incorrect interpretation of the assigned task. The risk here is that individual members may lose trust in, turn on or blame each other in these moments of embarrassment – dynamics that can reverberate across subsequent competition events. If thoughtfully discussed within the group, however, tackling these negative moments of resentment and disappointment at the Jean-Pictet Competition may increase mutual support amongst team members, as explained by a former participant who is now an expert in the field.22 Trust and inter-reliance will equally be important for participants outside of the competition, should they embark on professional lives as IHL lawyers, humanitarian practitioners or other related roles. A small team of humanitarian negotiators, for example, must support one another if they are to work coherently as a team to advance their agenda – including, and perhaps especially, where one of them makes a mistake.

To sum up the above, the emotions experienced by the participants during role-play exercises at the Jean-Pictet Competition matter. While this appears to be a simple and somewhat obvious claim on the surface, stating it emphatically is an appropriate starting point for the arguments that will be advanced in the rest of the discussion. These emotions are the expression of the participants’ values and beliefs, which interplay with their theoretical knowledge of IHL and PIL in general. There are certainly some roles which will be easier to represent because they align with the values commonly shared by IHL students, while other roles may be more challenging due to the threat they pose to the ethos of participants (or because they are deemed too “operational”). Playing new roles in each test within the competition requires participants to adapt their own mindsets and perspectives to reflect the thinking, assessments and interests of various stakeholders in an armed conflict. Participants cannot avoid challenging themselves, questioning their own values and the limitations of their point of view. By displaying and expressing the emotions that they project onto the assigned role, participants potentially get closer to experiencing what others feel and think. This offers an empathetic way of understanding the plurality of possible positions that different people might adopt on the same topic or problem. It also helps students to grasp that IHL cannot be confined to some kind of abstract legal realm, and that on many occasions the real-life use of legal arguments should be complemented by other (rational, emotional) strategies in order to achieve a concrete goal under specific circumstances. As we will address below, this could even imply going as far as using law in ways that challenge or contradict one's fledgling humanitarian values.

This discussion has shared the findings from our Pictet observations and survey, which establish that emotions and feelings play a key role at the Jean-Pictet Competition. This is the case not only with respect to the development of strategies employed by the participants in each test, but also when teams are determining the circumstances in which a non-legal approach could better help them to realize an objective. These findings establish that an affect-based education serves as a didactic tool that can present students with concrete dilemmas and experiences, offering a better understanding of the realities of armed conflict and the interactions between stakeholders in times of war.

This engagement with the survey will now be complemented by a more theoretical examination of the extent to which making use of the emotional dimension can improve the Jean-Pictet Competition's role as an IHL dissemination ground. As we will discuss in the next section, paying careful attention to the role of emotions can help us to harness the potential for role-playing activities to shape the world views of future humanitarians.

Becoming humanitarian: The impact of the Jean-Pictet Competition on law student futures

This section considers the Jean-Pictet Competition as a formative initiation of membership into a broader global humanitarian community. It examines how the experience shapes participants as future IHL lawyers, influencing their engagement with law at the competition itself and in their (projections of) future careers. The three subsections respectively explore the reported impact on student career trajectories; how a humanitarian sensibility is acquired or developed through the competition; and Pictet as a site of interaction ritual.

To set the stage, parallels can be drawn between the emotions aroused during the Jean-Pictet Competition and those related to humanitarian work itself. Of course, the tests provide students with a safe simulation which, at the end of the day, cannot be compared to real-life missions where their lives might be at risk – but similarities in affective dispositions may nonetheless be triggered here, if not in intensity then at least in kind. For example, anxiety related to preparing for the competition is not so different from some feelings which are experienced before embarking on a mission; the fear of failing during the tests can be mirrored by the fear of having access to detainees thwarted; and unease about letting down one's university or country has echoes with anxieties about disappointing victims of an armed conflict. While, as noted, the stakes are clearly higher in actual humanitarian field work than in a simulated role-play, we find that role-play participants also experience these heightened emotions at a personal level. Indeed, we would argue that the artificiality and low stakes of the Jean-Pictet Competition potentially contribute to feelings of shame and embarrassment: when a participant performs poorly, she might have the sense that she should have done better because this is a carefully controlled and simulated scenario. These parallels with professional practice suggest that a more intentional approach to affect-based education can provide tools for professional training within and beyond the humanitarian sector as well.

Impact of the Jean-Pictet Competition on career choices

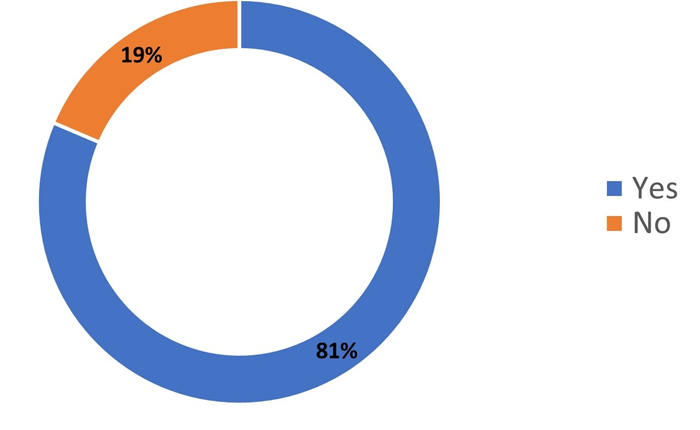

From the survey results, we have identified that an overwhelming 81% of respondents believed that having participated in the Jean-Pictet Competition impacted their plans for their legal careers (see Chart 7). For a substantial number of participants the experience crystallized their interest in pursuing humanitarian work, for example with an organization such as the ICRC; several participants agreed that the competition helped them to decide that they wanted to specialize in the field of IHL and the regulation of armed conflicts. The Pictet experience motivated these participants to structure their academic and professional choices towards graduate projects and areas of work or research that relate to IHL.

Chart 7. Responses to the question: Did your experience at the competition impact your plans for your (law) career?

These findings attest that the competition boosts interest in IHL as a field of specialization, one that some participants did not even know existed prior to attending the competition. This applies not only to students who had not yet fleshed out their career aspirations, but also to those who had been quite set in their plans: some participants had been inclined to pursue a legal career in other specific areas before participating, and the competition gave them a new perspective. One participant from the UK, for instance, modified her career path after participating, and reported that she is now currently working for the ICRC. Similarly, a participant from Sri Lanka said that Pictet motivated her to change her professional focus and pursue work as a humanitarian officer at the United Nations (UN) or ICRC. She was considering this now instead of academia, because she “wanted to do something to stop war or even to protect the people who are suffering”.

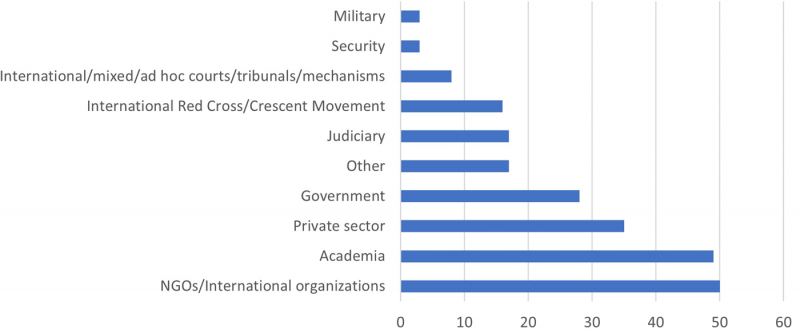

The effect of the Pictet experience on career choices is also evident when analyzing the current fields of work (and past professional experience) of those who answered the survey.23 Out of the 228 respondents who replied to the question “What describes best your current field of activity?”, the vast majority are now working in NGOs, international organizations and academia, even if not always directly focused on IHL topics;24 sixteen of them are currently working within the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement (see Chart 8). As indicated by one participant, “it was mainly due to the Jean-Pictet [C]ompetition that my interest in IHL was awakened, and from then on, the vocational confirmation of my desire to deepen my studies in Public International Law in general and in IHL in particular”. While this idea of an “awakening” suggests that even a student who had no previous IHL affinity could have their plans shaped by Pictet, we must also note that there could be some pre-determination in these careers – that is, those predisposed to humanitarian work might be more likely to self-select to participate in the competition in the first place.

Chart 8. Responses to the question: What describes best your current field of activity?

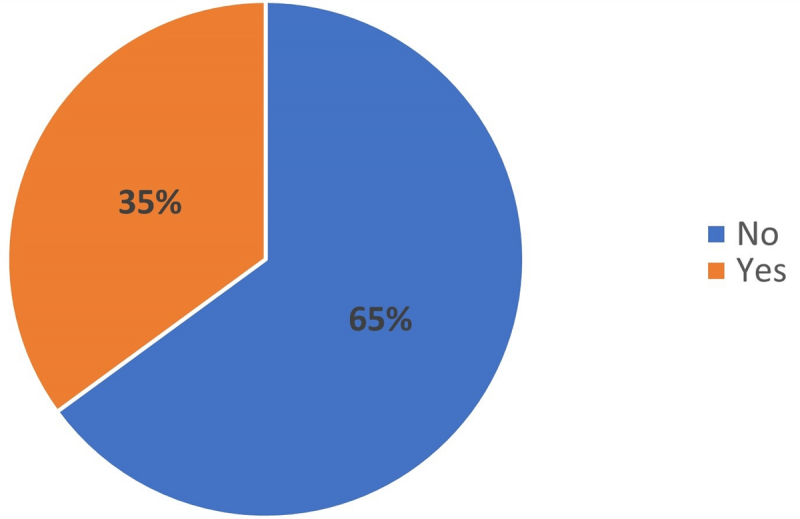

Participating in the Jean-Pictet Competition does not always lead to a humanitarian career, of course. Some 65% of survey respondents are not currently working specifically on humanitarian affairs,25 while 35% (seventy-five of the respondents) said that they had since acquired some sort of professional experience in this field (see Chart 9).

Chart 9. Responses to the question: Have you worked as a professional in the humanitarian field?,

Our survey findings suggest that one cannot trace a clear arc between Pictet participation and a future humanitarian career, yet the Jean-Pictet Competition clearly serves a role as an impactful advocate for humanitarian values, principles and ways of being in the world. The competition also promotes an engaged perspective on the function of law, encouraging participants to adopt a more human-centred approach to their own professional development. The latter could be applicable within or beyond the specific fields of IHL and humanitarianism, as participants might bring a certain kind of sensibility into future non-humanitarian roles as well.

Acquiring a humanitarian sensibility at the Jean-Pictet Competition

As we contemplate different ways of engaging with law, we are invited to consider what the Jean-Pictet Competition offers to participants more holistically – regardless of whether they pursue humanitarian careers or not. Practically speaking, survey respondents said the competition was highly influential in allowing them to develop professional skills that have contributed to success in their respective fields. In every type of legal practice (or scholarship), professionals will need to engage effectively in teamwork, cooperation and strategic thinking, and they will need to display emotional intelligence and cultural sensitivity when interacting with others.26 Our survey and our own observations of the competition suggest that this dynamic is even stronger when participants do opt for a career in IHL or humanitarianism. While there are of course many capable humanitarians in the field who have never engaged with the Jean-Pictet Competition, the formative training offered by the competition allows students to refine and develop skills that could prove useful – or indeed indispensable – when working as a humanitarian professional. Developing a humanitarian sensibility makes for better professionals in the field and, in the case of those who join armed forces or organized armed groups, might promote stricter compliance with relevant rules.27

Those attending the competition might also have the sense that student participants are “becoming humanitarian”, so to speak – that is, law students are being initiated into the wider global community of humanitarians. This does not necessarily mean being shaped in the mould of the Red Cross actor, although many Picteists would be. It is about being ready more generally to resort to a teleological interpretation of IHL, taking into account its humanitarian objective and applying it in real life with actual people who experience suffering and distress as a consequence of armed violence.28

Having highlighted the issue of professional skills and competencies, we now wish to push further and think about what it means to adopt a certain kind of sensibility about IHL and humanitarianism. Here it is important to stress that the Pictet experience does (and, indeed, needs to) go beyond a mere technical exercise. Part of what is potentially being disseminated is a way of being in or engaging with the world, a posture of approaching global problems that hopefully avoids a merely technocratic or techno-legal/managerial response. Here we are inspired by Simpson's reflections on teaching international law. Simpson notes that the teaching of PIL has increasingly come to be understood as a technical and differentiated endeavour, with separate courses on arbitration and humanitarian intervention, for example.29 The trend towards an overly technical or managerial type of training for students of international law displaces non-vocational approaches in which one seeks to understand the world for its own sake. The problem, in short, is that today's PIL classroom emphasizes “usefulness”.30 In Simpson's alternative vision, PIL would offer a final refuge for the humanities, a place where students might engage in “flights of imaginative fancy or rebellious thinking or, even, humanist pedagogy and liberal education”.31 As an aside, Simpson's observation that an international criminal law course might be encouraged to service the war on terror warns against the simplistic notion that we simply need more emotional approaches to law teaching. The potential for courses on law and war to rally emotions like caution, fear, anxiety and desire for revenge in problematic ways underscores the complexity of engaging with emotions in legal education.

One opening here is to think about the place of creativity in IHL and humanitarian work. Experienced humanitarian professionals often mention the importance of creativity in their daily engagement with IHL in the field (or in policy contexts), and it is interesting to consider how creativity might be inculcated in Pictet participants. Creativity might be engaged, for example, where they are encouraged to find novel ways of using IHL in the competition. Turning to fiction offers one way of moving beyond the merely technical, recalling Nussbaum's argument that literary experience can shape the individual reader's emotional engagement with the world.32

The above observations on processes of “becoming humanitarian” at the Jean-Pictet Competition invite us to reflect more deeply on what it means to join a community of humanitarians or humanitarian professionals. Staying close to the focus on emotions in this piece, we can think of the humanitarian community as a particular “affective community”, since those who are engaged in it share a set of common values that allow them to evaluate what surrounds them from similar perspectives. We might also consider here the concept of “circulation of affect”, related to the idea of contagion and creativity of affect. According to Ross, through the deployment of conscious and unconscious exchanges of emotions, social interactions “intensify, harmonize, and blend the emotional responses of those who participate in them”.33 The next section expands on these points, presenting the Jean-Pictet Competition as a form of interaction ritual.

Emotions and interaction ritual at the Jean-Pictet Competition

Our research findings show that Pictet participants understand that they must master legal rules and techniques in order to succeed. But also, and this is crucial, participants come away with the sense – if they did not have it prior to the competition – that their ability to grapple with their own emotions and those of others is decisive in the outcome. In light of this, we elucidate here an approach to the phenomena of interaction ritual, emotional energy, affective communities and circulation of affect, which could provide a theoretical framework to help us think of the Jean-Pictet Competition in emotional terms. Developing specific cases in which individuals “feel” the realities of armed conflict through their own experience allows for a bottom-up understanding of IHL. This perspective requires a consideration of how attention to emotional identities could complement traditional law-focused rational/abstract approaches.34

When considering the encounters of student teams adopting different identities in role-plays and simulation exercises at the Jean-Pictet Competition, it is instructive to think about the proceedings as a form of interaction ritual.35 Interaction ritual, a concept introduced by Durkheim and developed by Collins and Goffman, refers to the dynamics of all types of interaction that take place between two or more persons.36 The interaction could be as casual as a shared lunch, or as formal as a Sunday morning service in a US megachurch.37 Engaging with the theory of interaction ritual means adopting an approach that focuses on whether a successful ritual has occurred between participants in a given instance. The attention to ritual also responds to the emphasis on relationship-building that we see in various aspects of humanitarian practice (such as efforts to promote “community acceptance”), recognizing that the outcome of a discrete encounter may be less important than the process of building trust and good relations with one's interlocutors over time.

In order to have a successful ritual, Collins argues, four ingredients must be in place: the assembly of a group; barriers to exclude outsiders, whether physical (e.g. a locked building) or symbolic (e.g. legal knowledge); mutual focus of attention; and a shared emotional mood amongst participants.38 The format of the Jean-Pictet Competition amply supplies all of these ingredients, and when one observes the proceedings one has the impression that participants are indeed “caught up in the rhythm and mood of the talk”.39

What is particularly compelling about interaction ritual theory for thinking about the Jean-Pictet Competition is that it equates strong and meaningful rituals with high levels of emotion. Rather than attempting to contain or suppress emotions, a successful ritual is one that achieves high “emotional energy” – a state of well-being that follows from an interaction in which there is strong solidarity.40 An extreme variant of this is captured in Durkheim's concept of “collective effervescence”: “a sort of electricity [that] is generated from their [participants’] closeness and quickly launches them to an extraordinary height of exaltation. Every emotion expressed resonates without interference in consciousnesses that are wide open to external impressions; each one echoing the others.”41 It may be too much to expect that the Jean-Pictet Competition would offer participants an “effervescent” experience – though having personally experienced or observed the competition ourselves, we would say this is clearly within the realm of possibility – but what is instructive is Durkheim's more general insight that emotions have positive social functions that become especially apparent in rituals.42 Adept hosts and facilitators can also work to increase this emotional intensity, both in their preparation before proceedings and in the way that they navigate an event's early moments – the opening ceremony of the Jean-Pictet Competition being an obvious example.

Also crucially, Durkheim is drawing attention to collective emotions shared at the level of a community or social group which “imbue a community's socially shared beliefs and values with affective meanings, thus making these values salient in everyday, mundane interaction, well beyond the immediate ritual context”.43 Successful interaction rituals engender amongst participants a sense of solidarity, which Collins defines as “a feeling of group membership and closeness”.44 More than this, as Rossner notes in the restorative justice context, a successful interaction ritual can create “moral beings”.45 The different rituals involved in the Jean-Pictet Competition have proven to be useful in endorsing among participants the sense of belonging to a humanitarian community, one that is composed of engaged students and more seasoned professionals. When it comes to Picteists (i.e., those who have participated in the competition), the affective experience created during the week seems to play a key role in generating awareness and shaping common attitudes toward the importance of regulating war and alleviating the suffering it causes.

If we consider the different roles that Pictet participants are asked to play at the competition, it also becomes clear that there are layers of (collective) emotions to uncover. 46 Each party to a humanitarian negotiation with an armed group, for example, will belong to a group or organization, which has its own motives and values.47 Humanitarian negotiators and armed actors will share (some) emotions with their own social group – their in-group – and that social group will have its own rituals which embed their shared beliefs with affective meaning. The negotiation encounter is cast in a new light here: we now have an individual (or several) belonging to one in-group interacting with an individual (or several) belonging to another. Whether or not fellow members of one's in-group are physically present, the existence of the group and its shared system of beliefs and emotions is significant.48

This invites us to think of the negotiation encounter – as it unfolds on the front line, or in simulations at the Jean-Pictet Competition – not as a meeting of the individuals involved, so much as the collision of different “affective communities”. As conceptualized by Hutchinson, affective communities are “constituted through, and distinguished by, social, collective forms of feeling”.49 A key insight of the “affective community” concept is that emotions which appear to be individual are in fact collective as well as political.50 In this regard, “emotions are embedded in and structured by particular social systems and, as such, are interwoven with the dominant interests, values and aspirations of those systems”.51

Related phenomena which we could consider that emphasize collectivity and the affective domain include emotional climates, emotional atmospheres, inter-group emotions and circulating affects.52 These concepts offer a thorough explanation of the social dimension of group-shared experiences, which promotes, encourages and facilitates the interaction of sentimental processes.53 Since emotions extend well beyond and between persons, affective moods and feelings are easily transferred in community settings.54 Reciprocal permeation of emotional states characterizes the staging of common activities in which people are exposed to similar stimuli, and this becomes obvious in the organization of a role-playing exercise such as the Jean-Pictet Competition.

While we might productively consider individual experiences of any kind of humanitarian encounter, this discussion has conveyed that there is an undeniable collective or communal element that shapes the interaction rituals which occur at Pictet. The role of emotions needs to be acknowledged in the creation of a group identity at the competition: the Picteists become a “family”, and their belonging to the group shapes their identity as such. This collective identity is based upon a shared knowledge of IHL and, at the same time and perhaps more importantly, upon the same appraisal of the emotional involvement required for working in humanitarian environments and engaging with the world as a self-identified humanitarian.

Conclusion: What the Jean-Pictet Competition can provide in emotional terms

This article has demonstrated that in IHL learning, as in armed conflicts, emotions play an important part. A more explicit engagement with emotions has the potential to strengthen IHL training, to further IHL compliance and the development of IHL rules, and to enhance legal education more generally. As it sets up a neutral space in which participants come together to contemplate the legal regulation of armed conflicts, the Jean-Pictet Competition can not only teach participants about the negative emotions of war, but also help to translate those emotions into positive ones.

Taking into account the significant 81% IHL-career change or confirmation revealed by the survey (see Chart 7), the influence of the Jean-Pictet Competition on the academic and professional futures of student participants is beyond dispute.55 While this outcome is no accident, it is also true that the engagement with emotions at the competition to date has not been as conscious and intentional as it could be. By identifying a set of inflection points in the build-up to the competition and in the week's proceedings, the present discussion has demonstrated that there are moments in which individual and collective emotions are felt more strongly at Pictet. Those running the competition could play an important role in harnessing these moments as opportunities to intensify the emotional energy and more consciously direct it towards the formation of a humanitarian “affective community”. If participants feel pride in representing their institutions, for example, then the opening ceremony presents a chance to channel this pride into a broader conception of solidarity – initially with other Picteists, but eventually, one hopes, with populations caught up in war. Engaging carefully with “bad” emotions like stress, fear, anxiety, regret and embarrassment will also be important. Given that one of the central goals of the competition is naturally “to compete”, these difficult emotions cannot be avoided; encouraging thoughtful reflection amongst participants on how such emotions shape their experience and their engagement with IHL could be instrumental for their professional futures. Related to this, we have sought to underscore a ritualistic sociological aspect to the competition: that of cementing the Pictet group and helping them to adopt a humanitarian outlook in their respective professional paths, whatever those paths may be. The payoff of looking at the competition as a form of interaction ritual is that it draws attention to emotions and opens further opportunities to inculcate qualities such as empathy, open-mindedness and impartiality. The role-plays are particularly important here, and approaching them with an emphasis on process, rather than outcome, is essential.

In closing, we offer several recommendations for incorporating a more intentional “law and emotions” approach that can engage some of the unique features of the Jean-Pictet Competition to promote extra-legal teaching outcomes.

The theoretical framework developed in this discussion may be useful for future iterations of the competition, in which building in a more explicit emotional component to the exercises could be considered. In this sense, the Pictet works (and should continue to do so, in more explicit terms) as a laboratory in which experimenting with emotions serves to attain positive goals in controlled scenarios.56 In the field test, for example, a practical simulation exercise is drafted for students to interact with victims or other people affected by violence. Here the “kitchen” could design a scenario that tests IHL's emotional dynamics and explicitly promotes participants’ sentimental development and affective awareness. One might envision here a scenario in which the roles of “victim” and “war criminal”, or perhaps “terrorist” and “revolutionary hero”, are not clearly distinguishable. Since navigating moral ambiguity and grey areas is already an implicit part of the competition, the move here would be to foreground such challenges and to explicitly frame them as opportunities for testing the boundaries of a humanitarian sensibility.

Thinking also of Simpson's entreaty to imagine PIL as a refuge of the humanities and a non-technical endeavour, we might revisit the readings and preparation materials that students engage with in advance of the competition. In the documents prepared by the CCJP, which include useful information on IHL and also address teamwork and role-playing, space could be devoted, as Nussbaum advises,57 to engaging with fiction and literature that elucidates conundrums relevant to the humanitarian endeavour.58 This could provoke a more expansive understanding of what a relevant IHL text might be in the context of Pictet – perhaps something ultimately very different from the Geneva Conventions.

As we propose additional ways to challenge and engage Pictet participants, we should not forget that influence is travelling in multiple directions. In addition to the cross-cultural and cross-community learning that occurs, cross-generational IHL is also on offer at the Jean-Pictet Competition. When one considers the encounters that Pictet participants have with one another and with more seasoned practitioners, such as the members of the jury,59 it becomes clear that it is not only students whose lives are being shaped. In fact, the Pictet proceedings promote several layers of emotional circulation: participants can themselves influence what humanitarianism is and what it looks like as a practice, even for those who are already involved in the field. This contribution is crucial, because IHL practice sorely needs fresh thinking and creative approaches in order to keep the field relevant.

Indeed, there may be persistent modes of thought amongst humanitarians that require challenging and contestation in order to be invigorated. Consider, for example, the concepts of “humanitarian space” and the neutrality of the competition, which constitute features upon which Pictet participants are judged. Engaging with neutrality through hands-on exercises could expose a conflict that practitioners routinely grapple with, and one that students could help to inform thinking on. The clash here is potentially between the notion of a neutral humanitarian space, on the one hand, and an entreaty to embody the “spirit of IHL”, on the other. The latter might imply feeling strongly about helping humans in need or suggest being passionate about the protection of war-affected populations. As students import their own views and understandings of neutrality into the competition, their engagement might offer us new ways of conceptualizing how neutrality does, or should, implicate the commitment to IHL and its affective dimension. Limiting influence to a one-way transit from the jury to the participants would be a shame here, as it presents more a form of indoctrination rather than an invitation to reshape and reimagine the possibilities of IHL. This points to the power of thinking of Pictet as a form of interaction ritual – that is, it directs attention to how the interactions amongst student participants, and between all students and the seasoned practitioners, potentially (re-)constitute the very idea of what it means to be humanitarian. Humanitarianism is ultimately a construction in which good practices circulate, together with shared values and affective perceptions, and the Jean-Pictet Competition is an ideal environment in which to reinforce this positive “emotional contagion” and implement a true affect-based education.

There is a further contribution that law students could make within and beyond the competition, which is bringing law and humanitarianism into closer and more informed contact. Given that the average humanitarian practitioner working for the Red Cross, UN agencies and other NGOs is not typically a lawyer and is not likely to be formally trained in legal skills and argument, law students and legal practitioners are well positioned to make valuable contributions to the humanitarian community. While the present discussion focuses on shaping participants holistically as future practitioners, we are not advocating here for the law to fade away or drop off from the competition. On the contrary, identifying legal problems, advancing legal strategies and putting forward good-faith legal arguments must remain a core part of the exercise, as enshrined in the motto of the competition: “taking the law out of the books”.

Playing several roles, a landmark feature of the Jean-Pictet Competition, can also teach participants about different ways of “thinking like others” well beyond the scope of the competition. In fact, a lesson could be drawn from the Pictet simulations for the training of professional humanitarians as well as soldiers – two very different affective communities. By putting themselves in the shoes of another as part of their training, individuals can acquire some distance from their own perspective and grasp how different communities implement IHL. Swapping roles in their respective trainings might create ethical dilemmas that can produce insightful reflections on their mandates, competing expectations, and the value of dialogue.