Terrorist offences and international humanitarian law: The armed conflict exclusion clause

Introduction

A group of individuals operating from a European country collects money and recruits fighters for a non-State armed group (NSAG) that is a party to an armed conflict in the Middle East. In their home country, the individuals are prosecuted for a range of terrorist offences. In their defence, the accused submit that, as their activities relate to an armed conflict, they are excluded from prosecution for terrorist offences. How should the criminal court address such an argument?

Of course, situations of armed conflict are pre-eminently governed by international humanitarian law (IHL). At the same time, many of the activities of members of NSAGs and their affiliates in relation to armed conflicts qualify as terrorist offences under “criminal law instruments on terrorism”. The latter notion is used here to refer to international and regional legal instruments that oblige States to criminalize terrorist activities, as well as to domestic criminal law sanctioning terrorist offences. This article will look at the international sectoral terrorism conventions1 and a range of regional conventions on terrorism.2 Another relevant instrument is European Union (EU) Directive 2017/541 on combating terrorism,3 which all EU member States have implemented in their national criminal codes.4

IHL and criminal law instruments on terrorism are based on different rationales. The first section of this paper will show how their concurrent application to situations of armed conflict and related activities causes friction. One can eliminate or at least reduce this friction by clarifying whether and to what extent criminal law instruments on terrorism apply to situations of armed conflict. Indeed, some international and regional instruments contain a clause excluding activities governed by IHL from their scope of application. The second section discusses the exclusion clauses that exist at the international and regional level.

Thirdly, this article analyzes and compares some exclusion clauses in domestic criminal legislation. To our knowledge, only very few countries have adopted such clauses. Based on a literature review, they have been identified in the laws of Belgium, Canada, Ireland, New Zealand, South Africa, Switzerland and the United States.

The Belgian, Canadian and New Zealand exclusion clauses are the most encompassing. They apply not just to specific terrorist offences, but to all terrorist offences, including offences relating to (mere) participation in a terrorist group. Furthermore, their scope is not limited to a particular type of armed conflict. To better understand the practical effects of these clauses, the interesting case law from Belgium and Canada is analyzed in the fourth section.

In the penultimate section, the said case law is used to clarify the personal, material and geographical scope of application of the exclusion clause and compare it with the scope of application of IHL. The final section contains suggestions on how the exclusion clause should be applied to realize the underlying rationales of IHL and criminal law instruments on terrorism while ensuring that war criminals and terrorists are prosecuted on the basis of the appropriate legal framework.

Friction between IHL and criminal law instruments on terrorism

How IHL approaches terrorism

Combatants participating in international armed conflicts (IACs) enjoy a combatant privilege or immunity,5 meaning that criminal law instruments on terrorism cannot serve to criminalize their mere participation in hostilities. In non-international armed conflicts (NIACs), members of NSAGs fight States or fight each other without such combatant privilege. Hence, IHL does not preclude States from prosecuting acts committed by members of NSAGs, even if permitted under IHL, as terrorist offences.6 For there to be a NIAC, it is required that (1) the relevant violence is of sufficient intensity, and (2) the NSAG involved is sufficiently organized.7 The required level of organization of the group can be established by a range of indicative criteria, notably including “the existence of a command structure and disciplinary rules and mechanisms within the group” that enable it to implement IHL.8 Factors other than intensity and organization, such as the aim of the NSAG, are irrelevant.9 Thus, NSAGs designated as “terrorist” can also be a party to an armed conflict.10 Put differently, IHL deals with (alleged) terrorist groups involved in an armed conflict irrespective of the “terrorist” label.11

Furthermore, IHL addresses terrorist acts committed in the context of an armed conflict. It specifically prohibits acts of terrorism against civilians who are in the power of a party to the conflict.12 In the conduct of hostilities, “acts or threats of violence the primary purpose of which is to spread terror among the civilian population” are prohibited.13 Apart from these specific prohibitions, general IHL rules prohibit most other acts that could be classified as terrorism in peacetime, like attacking civilians or civilian objects.14 As serious violations of IHL constitute war crimes, these IHL prohibitions can – and must – be enforced through criminal law.15 On the other hand, IHL does permit certain activities that are forbidden and criminal in peacetime, like attacking combatants and military objectives.16

How the use of criminal law instruments on terrorism affects IHL

Overall, IHL provides parties to an armed conflict with a neutral code of conduct regardless of the aim they pursue.17 The notion of terrorism, on the other hand, is a “powerful rhetorical tool”18 that is “ideologically and politically loaded; pejorative; [and] implies moral, social and value judgment”.19 Hence, the aim behind acts of terrorism is what distinguishes them from other crimes20 and lies at the heart of attempts to define terrorism.21 Due to the disagreement on the definition of terrorism at the international level, the sectoral terrorism conventions generally refrain from taking into account the said aim.22 These conventions oblige States to criminalize certain types of (objective) conduct, like aircraft hijacking.23 At the regional level, States have agreed on definitions of terrorism. Accordingly, many regional instruments on terrorism do take into account the aim behind the acts they cover.24 Under EU Directive 2017/541 on combating terrorism, a number of acts, like an attack on a person's life, constitute a terrorist offence if they are committed with at least one of three aims:

(a) seriously intimidating a population;

(b) unduly compelling a government or an international organization to perform or abstain from performing any act;

(c) seriously destabilising or destroying the fundamental political, constitutional, economic or social structures of a country or an international organisation.25

Directive 2017/541 defines a “terrorist group” as “a structured group of more than two persons, established for a period of time and acting in concert to commit terrorist offences”.26

It goes without saying that an NSAG involved in an armed conflict against a State commits violent acts with at least one of the aims listed above and thus qualifies as a “terrorist group” under the Directive.27 This qualification may engender the misconception on the part of certain State authorities that “terrorist groups” cannot be a party to an armed conflict or that IHL does not apply to them.28 For example, when ratifying Additional Protocol I (AP I) and the 1980 Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons, the UK attached a reservation stating that “the term ‘armed conflict’ of itself and in its context denotes a situation of a kind which is not constituted by the commission of ordinary crimes including acts of terrorism whether concerted or in isolation”.29 Another example of this misconception is the Belgian case law on jihadist groups discussed below, in which courts have essentially denied that the relevant groups were a party to an armed conflict because they met the definition of a terrorist group.

Further friction between IHL and criminal law instruments on terrorism stems from the fact that the latter usually do not distinguish between acts permitted and acts prohibited by IHL, but criminalize both.30 This criminalization undermines the legal incentive for armed groups to comply with IHL.31 According to the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), acts permitted by IHL “constitute the very essence of armed conflict and, as such, should not be legally defined as ‘terrorist’ under another regime of law”.32 To enhance the implementation of IHL, acts prohibited by IHL should be prosecuted as war crimes and not as terrorist offences.33 Lastly, in some situations, labelling an NSAG “terrorist” may fuel or at least solidify hostility, and prejudice potential peace and reconciliation efforts.34

Considering the above, there are sound reasons to exclude activities governed by IHL from the scope of criminal law instruments on terrorism.35 That is what a number of international and regional instruments have done.

Exclusion clauses at the international and regional level

There are twelve international conventions on terrorism, two of which contain a unique provision governing their relationship with IHL that does not appear in any of the other conventions. Article 12 of the 1979 Hostages Convention provides that the Convention shall not apply to acts of hostage-taking prohibited by IHL, but only refers to those committed in IACs.36 Article 2(1)(b) of the 1999 Terrorist Financing Convention extends its definition of offences falling within the scope of that Convention to situations of armed conflict, but only for the financing of attacks against civilians or other persons hors de combat.37 Hence, the Terrorist Financing Convention does not criminalize the financing of attacks against combatants or military objectives, whether in international or non-international armed conflicts.38

Here we will focus on the “standard” exclusion clause, which has become the prevalent armed conflict exclusion clause since 1997. At the international level, this clause is included in six of the international conventions on terrorism.39 Furthermore, it is the subject of controversy in the negotiations of the Comprehensive Convention on International Terrorism.40

The clause was conceived in the context of the 1997 Terrorist Bombings Convention, and first appeared in Article 19(2) of that Convention. It is part of a two-pronged provision, and reads:

The activities of armed forces during an armed conflict, as those terms are understood under international humanitarian law, which are governed by that law, are not governed by this Convention, and the activities undertaken by military forces of a State in the exercise of their official duties, inasmuch as they are governed by other rules of international law, are not governed by this Convention.41

The second prong deals with the activities of military forces of a State in different situations, like law enforcement or peacekeeping operations not amounting to armed conflict, and is not the issue here. The first prong relates to situations of armed conflict and is the exclusion clause studied here.

The travaux préparatoires of the Terrorist Bombings Convention reveal that the provision was controversial from the outset. A number of mostly Western States primarily wanted to exclude the military activities of States from the scope of the Convention.42 A number of predominantly Muslim States, on the other hand, were troubled by the exclusion of “State terrorism”. At the same time, many of those States wanted to selectively exclude the application of the Convention to wars of national liberation,43 an approach subsequently adopted for the Organization of African Unity (OAU, now African Union (AU)), Organization of the Islamic Conference (OIC, now Organization of Islamic Cooperation) and Arab regional conventions on terrorism.44 Lastly, some States favoured an unambiguous extension of the exclusion clause to the activities of NSAGs. These States usually did so only for activities “in accordance with” IHL.45

The result of the negotiations was a relatively ambiguous clause, excluding from the scope of the Convention “activities of armed forces during an armed conflict”. In IHL instruments and parlance, the term “armed forces” is usually reserved for IACs and thus for State armed forces and, in rare situations, national liberation movements.46 The armed forces of non-State parties to a NIAC – i.e., NSAGs – are usually referred to as “organized armed groups”.47 Moreover, the debates about the exclusion clause in the context of the Terrorist Bombings Convention48 and Comprehensive Convention on International Terrorism show that some States do not consider the notion of armed forces to extend to non-State parties to a NIAC.49 Conversely, Article 3 common to the four Geneva Conventions refers to the armed forces of non-State parties to NIACs as “armed forces”. Furthermore, in light of the principle of equality of rights and obligations of the parties to an armed conflict, the ICRC believes that the exclusion clause should also cover NSAGs.50

Some have argued that since the drafters referred to “armed forces” in the first prong of the provision but to “military forces of a state” in the second prong, “armed forces” must by implication also cover non-State forces.51 However, this argument is not conclusive. The first prong is about situations governed by IHL and hence refers to “armed forces”, a notion known in IHL. The second prong is not about IHL, but is about all “other rules of international law”. Thus, the drafters opted for “military forces of a state” as a sui generis notion, which they defined separately in Article 1(4) of the Terrorist Bombings Convention.52 Both notions operate in different legal spheres, and it seems that they should not be read in relation to one another.

During the negotiations on the Comprehensive Convention on International Terrorism, in 2002, the member States of the OIC launched a competing version of the standard exclusion clause that replaces the notion “armed forces” with “parties”.53 In 1998 and 1999, the ICRC made a similar proposal during the negotiations of the Nuclear Terrorism Convention and the Terrorist Financing Convention.54 According to Pejic, the term “parties” “is correct as a matter of IHL because that is the term of art used to designate the opposing sides in an armed conflict, whether international or non-international”.55 Nevertheless, this term appears to be unacceptably broad for the States favouring the standard clause. It would extend the scope of the exclusion clause to all non-State parties to armed conflicts in their entirety, including civilians belonging to such non-State parties.56 We will assume that the standard exclusion clause also covers the armed forces of non-State parties to NIACs.

Quite clearly, the wording of the standard exclusion clause is not, or at least is no longer, accepted across regions. This explains why it is only in Europe that the clause has been copied into regional criminal law instruments on terrorism.57 It is included in the 2005 Council of Europe Convention on the Prevention of Terrorism,58 and as a recital in the 2002 EU Framework Decision on combatting terrorism59 and the 2017 Directive replacing it.60 This suggests that at least for EU member States, the exclusion clause forms part of the “acquis” of criminal law instruments on terrorism.

Some argue that nothing in IHL precludes the application of the international sectoral terrorism conventions or, for that matter, regional legal instruments on terrorism. They consider notably that the sectoral conventions’ cooperation regime, involving matters of mutual legal assistance and extradition, should also apply to activities governed by IHL.61 However, the issue is not whether IHL excludes the application of the sectoral conventions – indeed, save for the bar imposed by the combatant privilege in IACs, it does not. Rather, the issue is whether the sectoral conventions exclude their application to activities governed by IHL. As we have just shown, they do. The advocates of the said view correctly note that the Geneva Conventions and Additional Protocols provide for only a limited regime of international cooperation in relation to war crimes, namely the grave breaches regime, which exists only in IACs.62 However, as noted by Trapp, and especially in light of the friction between IHL and criminal law instruments on terrorism discussed above, “it is not … for the terrorism suppression regime to remedy gaps in IHL criminal law enforcement”.63

The fact that the sectoral conventions do not apply to activities of armed forces governed by IHL does not necessarily make this exclusion mandatory. If the exclusion clause is mandatory, States are obliged to implement it into their national criminal law and are prohibited from qualifying the activities of armed forces governed by IHL as terrorist offences. If it is not, excluding these activities from the reach of domestic criminal law on terrorism is a mere possibility, but not an obligation. In light of the role of IHL discussed above, one could argue that the exclusion clause should be mandatory;64 however, it seems that at least as a matter of law, “the exclusionary clauses are by nature options and not mandatory exceptions”.65 This is also the view adopted by the UK Supreme Court in R v. Gul66 and the Court of Justice of the EU in the LTTE case.67 As stressed by Dutch courts, this optional nature goes especially for the EU legal instruments, which include the exclusion clause only in a non-binding recital.68 Nevertheless, a few States have, in varying ways, transposed the exclusion clause into their domestic legislation.

Exclusion clauses at the national level

We will discuss States’ domestic exclusion clauses from the least to the most encompassing. We mainly differentiate between States that only have one or more “offence-specific” clauses (Switzerland, the United States and Ireland) and States that (also) have a “general” clause (South Africa, Canada, New Zealand and Belgium). Offence-specific clauses usually follow the wording of the sectoral convention or regional criminal law instrument on terrorism that they implement, and attach to one or more specific domestic terrorist offences (e.g. terrorist bombing). General clauses apply to all terrorist offences in a State's criminal legislation, including group offences like participation in the activities of a terrorist group.

Secondly, we differentiate between exclusion clauses that only cover acts “in accordance with” IHL (South Africa, Canada and New Zealand; Switzerland, the United States and Ireland for terrorist financing) and those that follow the wording of the standard exclusion clause and cover all acts “governed by” IHL (Belgium; United States and Ireland for offences other than terrorist financing). “Acts in accordance with IHL” comprise only those acts that are permitted by IHL, whereas “acts governed by IHL” include all acts that are contemplated by IHL rules, regardless of whether they comply with them or not. As they follow the wording of the standard exclusion clause, clauses covering all “acts governed by IHL” limit their personal scope of application to the activities of “armed forces” during an armed conflict. The clauses only covering “acts in accordance with IHL” do not contain a limitation on their personal scope of application.

Lastly, the South African clause is the only one that exclusively applies to wars of national liberation. The other clauses do not contain such a limitation.

Offence-specific clauses: Switzerland, the United States and Ireland

Until recently, the only terrorist offence in the Swiss Criminal Code was terrorist financing. The relevant provision states that there is no such offence if the financing is directed at acts in accordance with IHL.69 This approach corresponds to the specific provision included in the 1999 Terrorist Financing Convention. A new Swiss law (2020) now criminalizes participation in and support of a terrorist group, as well as recruitment and training for, and travel for the purposes of, a terrorist act. It does not contain any exclusion clause.70

In the United States, the standard exclusion clause is attached to the offence of acts of nuclear terrorism and that of terrorist bombings.71 The standard exclusion clause is indeed included in the 2005 Nuclear Terrorism Convention and the 1997 Terrorist Bombings Convention. The fact that the United States copied the exclusion clause from the relevant conventions when implementing them is illustrated also by the fact that the offence of terrorist financing includes the specific provision of the 1999 Terrorist Financing Convention.72 However, as noted by the UK Supreme Court in the Gul case, the position of the United States on the exclusion clause in domestic criminal law is “ambivalent”, as some of its provisions on terrorism are “widely drawn without the exclusion”.73

In Ireland, the standard exclusion clause is attached to the criminal law provision on “terrorist offences” and to the “offence of terrorist bombing”.74 Much like for the United States, this mode of implementation can be explained by Ireland's literal implementation of the relevant international and European instruments.75 Ireland also transposed the specific provisions of the 1979 Hostages Convention and the 1999 Terrorist Financing Convention into its domestic law.76 Especially, the exclusion clause attached to the provision on “terrorist offences” covers a broad range of acts. Nevertheless, this clause falls short of being general because it does not affect the definition of terrorist activity or hence, notably, the definition of a terrorist group,77 which depends on the definition of terrorist activity.

General clauses: South Africa, Canada, New Zealand and Belgium

In line with the OAU/AU – as well as the Arab and OIC – conventions, the South African clause only covers wars of national liberation. Furthermore, it only applies to acts in accordance with IHL.78

The Canadian Criminal Code's definition of “terrorist activity” provides that it “does not include an act or omission that is committed during an armed conflict and that, at the time and in the place of its commission, is in accordance with customary international law or conventional international law applicable to the conflict”.79 The Code also contains the specific provision of the 1999 Terrorist Financing Convention for the offence of terrorist financing.80

The situation in New Zealand is similar. The Terrorism Suppression Act of 200281 defines a “terrorist act” in three ways.82 First, there is a general definition, which excludes an act that “occurs in a situation of armed conflict and is, at the time and in the place that it occurs, in accordance with rules of international law applicable to the conflict”.83 Second, the definition of a terrorist act includes an “act against a specified terrorism convention”, if such an act is not excluded from the relevant convention.84 That concerns the exclusion clause. Third, the definition includes “a terrorist act in armed conflict”, which in turn comprises only attacks against civilians or other persons hors de combat, echoing the specific provision of the 1999 Terrorist Financing Convention.85

As they apply to the definition of a terrorist act or activity, both Canada and New Zealand's main exclusion clauses affect group offences like participation in terrorist groups.86 However, they do not cover group offences entirely, as in both countries, terrorist groups are defined not solely in relation to the notion of terrorist acts, but also as “listed” or “designated” entities.87 Such listing takes place in the context of “administrative” counterterrorism sanctions regimes and does not depend on “criminal” law definitions that contain the exclusion clause.88

Belgium approached the matter in a different way. It copied the exclusion clause as conceived in the context of the 1997 Terrorist Bombings Convention and later transposed in the 2002 EU Framework Decision on combating terrorism into its Criminal Code.89 The clause excludes the activities of armed forces governed by IHL completely from the application of the Code's entire chapter on terrorist offences, which includes the offence of participation in the activities of a terrorist group. The clause does so irrespective of whether the activities are in accordance with IHL or not. This is remarkable, as the proposals that Belgium submitted during the negotiations of the 1997 Terrorist Bombings Convention only excluded acts “in accordance with” IHL.90

Even if it applies only to the activities of “armed forces”, overall the Belgian clause is the broadest: it is general (not offence-specific), it covers all acts governed by IHL (not just acts in accordance with IHL), and it covers all situations of armed conflict (notably, it is not limited to wars of national liberation). The Canadian and New Zealand clauses are not limited to the activities of armed forces, but only cover acts in accordance with IHL. Canada and Belgium provide the most interesting case law on the exclusion clause, to which we now turn.

National case law

The Canadian Khawaja case

Momin Khawaja is a Canadian citizen who in 2002–04 was part of a relatively small jihadist group dubbed the “Kyam group”. This group operated from the UK and had loose links with Al-Qaeda. Khawaja was involved in the creation of a device for detonating explosives remotely (the “hi-fi digimonster”). He also travelled to Pakistan to receive training to fight in Afghanistan, but in the end never directly participated in any hostilities.91 In 2005, he was charged with a range of terrorist offences under the Canadian Criminal Code.92 The defence argued that Khawaja only wanted to participate in the armed conflict in Afghanistan, and that due to the exclusion clause, his acts fell outside the definition of terrorist activity.93 This argument was dismissed at first instance by the Ontario Superior Court of Justice, deciding per Judge Rutherford, and on appeal by the Court of Appeal for Ontario and eventually the Supreme Court of Canada.94

The courts did not qualify the armed conflict in Afghanistan. On an abstract level, Judge Rutherford took “judicial notice” of the conflict situation in Afghanistan,95 an approach accepted by the higher courts.96 The judge then held that the exclusion clause “simply had no bearing on the case”. He found that Khawaja and his affiliates were not “soldiers or part of an armed force or involved in any armed conflict or in a place where an armed conflict was underway” and that the exclusion clause “should not be extended to their non-combatant activity”.97 According to the judge, the clause is intended to cover acts which are committed in the course of an armed conflict, by those actually engaged in it.98 He also put emphasis on the geographical aspect, finding that there was no “armed conflict in Canada, the United Kingdom or in Pakistan where the acts with which Khawaja is charged, were carried out”.99 This territorial limitation is remarkable, as Canada and the UK were involved in the post-9/11 armed conflict in Afghanistan (notably against the Taliban), which first constituted an international and subsequently (from June 2002 onwards) a non-international armed conflict.100

Furthermore, Judge Rutherford held that Khawaja knew that the Kyam group “was far more than just a support mechanism for front line armed combat in accordance with the international rules of war”. Khawaja knew of the group's broader terrorist activity, which went beyond support and preparation for violent jihad in Afghanistan or elsewhere. Notably, Khawaja did not seem to care where his device(s) would be used.101

The Court of Appeal largely followed, but disagreed with Judge Rutherford's “narrow construction” of the geographical scope of the exclusion clause. It found that the accused's acts or omissions need not be carried out within the territorial limits of the armed conflict. Rather, they only have to be committed “during” an armed conflict, and be in accordance with IHL.102

Subsequently, the Court of Appeal agreed with Judge Rutherford that there was no evidence that either Khawaja or the insurgents in Afghanistan had acted in accordance with IHL. On the contrary, Khawaja's statements showed that he made no distinction between civilians and combatants and that he “supported the indiscriminate and random murder of civilians”.103 Lastly, like Judge Rutherford, the Court considered that Khawaja's actions did not solely relate to the insurgency in Afghanistan but extended beyond it.104 The Supreme Court agreed. As it put succinctly, Khawaja's “conduct cannot be said to have been taken solely in support of an armed conflict, nor was it in accordance with applicable international law”.105

Belgian case law on “jihadist” groups106

Initially, in Belgium, the exclusion clause was only invoked, yet never applied, in cases regarding individuals who had supported or joined groups that for reasons of simplicity can be called “jihadist”. The Sharia4Belgium case constitutes a representative example.107 Sharia4Belgium was a radical Islamic group based in Antwerp that recruited youngsters to join the ranks of Jabhat Al-Nusra and Majlis Shura Al-Mujahideen and fight in Syria. Forty-six individuals, nearly all of whom actually went to Syria and joined one of these two groups, were charged with participation in the activities or the direction of a terrorist group for conduct committed in Belgium and Syria from 2010 to 2014. The accused argued that because of the exclusion clause, they could not be convicted for terrorist offences.

The courts held that at no point had there been an armed conflict in Belgium, so the exclusion clause could not be invoked for activities committed by members of Sharia4Belgium in Belgium.108 Once more, given Belgium's involvement in the NIAC with the so-called Islamic State group (IS), this categorical statement is questionable.109 The courts then accepted the existence of a NIAC in Syria in abstracto, without discussing the intensity requirement or identifying the parties to this conflict.110 Subsequently, they analyzed whether Jabhat Al-Nusra and Majlis Shura Al-Mujahideen constituted armed forces in the sense of IHL and ruled that neither did.

We use the Court of Appeal's arguments about Jabhat Al-Nusra to illustrate the Belgian courts’ flawed assessment of jihadist groups. As the Court had accepted the existence of a NIAC with sufficient intensity, it had to answer the question of whether Al-Nusra was sufficiently organized to constitute an armed force or armed group in the sense of IHL. However, the Court stressed several elements that seem irrelevant to determining whether a group is sufficiently organized for the purposes of IHL or not, like the fact that there were various foreign fighters in the ranks of the group, that it regularly posted statements on jihadist forums, and that the group's leader operated under a nom de guerre.111 Furthermore, the Court stressed that Al-Nusra was responsible for almost 600 attacks (out of which thirty were suicide attacks), as well as kidnappings, hostage-takings and executions. However, while a high number of IHL violations may be indicative of a lack of organization, this is not necessarily so. As long as the armed group has the organizational ability to comply with IHL, even a pattern of IHL violations does not mean that it fails to meet the organization criterion.112 At the time, Al-Nusra was an armed group with thousands of fighters, an identified leadership, a clear strategy, a strict military organization and its own court system, and should therefore have been treated as a party to an armed conflict in Syria.113 Nevertheless, the judges held that Al-Nusra did not have a responsible command, that disciplinary rules to ensure compliance with IHL could not be enforced, and that therefore it did not constitute an armed force in the sense of IHL.114

Arguably, the courts’ reluctance to qualify Jabhat Al-Nusra and Majlis Shura Al-Mujahideen as armed forces was primarily inspired not by these groups’ (alleged) lack of organization, but rather by ideological considerations that come with the notion of terrorism.115 Not only in their assessment under the relevant criminal law provisions on terrorism but also in their assessment under IHL, both courts stressed that the groups belonged to the international terrorist network of Al-Qaeda and were waging a sectarian fight against Shia Muslims, secular people, democratic values, human rights and IHL. Furthermore, the courts stressed that the groups engaged in terrorist activities like suicide attacks that destabilized the region and created unrest among the population.116 Overall, it seems that the courts did not want to qualify the groups as armed forces because they were terrorist groups. This flies in the face of the IHL tenet that the aim of a group is irrelevant for its qualification under IHL. Nevertheless, the Court of Cassation, which is the Belgian Supreme Court, confirmed the appeals judgment.117 Forty-four individuals were convicted of participation in the activities or the direction of a terrorist group. The Sharia4Belgium case is but one illustration taken from years of jurisprudence in which Belgian courts kept ruling that the exclusion clause was inapplicable to jihadist armed groups because they were not armed forces.118

The Belgian PKK case

Belgian courts applied the exclusion clause for the first time in a case concerning alleged members of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (Partîya Karkerên Kurdistanê, PKK),119 a militant political organization mainly active in and against Turkey. Much like in the Sharia4Belgium case, forty individuals and two media companies affiliated with the Belgian branch of the PKK were charged with participation in the activities or direction of a terrorist group. The acts underlying the charges were committed in Belgium from 2004 to 2014, and consisted, for example, of organizing events to finance the PKK, recruiting members and spreading propaganda for the organization.

The courts now explicitly determined that the violence between Turkey and the PKK was of a sufficient intensity and that the PKK was sufficiently organized, and that hence there was a NIAC between the two.120 However, at first instance and during the first appeal, the courts once more mistakenly took into account the armed group's aim in order to qualify it under IHL, albeit in the opposite way from the Sharia4Belgium case. The Court of Appeal stressed that the PKK's aim is to establish an independent State, and not to terrorize the civilian population.121 The judges used this argument to disqualify the PKK as a terrorist group and to qualify it as an armed force.122

The Court's finding that the PKK does not act with a terrorist aim implies that it does not constitute a terrorist group under the Belgian Criminal Code. Consequently, mere participation in its activities is not a terrorist offence either, and one could have expected the Court to conclude that the exclusion clause did not even have to be considered. The Court did, however, apply the clause, which was a rather superfluous exercise.123 Overall, the Belgian courts’ reasoning was undermined by their failure to accept that the qualification as an armed force under IHL should not depend on the group's aim. This approach threatened to render the Belgian exclusion clause superfluous, as it could not be meaningfully applied. However, the Court of Cassation annulled (most of) the Court of Appeal's judgment for lack of motivation.124 This offered the latter – sitting in a different composition – a second chance to rule on the case.

In 2019, the Brussels Court of Appeal broke the conundrum. The Court started with the observation that the PPK could fit the Belgian Criminal Code's definition of a terrorist group. Therefore, it had to examine whether the exclusion clause applied.125 The prosecution claimed that a distinction should be made between armed forces, being those who directly participate in hostilities in a continuous way, and civilians, being those who are not members of the armed forces.126 It argued that the exclusion clause only applies to armed forces whose activities have a nexus to the armed conflict. Since the PKK affiliates standing trial were civilians and their activities had no nexus to the armed conflict, the prosecutor concluded that these activities were not governed by IHL.127 The Court disagreed. It replied that the definition of a terrorist group in Article 139 of the Belgian Criminal Code requires that the group operates to commit terrorist acts as listed in Article 137. Article 137 criminalizes as terrorist offences certain physical acts – most of them violent, such as murder – which are committed in a terrorist context and with a terrorist aim.128 The Court argued that as the acts listed in Article 137 which have been committed by the PKK have a nexus to the armed conflict and fall under the exclusion clause, the PKK is not a terrorist group in the sense of Article 139. Consequently, mere participation in its activities is not a terrorist offence.129 This time, appeal against the judgment of the Court of Appeal was rejected by the Court of Cassation.130 The case against the alleged members of the PKK was dismissed.

Like the Canadian jurisprudence in Khawaja, the Belgian PKK case raises important questions about how the scope of the exclusion clause relates to the personal, material and geographical scope of application of IHL, which we analyze in the next section.

The scope of the exclusion clause vis-à-vis the scope of IHL

Personal scope

There is no principled limitation to IHL's personal scope of application. Khawaja or the alleged members of the Belgian branch of the PKK are individually bound by, at least, the criminalized rules of IHL and can be held individually responsible for such violations provided their conduct has a nexus to the armed conflict.131 However, the personal scope of the standard exclusion clause is more limited. As stressed by the Belgian Federal Public Prosecutor's Office in the PKK case, the clause only applies to activities of members of the “armed forces”.132 While Judge Rutherford made a similar argument,133 the wording of the Canadian clause does not provide for this limitation,134 which is probably why the higher courts focused on the fact that Khawaja did not act in accordance with IHL rather than on the fact that he was not a member of any armed forces. Defendants like those in the PKK case did not directly participate in the hostilities and do not have a continuous combat function, and were hence not part of the armed forces.135 By implication, they were civilians who cannot directly benefit from the standard exclusion clause. Nevertheless, the accused in the PKK case were able to benefit from it indirectly.

Material scope

Judge Rutherford warned that the scope of the exclusion clause “should not be extended to … non-combatant activity”.136 Along the same lines, in the PKK case, the Belgian Federal Public Prosecutor's Office argued that for the exclusion clause to apply, the actual activities that are the subject of the charges (e.g., organizing events to finance the PKK) must “in concreto, objectively and effectively” be governed by IHL.137 To this argument, the Belgian Court of Cassation replied that it is “not required to determine for every concrete act of an armed force during an armed conflict that that act in concreto, objectively and effectively falls under IHL”.138 Thus, the Court seems to agree with Van Steenberghe's argument that for the purpose of the exclusion clause, IHL should be considered to govern not only direct military operations, but rather the whole of hostile activities or activities harmful to the enemy. Once it has been determined that a person is a member of the armed forces, that person's activities of assistance to an armed group, which may not be expressly permitted or prohibited by IHL (e.g., cooking or cleaning), should also be considered to be governed by IHL.139 But what about activities like collecting money for an (alleged) terrorist group, committed by civilians, as is the case here?

Many terrorist offences are “indirect”, in the sense that they may not require a link with a specific physical or “direct” terrorist offence like a terrorist murder or bombing.140 Such indirect offences include participation in the activities of a terrorist group, and other ancillary offences like the financing of terrorism.141 These offences appear to fall beyond the material scope of IHL. For example, the collection and funnelling of money by Belgian PKK affiliates for the organization can hardly be said to be governed by IHL.142 How, then, could the courts in the PKK case come to the conclusion that such activities benefit from the exclusion clause?

It is worth recalling that the exclusion clause was conceived in the context of the Terrorist Bombings Convention. At least at conception, the clause had an “offence-specific” nature and applied to a direct, physical act (“detonating an explosive or other lethal device”)143 that is typically also committed by armed forces in armed conflict. However, the Canadian Criminal Code, New Zealand Terrorism Suppression Act and EU Framework Decision on combating terrorism, as implemented into the Belgian Criminal Code, gave the exclusion clause a “general” nature. They linked it also to indirect, non-violent terrorist activity, like the behaviour encompassed by “participation in the activities of a terrorist group”.144 While the group must still act “in concert to commit [direct] terrorist offences”,145 persons participating in the activities of a terrorist group do not need to commit a physical act that would constitute a direct terrorist offence. In the PKK case, the Belgian courts reasoned that by cutting the direct connection with a physical act like a terrorist bombing, murder or kidnapping, the above instruments also no longer require the direct connection with the “activities of armed forces governed by IHL” to which the exclusion clause was intended to apply. Nevertheless, an indirect connection remains: the clause applies to the physical acts which armed forces commit in the context of an armed conflict and which are governed by IHL. This exclusion in turn affects the indirect offences.

Geographical scope

Judge Rutherford in Khawaja and the Belgian courts in Sharia4Belgium held that to the extent that the activities of the accused were committed in countries where no armed conflict was taking place, they fell outside the scope of the exclusion clause. In Khawaja, the higher courts rejected this narrow construction because the clause only requires that the activities are committed “during” an armed conflict and does not state that they have to take place within the conflict zone. The finding in Sharia4Belgium on the geographical scope was, in turn, similarly contradicted by the judgments in the PKK case, as the judges focused on where the physical acts that allegedly made the PKK a terrorist group had taken place.

The prosecution argued that the PKK had also committed terrorist offences outside the area of armed conflict. It submitted convictions of PKK members for terrorist offences from Italy, France, Denmark and Germany. The Court agreed that the geographical scope of application of IHL is limited to the territory controlled by the parties to the conflict and spillover incidents in neighbouring States.146 To the extent that acts constituting direct terrorist offences attributable to the PKK were committed in Western European countries, the PKK could in principle be qualified as a terrorist group.147 However, many foreign judgments invoked by the prosecution concerned indirect terrorist offences, such as participation in the activities of a terrorist group. The Court dismissed these judgments as irrelevant for the qualification of the PKK as a terrorist group. That qualification depends exclusively on the (intended) commission of direct terrorist offences as listed in Article 137 of the Belgian Criminal Code. Some foreign judgments did concern acts constituting such offences, like a kidnapping or attacks with Molotov cocktails. Here, the Court chiefly found that it was not established that these acts could be attributed to the PKK. Overall, it could not conclude that the PKK had committed or planned to commit acts constituting direct terrorist offences outside the area of armed conflict that delimited the geographical scope of application of IHL. Hence, it was not a terrorist group in the sense of the Belgian Criminal Code.148

Although the result seems odd, it makes sense. It is true that the Court applied the exclusion clause to persons who are not members of armed forces, and whose activities fall outside the material and geographical scope of application of IHL. However, if the main (direct) offences benefit from the application of the exclusion clause, ancillary (indirect) offences should as well.149 Even then, as implied by the findings of the Canadian courts in Khawaja and the Court of Appeal in the PKK case, there are limits to the scope of the exclusion clause.

The limits to the scope of the exclusion clause

In Khawaja, the Canadian courts held that the accused could not benefit from the exclusion clause for two reasons. First, his conduct was not in accordance with IHL. As the Belgian clause covers all activities of armed forces “governed by” IHL, this argument is irrelevant in the Belgian context.150 A second reason why Khawaja did not benefit from the clause was that his conduct and the activities of the Kyam group not only related to the armed conflict in Afghanistan, but also involved the planning of terrorist attacks outside of that context.

In the PKK case, the Court of Appeal limited the scope of the exclusion clause in a similar way, but its argumentation hinged more explicitly and exclusively on the geographical scope of application of IHL. It held that if members of the relevant armed group commit acts that constitute direct terrorist offences (also) outside the area of armed conflict, these acts, and by consequence the group, no longer benefit from the exclusion clause. It seems that the Court anticipated future cases involving armed groups, like IS, that do not limit themselves to committing violent acts within the area of an armed conflict.

The Court of Appeal's focus on the geographical scope of application of IHL in the PKK case is not without its challenges. As outlined above, Belgian courts adhere to the traditional position that in NIACs, IHL only applies to the territory controlled by the parties to the conflict and spillover incidents. Following this position, any actual terrorist acts committed outside of that area could serve to qualify the relevant armed group as a terrorist group. The ICRC would add that the geographical scope of application of IHL extends to States involved in an extraterritorial NIAC.151 As Canada was involved in an armed conflict with the Taliban, and Belgium in an armed conflict with IS, this approach would entail that acts by members of the Taliban or IS's armed forces with a nexus to the conflict committed on Canadian or Belgian territory would still benefit from the exclusion clause.152 Authors like Sassòli go further than the ICRC and argue that there is no principled limitation to the geographical scope of application of IHL in NIACs.153 IHL then applies globally, to any act that has a sufficient nexus to the conflict. Still, “conduct to be regulated must have a stronger nexus with the NIAC the further away from the NIAC it occurs”.154 If the conduct has no nexus to the armed conflict, it falls not under IHL but under the “human rights-centred ‘law enforcement’ paradigm” of which criminal law instruments on terrorism are a part.155 Assuming the relevant acts have a sufficient nexus to the conflict, the view that the geographical scope of application of IHL is in principle unrestricted largely undermines the geographical limit which the Court of Appeal set to the exclusion clause. It is unlikely that the Belgian courts would ever adopt this view.156

Where to draw the line?

IHL does not prohibit States from prosecuting activities committed by NSAGs, whether as terrorist or common criminal law offences. It seems that, at least as a matter of international law, neither does any exclusion clause. However, once States implement an exclusion clause into their domestic legislation, which we believe they should, the clause regulates the relationship between the State's domestic criminal law provisions on terrorism and IHL in a compulsory way. The clause limits the extent to which activities committed in relation to armed conflicts can constitute terrorist offences. It does not affect the possible qualification of these activities as international crimes or common criminal law offences under domestic law.

That being said, we agree with the Brussels Court of Appeal that an NSAG which exclusively commits violence in the context of an armed conflict is not a terrorist group for the purposes of criminal law instruments on terrorism.157 Due to the exclusion clause, the group's conduct should be assessed only under IHL. Acts permitted by IHL should not be prosecuted as terrorist offences. Acts prohibited by IHL should be prosecuted as war crimes or, if the conditions are met, as other international crimes like crimes against humanity or genocide. Activities of assistance committed by members of armed forces should also be considered to be governed by IHL. If they are sufficiently connected to war crimes, they can be punished as such – for example, under the mode of liability of aiding and abetting.158 Those who may not have physically committed the crime but still bear responsibility for it should not escape justice either. International criminal law uses broad forms of liability like joint criminal enterprise, co-perpetration or command responsibility. These allow prosecutors to cast a wide net and to include those who “delegate” or “outsource” the more gruesome criminal activity. Overall, this approach preserves the integrity of IHL by ensuring that the activities of NSAGs are excluded from prosecution as terrorist offences while violations of IHL are prosecuted and punished as such.159

We also agree with the Brussels Court of Appeal that if the main conduct benefits from the exclusion clause, ancillary activities cannot be qualified as terrorist offences either.160 If an armed group only commits the violent acts that could constitute direct terrorist offences in the context of an armed conflict, mere participation in the activities of this group is not a terrorist offence. Activities without a nexus to the conflict that cannot be attributed to the group, such as terrorist attacks outside the geographical area of the conflict by members of the group acting on their own, are not governed by IHL and are not exempt. If such acts are attributable to the group, we enter into a different scenario.

We agree with the Canadian courts in Khawaja and the Court of Appeal in the PKK case that the protection of the exclusion clause stops where a group commits or intends to commit violence “outside the context of armed conflict”, be it in a geographical sense (in which case the assessment depends on one's approach to the geographical scope of application of IHL), or because the acts do not have a nexus to the armed conflict, or both. First, this entails that if groups like the Kyam group or Sharia4Belgium act in concert to commit (direct) terrorist offences outside the context of armed conflict as well, they are terrorist groups. For the same reason, an NSAG like IS that is a party to an armed conflict is also a terrorist group and has a “dual nature”.161 In our opinion, this is the case for the group “as such” or “as a whole”, unless the group committing terrorist acts outside the context of armed conflict can be separated from the group only operating within that context. It remains the case that activities governed by IHL should not be assessed under criminal law instruments on terrorism, above all to prevent acts permitted under IHL from being prosecuted as terrorist offences.162 As argued above, acts prohibited by IHL should be prosecuted as war crimes rather than as terrorist offences.163

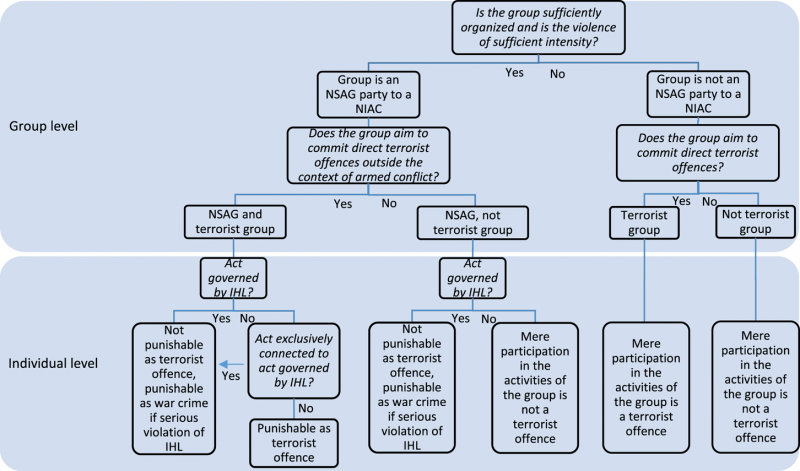

Activities, not governed by IHL, relating to groups with a dual nature can constitute terrorist offences. Notably, as they are (also) terrorist groups, the financing of and recruitment of members for such groups are (indirect) terrorist offences. There can only be an exception if the activities are exclusively connected to activities governed by IHL. If they are, and if such activities are permitted under IHL, those who contribute should not be prosecuted for terrorist offences. If they contribute exclusively to acts prohibited by IHL, these persons can be prosecuted for war crimes. A flowchart showing the application of the exclusion clause is provided in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The application of the exclusion clause.

If perpetrators have committed war crimes (or other international crimes), they should be prosecuted for those actual crimes rather than for indirect terrorist offences. As argued above, this enhances the implementation of IHL. Furthermore, “recognising and naming these crimes for what they are”164 allows courts to establish the full criminal responsibility of the perpetrators and impose tailored sentences, expose the atrocities that have been committed, and identify and engage with the victims of these crimes.165 However, in Belgium for example, the exclusion clause has unfortunately not been accompanied by an effective enforcement of IHL through the prosecution of war crimes, notably in the context of the conflict in Syria.166 As a consequence, the clause risks being perceived as precluding the prosecution of alleged terrorist offences simply because of their link with an armed conflict. This “shield” function of the clause may be particularly frustrating for prosecutors, as many indirect terrorist offences (e.g., participation in the activities of a terrorist group) are relatively easy to prove. Moreover, investigations into terrorist offences often open up a range of broader investigatory powers, which may make national criminal law on terrorism “more attractive than war crimes law as a way of dealing with terrorist offenders”.167 War crimes, on the other hand, are frequently much more difficult to prove, as they are committed on a (distant) battlefield that is inaccessible and the conditions for evidence gathering are notoriously difficult.168 Nevertheless, efforts in a number of European States in relation to the conflict in Syria show that the prosecution of war crimes is possible despite these challenging circumstances,169 if States make an additional effort (extra time, expertise, means and human resources).

Lastly, we would like to assess which clause is preferable: the standard exclusion clause, as implemented by Belgium, or the Canadian and New Zealand alternative? First, while the standard clause extends only to activities of “armed forces”, the alternative clause does not restrict its personal scope of application. Certainly, the activities of armed forces are the most important to exclude from the scope of criminal law instruments on terrorism. Nevertheless, we believe that as IHL does not limit its personal scope of application, neither should the exclusion clause. This means that civilians whose activities are governed by IHL would also benefit from the application of the clause. The requirement that the relevant conduct must have a sufficient nexus to the armed conflict, which is much less readily satisfied by civilians,170 ensures that activities which should fall under criminal law instruments on terrorism still do so. Furthermore, avoiding the term “armed forces” in the exclusion clause also avoids the ambiguity of the term that we have highlighted above.

Second, while the Belgian clause applies to all activities “governed by” IHL, the Canadian and New Zealand clauses require that activities are “in accordance with” IHL. Once more, activities in accordance with IHL are certainly the most important to exclude from the scope of criminal law instruments on terrorism. Nevertheless, this requirement risks creating confusion about whether members of NSAGs, whom IHL does not grant a right to participate in hostilities, can act “in accordance with” IHL.171 Even if it is accepted that they can, such a clause might shift the discussion to whether or not the relevant armed group complies with IHL. Strictly speaking, minor IHL violations committed by the group could suffice to argue that it should not benefit from the application of the exclusion clause.172 However, as explained above, what matters under IHL is whether the group has the organizational ability to comply with IHL. If it has the capability but does not comply, those responsible can and should be prosecuted for war crimes rather than terrorist offences.

We conclude that the scope of the exclusion clause should not be limited to activities of armed forces, like in Belgium, nor to activities in accordance with IHL, like in Canada and New Zealand. In other words, criminal law instruments on terrorism should contain an exclusion clause providing that they do not apply to activities governed by IHL.

- 1There are nineteen international legal instruments: twelve conventions and seven protocols/amendments. See UN Office of Counter-Terrorism, “International Legal Instruments”, available at: www.un.org/counterterrorism/international-legal-instruments (all internet references were accessed in August 202).

- 2For references, see below note 4.

- 3Directive (EU) 2017/541 of the European Parliament and of the Council on Combating Terrorism, 15 March 2017, replacing Council Framework Decision 2002/475/JHA and amending Council Decision 2005/671/JHA [2017] OJ L 88/6.

- 4European Commission, Report from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council Based on Article 29(1) of Directive (EU) 2017/51 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 15 March 2017 on Combating Terrorism and Replacing Council Framework Decision 2002/75/JHA and Amending Council Decision 2005/671/JHA, COM(2020) 619 final, Brussels, 30 September 2020. Barring France and Italy, all member States adopted specific legislation to transpose Directive 2017/51. However, the Commission does note several transposition issues.

- 5See Protocol Additional (I) to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, and relating to the Protection of Victims of International Armed Conflicts, 112 UNTS 3, 8 June 1977 (entered into force 7 December 1978) (AP I), Art. 43(2); Jean-Marie Henckaerts and Louise Doswald-Beck (eds), Customary International Humanitarian Law, Vol. 1: Rules, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 200 (ICRC Customary Law Study), p. 384, Rule 106, available at: https://ihl-databases.icrc.org/customary-ihl/eng/docs/v1.

- 6See, for example, Kimberley N. Trapp, “The Interaction of the International Terrorism Suppression Regime and IHL in Domestic Criminal Prosecutions: The UK Experience”, in Derek Jinks, Jackson N. Maogoto and Solon Solomon (eds), Applying International Humanitarian Law in Judicial and Quasi-Judicial Bodies, TMC Asser Press, The Hague, 2014, pp. 177–178.

- 7See, notably, International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY), The Prosecutor v. Duško Tadić, Case No. IT-94-1-A, Decision on the Defence Motion for Interlocutory Appeal on Jurisdiction (Appeals Chamber), 2 October 1995, para. 0; ICTY, The Prosecutor v. Ramush Haradinaj, Idriz Balaj and Lahi Brahimaj, Case No. IT-04-84-T, Judgment (Trial Chamber), 3 April 2008, paras 49, 60; ICTY, The Prosecutor v. Ljube Boškoski and Johan Tarčulovski, Case No. IT-04-82-T, Judgment (Trial Chamber), 10 July 2008, paras 15–205.

- 8ICTY, Haradinaj, above note 7, para. 60; see also ICTY, Boškoski, above note 7, paras 194–205.

- 9ICTY, The Prosecutor v. Fatmir Limaj, Haradin Bala and Isak Muslui, Case No. IT-03-66-T, Judgment (Trial Chamber), 30 November 2005, para. 170; confirmed by International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), Commentary on the First Geneva Convention: Convention (I) for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick in Armed Forces in the Field, 2nd ed., Geneva, 2016 (ICRC Commentary on GC I), paras 447–451, available at: https://ihl-databases.icrc.org/ihl/full/GCI-commentary.

- 10ICRC, International Humanitarian Law and the Challenges of Contemporary Armed Conflicts: Recommitting to Protection in Armed Conflict on the 70th Anniversary of the Geneva Conventions, Geneva, November 2019, pp. 58–59, available at: www.icrc.org/en/document/icrc-report-ihl-and-challenges-contemporary-ar….

- 11Marco Sassòli, International Humanitarian Law: Rules, Controversies, and Solutions to Problems Arising in Warfare, Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, 2019, p. 495.

- 12For IACs, see Geneva Convention (IV) relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War of August 1949, 75 UNTS 287 (entered into force 21 October 1950), Art. 33; for NIACs, see Protocol Additional (II) to the Geneva Conventions of August 1949, and relating to the Protection of Victims of Non-International Armed Conflicts, 15 UNTS 609, 8 June 1977 (entered into force 7 December 1978) (AP II), Art. 4(2)(d).

- 13For IACs, see AP I, Art. 51(2); for NIACs, see AP II, Art. (2); ICRC Customary Law Study, above note 5, p. 8, Rule 2; recognized as a war crime under customary IHL, see ICTY, The Prosecutor v. Stanislav Galić, Case No. IT-98-29-A, Judgment (Appeals Chamber), 30 November 2006, para. 98.

- 14See, for example, Jelena Pejic, “Armed Conflict and Terrorism: There Is a (Big) Difference”, in Ana María Salinas de Frías, Katja L. H. Samuel and Nigel D. White (eds), Counter-Terrorism: International Law and Practice, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2012, p. 175.

- 15ICRC Customary Law Study, above note 5, pp. 568–611, Rules 6–8.

- 16Ibid., respectively at p. 3, Rule 1, and p. 25, Rule 7.

- 17Elizabeth Chadwick, Self-Determination, Terrorism and the International Law of Armed Conflict, Martinus Nijhoff, The Hague, 1996, pp. 7–8.

- 18K. N. Trapp, above note 6, p. 165. See also David Anderson, “Shielding the Compass: How to Fight Terrorism without Defeating the Law”, European Human Rights Law Review, No. 3, 2013, pp. 234–235.

- 19Ben Saul, Defining Terrorism in International Law, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2006, p. 3.

- 20Ibid., pp. 7, 10–11, 27, 38–45.

- 21Erling Johannes Husabø and Ingvild Bruce, Fighting Terrorism through Multilevel Criminal Legislation: Security Council Resolution 1373, the EU Framework Decision on Combating Terrorism and their Implementation in Nordic, Dutch and German Criminal Law, Martinus Nijhoff, Leiden, 2009, p. 135.

- 22The exception is the International Convention on the Suppression of the Financing of Terrorism, 2178 UNTS 197, 9 December 1999 (entered into force 10 April 2002) (Terrorist Financing Convention), Art. 2(1)(b), on which see the main text at below note 37.

- 23B. Saul, above note 19, pp. 8, 38, 130–142.

- 24Arab Convention for the Suppression of Terrorism, 22 April 1998 (entered into force 7 May 1999), Art. 1(2)–(3); OAU Convention on the Prevention and Combating of Terrorism, 1 July 1999 (entered into force 6 December 2002), Art. 1(3) (see also the African Model Anti-Terrorism Law, Final Draft as endorsed by the 17th Ordinary Session of the Assembly of the African Union, Malabo, 30 June–1 July 2011, Art. 4(xxxix)); Convention of the Organisation of the Islamic Conference on Combating International Terrorism, 1 July 1999 (entered into force 7 November 2002), Art. 1(2)–(3); Shanghai Cooperation Organization Convention on Combating Terrorism, Separatism and Extremism, 15 June 2001 (entered into force 29 March 2003), Art. 1; Additional Protocol to the SAARC Regional Convention on Suppression of Terrorism, 6 January 2002 (entered into force 12 January 2006), Art. 4(1). Some regional instruments define terrorist offences only by reference to the international sectoral conventions; see Inter-American Convention against Terrorism, 3 June 2002 (entered into force 6 July 2003), Art. 2; ASEAN Convention on Counter Terrorism, 13 January 2007 (entered into force 27 May 2011), Art. 2, but see Art. IX(1); Council of Europe Convention on the Prevention of Terrorism, 16 May 2005 (entered into force 1 June 2007), Art. 1(1), as supplemented by the Additional Protocol to the Convention, 22 October 2015 (entered into force 1 July 2017). See B. Saul, above note 19, pp. 142–168.

- 25Directive (EU) 2017/541, above note 3, Art. 3(2). Note that the EU Framework Decision of 13 June 2002 on Combating Terrorism, now Directive 2017/541, also states that the offence must involve acts “which, given their nature or context, may seriously damage a country or an international organization”. Some EU member States, such as Belgium, have interpreted this as an extra requirement for the offence. However, as Borgers points out, it is not clear whether the Framework Decision actually requires this, as the said phrase can also be read as a mere statement rather than an additional requirement. See Matthias Borgers, “Een gevaarzettingsvereiste voor terroristische misdrijven?”, in Toine Spapens, Marc Groenhuijsen and Tijs Kooijmans (eds), Universalis: Liber Amicorum Cyrille Fijnaut, Intersentia, Brussels, 2011. Therefore, other States, such as the Netherlands, have not included this phrase in their national legislation implementing the EU Framework Decision/Directive.

- 26Directive (EU) 2017/541, above note 3, Art. 2(3).

- 27See, for example, Antonio Coco, “The Mark of Cain: The Crime of Terrorism in Times of Armed Conflict as Interpreted by the Court of Appeal of England and Wales in R v. Mohammed Gul”, Journal of International Criminal Justice, Vol. 11, No. 2, 2013, p. 438.

- 28ICRC, above note 10, pp. 58–59.

- 29See: www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2001/2559/schedules/made/data.xht?view=snip….

- 30There are some exceptions to this; see the Terrorist Financing Convention, Art. 2(1)(b), and the Canadian, New Zealand, South African and Swiss exclusion clauses, as discussed below.

- 31ICRC, International Humanitarian Law and the Challenges of Contemporary Armed Conflicts, EN IC/11/5.1.2, Geneva, October 2011 (ICRC Challenges Report 2011), pp. 48–50; ICRC, International Humanitarian Law and the Challenges of Contemporary Armed Conflicts, EN 32IC/15/11, Geneva, October 2015 (ICRC Challenges Report 2015), pp. 17–18; ICRC, above note 10, p. 58; J. Pejic, above note 14, pp. 172, 184–186. See also A. Coco, above note 27, pp. 438–440; Tristan Ferraro, “Interaction and Overlap between Counter-Terrorism Legislation and International Humanitarian Law”, in Proceedings of the 17th Bruges Colloquium: Terrorism, Counter-Terrorism and International Humanitarian Law, 20–21 October 2016, p. 29; Daniel O'Donnell, “International Treaties against Terrorism and the Use of Terrorism during Armed Conflict and by Armed Forces”, International Review of the Red Cross, Vol. 88, No. 864, 2006, p. 868; B. Saul, above note 19, pp. 88, 7–8; Ben Saul, “The Legal Death of Rebellion: Counterterrorism Laws and the Shrinking Legal Freedom of Violent Political Resistance”, in Benjamin J. Goold and Liora Lazarus (eds), Security and Human Rights, Hart Publishing, Oxford, 2019, pp. 324, 337–338; Marco Sassòli, “Terrorism and War”, Journal of International Criminal Justice, Vol. 4, No. 5, 2006, p. 970; M. Sassòli, above note 11, pp. 277, 467, 597; K. N. Trapp, above note 6, p. 170.

- 32ICRC Challenges Report 2015, above note 31, p. 18; see also ICRC Challenges Report 2011, above note 31, p. 50; T. Ferraro, above note 31, p. 30; J. Pejic, above note 14, p. 177.

- 33ICRC Challenges Report 2011, above note 31, p. 51; J. Pejic, above note 14, pp. 185, 198.

- 34ICRC Challenges Report 2011, above note 31, p. 51; ICRC Challenges Report 2015, above note 31, p. 18; UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), Counter-Terrorism in the International Law Context, Advance Copy, Vienna, 2021, p. 107, available at: www.unodc.org/pdf/terrorism/CTLTC_CT_in_the_Intl_Law_Context_1_Advance_…; Andrea Bianchi and Yasmin Naqvi, International Humanitarian Law and Terrorism, Hart Publishing, Oxford, 2011, p. 163; T. Ferraro, above note 31, p. 29; J. Pejic, above note 14, pp. 196–198; B. Saul, above note 31, p. 338; K. N. Trapp, above note 6, p. 180.

- 35Also “exclusively humanitarian activities carried out by impartial humanitarian organizations operating in accordance with IHL” should be excluded from the scope of criminal law instruments on terrorism: see ICRC, “Counter-Terrorism Measures Must Not Restrict Impartial Humanitarian Organizations from Delivering Aid”, statement to United Nations Security Council debate “Threats to International Peace and Security Caused by Terrorist Acts: International Cooperation in Combating Terrorism 20 Years after the Adoption of Resolution 1373 (2001)”, 12 January 2021, available at: www.icrc.org/en/document/counter-terrorism-measures-must-not-restrict-i…; as well as ICRC Challenges Report 2011, above note 31, pp. 51–53; ICRC Challenges Report 2015, above note 31, pp. 20–21; ICRC, above note 10, pp. 59–61. However, the “standard” exclusion clause, as discussed below, is limited to the “activities of armed forces”. Also irrespective of this limitation on the personal scope of application of the standard exclusion clause, the above-mentioned humanitarian activities may not always (directly) benefit from the exclusion clauses that we discuss here. Hence, they should be the subject of a separate, so-called “humanitarian exemption” clause, e.g. Directive (EU) 2017/541, above note 3, Recital 38. On this topic, see, for example, David McKeever, “International Humanitarian Law and Counter-Terrorism: Fundamental Values, Conflicting Obligations”, International and Comparative Law Quarterly, Vol. 69, No. 1, 2020.

- 36International Convention against the Taking of Hostages, 1316 UNTS 205, 17 December 1979 (entered into force 3 June 1983) (Hostages Convention).

- 37Terrorist Financing Convention, Art. 2(1)(b).

- 38J. Pejic, above note 14, p. 188.

- 39In chronological order: (1) Convention for the Suppression of Unlawful Seizure of Aircraft, 860 UNTS 105, 16 December 1970 (entered into force 14 October 1971), Art. 3bis (2) (as introduced by Art. VI of the Protocol Supplementary to the Convention for the Suppression of Unlawful Seizure of Aircraft, ICAO Doc. 9959, 10 September 2010 (entered into force 1 January 2018)); (2) Convention on the Physical Protection of Nuclear Material, 1456 UNTS 101, 26 October 1979 (entered into force 8 February 1987), Art. 2(4)(b) (as replaced by Art. 1(A) of the Amendment to the Convention on the Physical Protection of Nuclear Material, UNTS Reg. No. 24631, 8 July 2005 (entered into force 8 May 2016)); (3) Convention for the Suppression of Unlawful Acts against the Safety of Maritime Navigation, 1678 UNTS 201, 10 March 1988 (entered into force 1 March 1992), Art. 2bis (2) (as introduced by Art. 3 of the Protocol to the Convention for the Suppression of Unlawful Acts against the Safety of Maritime Navigation, IMO Doc. LEG/CONF.15/21, 14 October 2005 (entered into force 28 October 2010)); (4) International Convention for the Suppression of Terrorist Bombings, 2149 UNTS 256, 15 December 1997 (entered into force 23 May 2001) (Terrorist Bombings Convention), Art. 19(2); (5) International Convention for the Suppression of Acts of Nuclear Terrorism, 2445 UNTS 89, 13 April 2005 (entered into force 7 July 2007) (Nuclear Terrorism Convention), Art. 4(2); (6) Convention on the Suppression of Unlawful Acts Relating to International Civil Aviation, ICAO Doc. 9960, 10 September 2010 (entered into force 1 July 2018), Art. 6(2).

- 40See Report of the Ad Hoc Committee Established by General Assembly Resolution 51/210 of 17 December 1996, UN Doc. A/68/37, 8–12 April 2013, Annex II –III, pp. 15–27.

- 41Terrorist Bombings Convention, Art. 19(2).

- 42See, for example, Report of the Ad Hoc Committee Established by General Assembly Resolution 51/210 of 17 December 1996, UN Doc. A/52/37, 31 March 1997, Annex II, Art. 3(1), and Annex IV, pp. 53–55.

- 43Most vocal were Pakistan (see, for example, Report of the Ad Hoc Committee, above note 42, Annex III, UN Doc. A/AC.252/1997/WP.16; UN General Assembly, Sixth Commitee, Pakistan: Proposed Amendments to the Draft Resolution Proposed by Costa Rica (A/C.6/52/L.13), UN Doc. A/C.6/52/L.19, 18 November 1997) and the Syrian Arab Republic (see, for example, UN General Assembly, Sixth Committee, Measures to Eliminate International Terrorism: Report of the Working Group, UN Doc. A/C.6/52/L.3, 10 October 1997, Annex II, UN Doc. A/C.6/52/WG.1/CRP.4).

- 44See Arab Convention for the Suppression of Terrorism, Art. 2(a); OAU Convention on the Prevention and Combating of Terrorism, Art. 3(1) (see also the African Model Anti-Terrorism Law, above note 24, Art. 4(xl)(b)); Convention of the Organisation of the Islamic Conference on Combating International Terrorism, Art. 2(a).

- 45See, notably, the Belgian proposals: UN General Assembly, Sixth Committee, Report of the Working Group, above note 43, Annex II, UN Docs A/C.6/52/WG.1/CRP.11, A/C.6/52/WG.1/CRP.29, A/C.6/52/WG.1/CRP.39. See also the proposal by South Africa and Switzerland: ibid., UN Doc. A/C.6/52/WG.1/CRP.27.

- 46See AP I, Art. 43; ICRC Customary Law Study, above note 5, p. 14, Rule 4; Mahmoud Hmoud, “Negotiating the Draft Comprehensive Convention on International Terrorism: Major Bones of Contention”, Journal of International Criminal Justice, Vol. 4, No. 5, 2006, p. 1036; E. J. Husabø and I. Bruce, above note 21, pp. 381–383.

- 47See AP II, Art. 1(1), on NIACs “in the territory of a High Contracting Party between its armed forces and dissident armed forces or other organized armed groups” (emphasis added), as stressed by the Court of First Instance of The Hague, The Prosecutor v. Imane B. et al., Case No. 09/842489-14 etc., ECLI:NL:RBDHA:2015:14365 (in Dutch) and ECLI:NL:RBDHA:2015:16102 (English translation), 10 December 2015 (Context case), paras 7.38, 7.40.

- 48See, for example, Report of the Ad Hoc Committee, above note 42, Annex IV, pp. 53–55.

- 49See, for example, Report of the Ad Hoc Committee Established by General Assembly Resolution 51/210 of 17 December 1996, UN Doc. A/62/37, 5–15 February 2007, p. 7; cf. Helen Duffy, The “War on Terror” and the Framework of International Law, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2015, pp. 35–36, 43–44; J. Pejic, above note 14, p. 189.

- 50UN General Assembly, Sixth Committee, Working Group Established Pursuant to General Assembly Resolution 51/210, Statement by the ICRC, UN Doc. A/C.6/53/WG.1/INF/1, 6 October 1998, fn. 3. For a similar view, see UNODC, above note 34, p. 104; Sandra Krähenmann, “Legal Framework Addressing Terrorism and Counter-Terrorism”, Proceedings of the 17th Bruges Colloquium: Terrorism, Counter-Terrorism and International Humanitarian Law, 20–21 October 2016, p. 21; D. O'Donnell, above note 31, p. 866; J. Pejic, above note 14, pp. 189–193, 203; K. N. Trapp, above note 6, p. 173. Cf. UK Supreme Court (UKSC), R v. Gul (Appellant), Case No. UKSC 2012/0124, Neutral Citation No. [2013] UKSC 64, 23 October 2013, para. 52.

- 51See, for example, A. Coco, above note 27, p. 434; Tom Ruys and Sebastiaan Van Severen, “Art. 141bis Sw. – Vervolging tussen hamer en aambeeld van terreurbestrijding en internationaal humanitair recht”, Rechtskundig Weekblad, Vol. 82, No. 14, 2018, p. 531.

- 52“‘Military forces of a State’ means the armed forces of a State which are organized, trained and equipped under its internal law for the primary purpose of national defence or security and persons acting in support of those armed forces who are under their formal command, control and responsibility.” See, for example, Report of the Ad Hoc Committee, above note 40, Annex III, p. 25, para. 27.

- 53Report of the Ad Hoc Committee established by General Assembly resolution 51/210 of 17 December 1996, UN Doc. A/57/37, 11 February 2002, Annex IV, p. 17.

- 54Ad Hoc Committee Established by General Assembly Resolution 51/210 of 17 December 1996, Replies Given on 22 March 1999 by the Observer of the International Committee of the Red Cross to the Questions Asked by the Delegations of Belgium and Mexico Regarding the Implications of Article 2, Paragraph 1(b), UN Doc. A/AC.252/1999/INF/2, 26 March 1999, p. 3.

- 55J. Pejic, above note 14, p. 192; see also p. 203. See also T. Ferraro, above note 31, p. 30.

- 56Cf. Nils Melzer, Interpretive Guidance on the Notion of Direct Participation in Hostilities under International Humanitarian Law, ICRC, Geneva, 2009, pp. 31–35.

- 57A slight exception is Art. 4(xl)(c) of the African Model Anti-Terrorism Law, above note 24, which contains a variation of the exclusion clause. The provision unambiguously excludes from its definition of “terrorist act” “acts covered by international humanitarian law, committed in the course of an international or non-international conflict by government forces or members of organized armed groups”.

- 58Council of Europe Convention on the Prevention of Terrorism, Art. 26(5).

- 59EU Framework Decision on Combating Terrorism, above note 25, Recital 11.

- 60Directive (EU) 2017/541, above note 3, Recital 37.

- 61Alejandro Sánchez Frías, “Bringing Terrorists to Justice in the Context of Armed Conflict: Interaction between International Humanitarian Law and the UN Conventions against Terrorism”, Israel Law Review, Vol. 53, No. 1, 2020, pp. 88–89, 98; Dan E. Stigall and Christopher L. Blakesley, “Non-State Armed Groups and the Role of Transnational Criminal Law During Armed Conflicts”, George Washington International Law Review, Vol. 48, No. 1, 2015, pp. 34–42.

- 62A. Sánchez Frías, above note 61, pp. 84–88; D. E. Stigall and C. L. Blakesley, above note 61, p. 39. For the grave breaches regime, see Geneva Convention I, Arts 49–50; Geneva Convention II, Arts 50–51; Geneva Convention III, Arts 129–130; Geneva Convention IV, Arts 146–147; AP I, Arts 85–89. As noted by K. N. Trapp, above note 6, p. 178, AP II does not create a criminal law enforcement regime for IHL violations in NIACs, precisely because it “leaves States free to criminalise any and all conduct during the course of a NIAC, including attacks against military objectives”.

- 63K. N. Trapp, above note 6, pp. 174–175; see also p. 181.

- 64See, for example, A. Coco, above note 27, pp. 431–435, 439–440; K. N. Trapp, above note 6, pp. 172–181.