Counterterrorism, sanctions and financial access challenges: Course corrections to safeguard humanitarian action

2021 marked the 20th anniversary of the 9/11 attacks, the seminal event spurring the creation of a global counterterrorism (CT) regime. Through the adoption of UN Security Council (UNSC) Resolution 1373,1 the strengthening of UNSC Resolution 12672 sanctions on Al-Qaeda and the Taliban, and other measures such as the UN General Assembly's 2006 Global Counter-Terrorism Strategy, an expansive international CT architecture has been established, with unprecedented obligations on UN member States to enact legislation and implement measures to combat terrorism. As responding to the attacks and preventing future terrorist threats was the primary objective in 2001, little forethought was given to the potential unintended consequences of these extraordinary CT measures. Two decades later, however, the effects of far-reaching CT measures on human rights and humanitarian action have been illuminated through multitudes of reports by civil society organizations and the UN's Special Rapporteurs.3

As other articles in this issue of the Review discuss, concerns over the impact of sanctions and CT measures on humanitarian action have escalated significantly in recent years. Groups providing humanitarian assistance in countries subject to sanctions or where designated entities operate (e.g., Syria, Iraq, Yemen, Somalia, Nigeria, Pakistan, Afghanistan) have detailed how broad CT measures restrict their ability to deliver impartial humanitarian assistance. In fact, an unprecedented number of reports4 are available describing the difficulties that humanitarian and other non-profit organizations (NPOs)5 experience while operating in regions of armed conflict, subject to sanctions, or where groups designated as “terrorists” operate.

While the reasons vary, most humanitarian actors attribute many problems to the impact of CT/sanctions measures on their ability to deliver impartial humanitarian assistance. Inadvertently providing support to designated entities could result in criminal penalties and the inability to access financial mechanisms to transfer funds to affected jurisdictions. For example, substantial delays and denials of wire transfers, account closures, and the inability to open bank accounts pose obstacles in getting assistance to populations in need. Fearful of running afoul of regulatory and due diligence requirements related to terrorism financing and sanctions, many financial institutions (FIs) have been reluctant to provide banking services to humanitarian groups operating in high-risk regions, a phenomena referred to as “de-risking”.6 In providing essential services for NPOs working internationally, banks are subject to extensive regulatory compliance requirements and must exercise enhanced due diligence on their charitable customers and international transactions to ensure that they do not facilitate terrorist activity.

Concomitant with rising concerns over the harmful effects of sanctions and CT policies on the delivery of humanitarian aid, the need for life-saving assistance has reached unprecedented levels. In December 2021, the UN Office for Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) estimated that 274 million people will need humanitarian assistance and protection in 2022. This number is a significant increase from 235 million people a year ago, which was already the highest figure in decades.7 In Afghanistan, nearly 23 million people (or 55% of the Afghan population) are estimated to be in crisis or food insecure, while 20 million people in Ethiopia are targeted for humanitarian assistance, including 7 million who are directly affected by the conflict in the north of the country.8 The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated the already perilous situation of vulnerable populations. Most of the countries identified as being in need of assistance and protection are in areas of armed conflict, to which international humanitarian law (IHL) applies.

During a UNSC General Debate in July 2021,9 Deputy Secretary-General Amina Mohammed warned of the “hurricane of humanitarian crises” taking place around the world. With the sheer scale of humanitarian needs being greater than ever before, she urged that CT measures should include clear provisions to preserve humanitarian space, minimize the impact on humanitarian operations, and ensure that humanitarian and health-care personnel are not punished for doing their jobs.10

This article provides an overview of the interplay between UN CT measures and sanctions and humanitarian action.11 The mandatory requirements of UNSC Resolutions 1267 and 1373 on member States to prohibit the provision of “funds, financial assets or economic resources”12 to terrorists creates challenges for humanitarian actors working in areas where groups designated under the 1267 regime operate. Noting the impact of sanctions and CT measures on humanitarian action, especially the chilling effects, the article explores three challenges encountered by humanitarian actors: lack of legal protection, financial access problems, and donor conditions. Humanitarian carve-outs – exceptions as employed in the Somalia sanctions regime and case-by-case exemptions utilized in the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK) regime – are analyzed, with exceptions being the optimal solution for humanitarian actors. Financial institutions, concerned for regulatory requirements to counter terrorism financing, are reluctant to provide banking services to NPOs working in highly sanctioned jurisdictions and often choose to de-risk, causing significant problems for humanitarian organizations needing to move funds to areas of conflict. The article presents new data, including from a Yale report,13 indicating that the scope and scale of financial access difficulties experienced by NPOs have grown. Conditions related to CT compliance by donors have also proven problematic for NPOs, resulting in an offloading of risk onto recipients without appropriate clarity and guidance by donors. Initiatives attempting to address the challenges that humanitarians face have expanded in recent years: stakeholder dialogues, high-level meetings and other discussion fora have promoted broader understanding and acknowledgement of the challenges posed by CT measures on humanitarian action, but concrete measures tackling these problems are still lacking. Of significance, however, is the opportunity to address humanitarian concerns through reform of the 1267 regime, as its mandate must be renewed before the end of 2021. Recommendations are presented for each of the three sets of challenges, with an urgent call for the UNSC to embrace the opportunity for reform of the current system and to establish a balance between the critical objectives of countering terrorism and safeguarding humanitarian action.

Overview of UN sanctions, counterterrorism measures and impacts on humanitarian action

Concerns about the impact of sanctions on humanitarian action are not new: the UN has long recognized the potential of sanctions to affect the delivery of humanitarian assistance and the need to protect humanitarian activities.

Sanctions adopted by the UNSC in 1968 (under UNSC Resolution 253) on Southern Rhodesia contained language exempting “supplies intended strictly for medical purposes, educational equipment and material for use in schools and other educational institutions, publications, news material and, in special humanitarian circumstances, food-stuffs” from the Chapter VII embargo.14 Humanitarian measures were also included in the comprehensive sanctions imposed by the UNSC on the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (Serbia and Montenegro), Haiti and Iraq, which contained language exempting “supplies intended strictly for medical purposes, and, in humanitarian circumstances, foodstuffs”.15

Controversy surrounding the humanitarian consequences of sanctions on Iraq, however, prompted the UN's transformational shift away from comprehensive sanctions toward targeted measures. The primary factor driving this evolution was the outcry concerning the impact of sanctions on innocent Iraqis (including reports of “hundreds of thousands” of children who had died as a result of sanctions).16 With growing concerns that broad economic sanctions caused disproportional harm, the UNSC deliberately shifted to “targeted” or “smart” sanctions as a means of focusing measures on those decision-makers responsible for violations of international norms, and their principal supporters. Underlying the shift to targeted sanctions is the assumption that asset freezes and travel bans focused on leaders would not affect the general population. All UN sanctions since 1994 have been, in some manner, targeted.17

With the end of the Cold War, the UN began imposing sanctions with greater regularity, leading the 1990s to be characterized as the “sanctions decade”.18 From 1992 to 1999, targeted UN sanctions focused on conflicts within States, seeking to prevent or reduce armed violence, promote peace and reconciliation processes, or protect human rights, especially in African conflicts (Somalia, Liberia, Angola, Rwanda, Sudan and Sierra Leone). In addition, UN sanctions were also imposed on Libya and Sudan (for terrorism) and Haiti (for restoration of democratically elected leaders).

UNSC Resolutions 1267 and 1373

In response to the 1998 bombings of US embassies in East Africa, the UNSC imposed sanctions on the Taliban and Al-Qaeda and associated groups in order to thwart international terrorism. Following the Taliban's refusal to turn over Osama bin Laden for prosecution and its hosting of training and sanctuary for international terrorist groups, the Council adopted Resolution 126719 in October 1999, consisting of assets freezes and an aviation ban on the Taliban. The measures were adopted under Chapter VII of the UN Charter, making them binding on all member States under international law.

The terrorist attacks on 11 September 2001 represent an inflection point in the evolution of UN sanctions. The significantly expanded 1267 sanctions, along with the creation of the Counter-Terrorism Committee pursuant to UNSC Resolution 1373, placed new emphasis on stemming the financing of terrorism through the adoption of domestic legislation and implementation measures by member States. These two regimes form the bedrock of the UN's CT architecture and have had the most consequential impact on humanitarian actors.

As the terrorist threat evolved, the Council adapted the 1267 regime. The measures (an arms embargo, travel ban and asset freeze) were expanded to individuals and entities associated with Al-Qaeda, and in 2015 to the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (ISIL). As such, the 1267/1989/2253 list of targeted individuals/entities is unique in its global rather than national or regional focus on non-State actors. The 1267 sanctions are also primarily preventative in nature in order to constrain targets from gaining access to essential resources (funds, people, commodities etc.), whereas other UN sanctions are principally coercive and designed to change behaviour.

Over time, the UNSC has modified the 1267 measures through more than a dozen successive resolutions, including adoption of exemptions for living expenses or travel for designated individuals.20 In 2011, UNSC Resolutions 1988 and 1989 split the regime in two, establishing one committee for the Taliban (Resolution 1988)21 and another for Al-Qaeda and affiliated groups (Resolution 1989,22 continuing other 1267 sanctions); this permitted the Council to address the specific situation related to the Taliban in Afghanistan. In addition, in 2009 the Council established an independent and impartial ombudsperson (UNSC Resolution 1904)23 to whom 1267-designated individuals may directly appeal their designation and request de-listing. While some of these changes were a result of external pressures (especially as legal challenges by designated individuals grew in Europe), the 1267 sanctions regime has demonstrated institutional development and an ability to evolve over its two decades of existence.

There are two aspects of 1267 sanctions that pose the greatest challenge for humanitarian actors. Firstly, the designation of groups subject to 1267 sanctions is of concern, especially those “terrorist” entities that control territory or have a significant presence in areas where humanitarian assistance is required. Eighty-nine entities are included on the 1267 list, having a presence or operating in more than fifty States.24 Secondly, the extraordinarily expansive definition of the asset freeze prohibition in 1267 (“funds, financial assets or economic resources”) is so broad as to encompass most conceivable activity. The Al-Qaida Sanctions Committee's explanation of terms states:

Economic resources should be understood to include assets of every kind, whether tangible or intangible, movable or immovable, actual or potential, which potentially may be used to obtain funds, goods or services, such as:

a. land, buildings or other real estate;

b. equipment, including computers, computer software, tools, and machinery;

c. office furniture, fittings and fixtures and other items of a fixed nature;

…

l. any other assets.25

UNSC Resolution 2368 further clarifies the obligation for member States

to prevent [their] citizens from making funds, financial assets or economic resources or financial or other related services available, directly or indirectly, for the benefit of terrorist organizations or individual terrorists for any purpose, including but not limited to recruitment, training, or travel, even in the absence of a link to a specific terrorist act.26

Given the scope of activity prohibited, it is understandable that NPOs providing programmes and services in areas in which designated entities operate are fearful of violating sanctions.

Of greatest significance for humanitarian NPOs, however, is the fact that there is no exception for humanitarian organizations from the prohibition on funds, assets and economic resources in successive 1267 resolutions. While paragraph 22 of Resolution 2368 calls on member States to “protect non-profit organizations, from terrorist abuse, using a risk-based approach, while working to mitigate the impact on legitimate activities”, there is no safeguard for humanitarian action from the broad scope of CT sanctions.27

UNSC Resolution 1373, adopted in response to the 9/11 terrorist attacks, operates alongside the 1267 sanctions. Adopted on 28 September 2001 under Chapter VII of the UN Charter, it represents the foundation of the current global CT regime, requiring member States to prevent the financing of terrorist acts and to criminalize the wilful provision of funds for terrorist acts.

While the 1267 regime is targeted at individuals and entities listed by the 1267 committee, there is no 1373 list (designations are at national discretion); however, the broadly worded measures and far-reaching language in Resolution 1373 pose significant challenges for humanitarian actors working in areas in which designated groups operate or which they control. Prohibitions on “making any funds, financial assets or economic resources or financial or other related services available”28 have been implemented by member States in order to preclude “material support” to terrorist groups, leaving NPOs fearful that activities permissible under IHL could be illegal under CT measures.29

Impacts on humanitarian actors and activities

The concerns of NPOs have grown increasingly consequential in the past five years with the escalation of conflict and humanitarian crises in Syria, Yemen, Afghanistan and Somalia, among other countries where designated groups operate or control territory, or where one or more of the parties to conflict are designated entities. Experiences of humanitarian actors have been cited and documented, including impacts of sanctions and CT measures on principled humanitarian action. In some cases, impartial humanitarian organizations have been prevented from carrying out their activities in a manner consistent with IHL, leaving populations in situations of increased vulnerability and undermining principled humanitarian action. In other instances, humanitarian organizations fear that activities and possible diversion of benefits to sanctioned entities may expose them and their staff to criminal prosecution or penalties, possibility resulting in liability, reputational harm and loss of funding.

Numerous reports30 note how sanctions and CT measures impact humanitarian action, both directly and indirectly, including by:

-

limiting or preventing principled humanitarian action;

-

criminalizing humanitarian action, including medical assistance;

-

restricting access of financial services for humanitarian operations; and

-

constraining the ability of humanitarian actors to engage with groups and persons permitted under IHL.

The “chilling effect” resulting from the complex regulatory framework related to 1267 sanctions and CT measures is the most oft-cited concern of NPOs. These requirements have multifaceted impacts on their organizations, limiting their ability to “implement programmes according to needs alone, and oblig[ing] them to avoid groups and agendas”, especially those areas controlled by groups designated by the 1267 regime, which the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) estimates includes more than 60 million people.31 Fear of running afoul of requirements – national laws and regulations, conditions by donor agencies, and policies of private sector actors – related to sanctions and CT measures has led some humanitarian actors to be overly cautious, at times choosing to limit their activities beyond what is required. Financial institutions, reluctant to transfer funds into higher-risk jurisdictions where humanitarian actors frequently operate, have closed bank accounts of NPOs or denied and/or delayed financial transfers. Some humanitarian groups complain that programmatic decisions have come to be based on where banks will transfer funds to, rather than solely on basis of need. NPOs report the termination of programmes in areas where designated groups have a significant presence, resulting in populations and persons entitled to humanitarian assistance under IHL being denied critical aid. Humanitarian actors have also witnessed increasing conditions and funding restrictions in the form of donors’ contractual clauses in grant agreements, which have the effect of offloading risk onto NPOs. The following section explores these challenges in greater depth.

In response to such concerns and in recognition of the consequences of sanctions and CT measures on humanitarian action, the UNSC included provisions related to compliance with IHL in UNSC Resolution 2462, a consolidated resolution aimed at combating and criminalizing the financing of terrorism. Paragraph 5 calls for domestic law and regulations to be “consistent with obligations under international law, including international humanitarian law”; paragraph 6 “[d]emands that Member States ensure that all measures taken to counter terrorism, including measures taken to counter the financing of terrorism …, comply with their obligations under international law, including international humanitarian law”; and paragraph 24 “[u]rges States, when designing and applying measures to counter the financing of terrorism, to take into account the potential effect of those measures on exclusively humanitarian activities, including medical activities, that are carried out by impartial humanitarian actors in a manner consistent with international humanitarian law”.32

The inclusion of this language was welcomed by NPOs as positive step.33 Resolution 2462 fell short, however, of providing forward-leaning measures to more fully protect humanitarian space; in particular, humanitarians advocated for explicit recognition that IHL permits impartial humanitarian organizations to offer their services to parties to armed conflict, irrespective of the latter's designation as terrorists.34 Inclusion of IHL-related language concerning allowable activities beyond providing food and medicine – such as repairing systems for water supply and sanitation, building medical facilities or clearing mines – would have protected humanitarian space more directly. The fact that clarifying language has not been adopted by the UNSC perpetuates debates about the role of IHL in CT contexts. As noted by the Special Rapporteur on the Promotion and Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms while Countering Terrorism,

these statements of principle are not sufficient to actively protect the integrity of humanitarian action and actors working in areas where terrorist groups are active. Indeed, humanitarian law already protects engagement for humanitarian purposes …. It is unacceptable for Member States and the United Nations to allow the present lack of clarity to persist and interfere with the delivery of humanitarian assistance and medical care.35

Specific challenges encountered by humanitarian actors

This section elaborates three primary sets of challenges faced by humanitarian groups in relation to UN sanctions and CT measures. The first is the lack of clarity and adequate legal protection for carrying out humanitarian activities in countries subject to sanctions or areas in which designated entities operate. The second are financial access or de-risking problems limiting the ability of NPOs to transfer funds to higher-risk regions due to FIs’ over-compliance with sanctions or fear of regulatory scrutiny for such transactions. The third are donor conditions and the offloading of risk by funders of humanitarian services onto NPOs and beneficiaries through contractual clauses related to CT and sanctions requirements.

Lack of legal protection – humanitarian “carve-outs”

As noted, comprehensive sanctions imposed by the UNSC previously included language acknowledging humanitarian impacts and protecting humanitarian activities to varying degrees. As the UN shifted in the 1990s to imposing only targeted measures on individuals and entities, sanctions committees adopted special procedures for listed individuals to apply for permission to access their frozen assets for specific purposes. These exemptions for basic or extraordinary expenses (such as rent, food, medicine or travel for judicial proceedings or religious reasons) became routine aspects of sanctions regimes, adopted by the 1267 (Al-Qaeda/ISIL), Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Sudan, Libya, Guinea-Bissau, Central African Republic (CAR), Mali, Yemen and South Sudan sanctions committees. While referred to as “humanitarian exemptions”, these measures for individuals do not relate to the provision of impartial humanitarian assistance. Rather, humanitarian “carve-outs” apply to impartial humanitarian organizations and actors conducting principled humanitarian activities. There remains significant confusion, however, concerning humanitarian exception/exemption terminology.

For purposes of clarity, this article refers to two types of provisions currently utilized by the UNSC to address humanitarian concerns: exceptions and exemptions provided for humanitarian actors to operate in sanctioned jurisdictions under certain conditions. As detailed below, a humanitarian exception exists in the Somalia regime, which excludes or excepts a specific category of actors/activities from the financial prohibitions. Instituted in 2010, this has been a critically important measure that permits humanitarian groups to provide services, especially food aid, in order to address the Somalian famine. A humanitarian exception “carves out legal space for humanitarian actors, activities, or goods within sanctions measures without any prior approval needed”.36 Humanitarian exemptions utilized in the DPRK sanctions regime, however, also authorize humanitarian activities or projects, but on a case-by-case basis whereby the sanctions committee must approve the requests of member States or NPOs. Humanitarian exemptions have been authorized in the Yemen sanctions regime, but do not appear to have been implemented.37

Humanitarian actors have advocated consistently for the inclusion of humanitarian safeguards to mitigate the impact of CT measures and sanctions. In a statement before the 11 July 2021 UNSC meeting on “Protection of Civilians in Armed Conflict: Preserving Humanitarian Space”, Robert Mardini, director-general of the ICRC, called on the UNSC to adopt well-crafted standing humanitarian exemptions and to require member States to develop specific measures to facilitate the work of impartial humanitarian organizations and carve out similar protections in domestic sanctions regimes.38

The Somalia exception

The humanitarian exception to UN sanctions on Somalia was first introduced in 2010 in response to the dire famine resulting from environmental disasters (including floods, cyclones and unprecedented desert locust swarms) and persistent conflict. Somalia has consistently hosted one of the largest humanitarian operations in the world, but because there was no exception to sanctions at the time, assistance was suspended since it was not possible for humanitarian groups to operate in areas controlled by the Islamist insurgent terrorist group Al-Shabaab without some benefits (such as road tolls, taxes or stolen goods) accruing to it.

Paragraph 5 of UNSC Resolution 1916 notes that the Council

[d]ecides that for a period of twelve months from the date of this resolution, and without prejudice to humanitarian assistance programmes conducted elsewhere, the obligations imposed on Member States in paragraph 3 of resolution 1844 (2008) shall not apply to the payment of funds, other financial assets or economic resources necessary to ensure the timely delivery of urgently needed humanitarian assistance in Somalia, by the United Nations, its specialized agencies or programmes, humanitarian organizations having observer status with the United Nations General Assembly that provide humanitarian assistance, or their implementing partners, and decides to review the effects of this paragraph every 120 days based on all available information, including the report of the Humanitarian Aid Coordinator submitted under paragraph 11 below.39

All subsequent UNSC resolutions reauthorizing the Somalia sanctions have continued the exception, which excepts or excludes from the financial sanctions a range of humanitarian organizations and activities under the UN umbrella. UNSC Resolution 255140 further bolstered humanitarian access by extending the exception indefinitely rather than limiting it to twelve months with annual renewal. Some humanitarian actors have hesitated to rely upon the exception, however, often preferring to implement programmes that operate solely in government-held areas of Somalia in order to minimize potential penalties should they inadvertently provide support to designated entities.41

Still, the importance of the UN exception in the Somalia regime cannot be overstated. The exception seems to have worked well in facilitating the provision of humanitarian assistance to Somalia and is broadly supported by member States. In fact, in 2019 a proposal was made to move Al-Shabaab from being listed in the Somalia regime to the 1267 list based on its affiliation with Al-Qaeda. A critical mass of UNSC members opposed the transfer,42 primarily because of the anticipated impact on humanitarian assistance should the group fall under 1267 sanctions: with no humanitarian carve-out in 1267, NPOs would be unable to continue to provide assistance in Somalia. Based on conversations between the author and representatives of various member States, this proposal is likely to be tabled again as Kenya is on the UNSC in 2021–22.

The Somalia carve-out has become the preferred model of NPOs where humanitarian assistance is desperately needed but is inaccessible because of sanctions.43 As recognition of the problems experienced by humanitarian organizations due to sanctions and CT measures grows, NPOs have called for similar Somalia-type exceptions to be replicated in other sanctions regimes.

The DPRK exemption

The DPRK sanctions regime under UNSC Resolution 171844 represents the other extant approach to authorizing humanitarian assistance in a sanctioned country. IHL currently does not apply to the DPRK, and as such, proliferation sanctions are outside the scope of this issue of the Review. Still, since the experience of the DPRK exemption is illustrative, it is included and analyzed here.

UNSC Resolution 2397 includes language stating that sanctions are not intended to have adverse humanitarian consequences and authorizing the committee to exempt any activity from sanctions on a case-by-case basis:

[Resolution 2397 reaffirms] that the measures imposed [by this and other UNSC resolutions] are not intended to have adverse humanitarian consequences for the civilian population of the DPRK or to affect negatively or restrict those activities, including economic activities and cooperation, food aid and humanitarian assistance, that are not prohibited …, and the work of international and non-governmental organizations carrying out assistance and relief activities in the DPRK for the benefit of the civilian population of the DPRK, stresses the DPRK's primary responsibility and need to fully provide for the livelihood needs of people in the DPRK, and decides that the Committee may, on a case-by-case basis, exempt any activity from the measures imposed by these resolutions if the committee determines that such an exemption is necessary to facilitate the work of such organizations in the DPRK or for any other purpose consistent with the objectives of these resolutions.45

It establishes a process whereby member States, international organizations and NPOs may request an exemption from the sanctions committee to facilitate the delivery of humanitarian assistance or relief activities in the DPRK for the benefit of the civilian population on a case-by-case basis.46 In addition, the committee created “Implementation Assistance Notice No. 7: Guidelines for Obtaining Exemptions to Deliver Humanitarian Assistance to the Democratic People's Republic of Korea” in 2018, which was updated on 30 November 2020.47 The committee also maintains a list of current exemptions approved on its website. As of 3 November 2021, the committee had approved a total of eighty-three humanitarian exemption requests, with twenty-one that appear to be in effect. UN agencies (the World Food Programme, UNICEF and UNFPA) have eight of the current exemptions, member States ten (with six for the Republic of Korea), and NPOs three.48

The implementation of the exemption process has been slow and problematic, however. As the humanitarian situation in the DPRK has deteriorated, the Panel of Experts for the DPRK sanctions has consistently included reports about the impacts of sanctions:

Despite the exemption clauses and the Committee's efforts, United Nations agencies and humanitarian organizations continue to experience unintended consequences on their humanitarian programmes that make it impossible to operate normally in the Democratic People's Republic of Korea. The six main areas of concern communicated to the Panel are: delays in receiving exemptions; the collapse of the banking channel; delays in customs clearance; a decrease in willing foreign suppliers; the increased cost of humanitarian-related items and operations; and diminished funding for operations. These are negatively affecting their ability to implement humanitarian-related programmes. In particular, the sectoral sanctions are affecting the delivery of a number of humanitarian-sensitive items.49

The Panel has advanced numerous recommendations to mitigate the potential adverse impacts of sanctions on the civilian population of the DPRK and on humanitarian aid operations. These include expediting the processing of exemption requests, publishing a white list of certain non-sensitive items used in humanitarian operations, requesting the Secretariat to carry out an assessment of the humanitarian impact of sanctions in the DPRK, and noting the importance of arrangements for re-establishing the banking channel.50

It is important to note that the DPRK exemption is not a broad carve-out for humanitarian groups, as in Somalia. Each request must be approved by the fifteen committee members, which requires time for review, approval (and reapplication) of requests, and for the Committee Exemption Approval Letter to be prepared. The fact that exemptions often take months to be approved and are granted for a period of only nine months has been problematic for NPOs as they strive to deal with urgent humanitarian needs. Moreover, UNSC members may have national interests within a sanctioned jurisdiction and may thus be inclined to block the approval of exemption requests; concerns for some member States’ predisposition against exemptions and use of approvals for political purposes also persist.51

The DPRK exemption model, therefore, fails to provide a consistent, reliable and readily accessible path for humanitarian NPOs: the process remains complex, bureaucratic, time-consuming, too limited, and costly in financial and human resources. While the exemptions framework allows for humanitarian assistance, the process itself is neither fit for purpose nor does it encourage or adequately facilitate such action.

For these reasons, broad exceptions for categories of approved activity or other semi-automatic approvals, instead of a case-by-case process, is necessary for an effective humanitarian carve-out process. As noted previously, the exception employed in the Somalia sanctions regime has proven effective and is thus preferred by NPOs. As recommended by several Special Rapporteurs, “[h]umanitarian actions unambiguously should be exempted from UN counter-terrorism measures”.52

Bank de-risking and financial access challenges53

Mandatory UN CT and sanctions measures, as well as soft-law standards of the Financial Action Task Force (FATF)54 related to anti-money laundering (AML), countering the financing of terrorism (CFT) and sanctions, must be transposed by UN member States into laws, regulations and policies at the national level. These regulatory measures impose compliance obligations on all stakeholders – businesses, FIs and NPOs alike. Banks that provide essential services for humanitarian and other non-profit organizations, for the purpose of conducting their activities internationally, are subject to extensive compliance requirements to exercise due diligence on their customers and transactions in order to ensure that they do not facilitate terrorist activity. Since humanitarian actors frequently operate in conflict areas, many FIs are reluctant to handle NPO accounts, engaging in risk-averse behaviour known as de-risking. While the drivers of de-risking are complex and include commercial profitability and reputational concerns, CT/sanctions issues play an outsized role in financial access restrictions.55

Humanitarian organizations are viewed as especially high-risk customers, in large part due to the FATF's adoption of Special Recommendation 8 in 2001.56 Notwithstanding repeated guidance from the FATF and revision of Recommendation 8 in 2016 emphasizing that the standard applies to a subset of NPOs only, as well as official pronouncements that de-risking is inconsistent with a risk-based approach, NPOs continue to face significant financial access challenges.

Financial institutions may choose not to service NPO clients out of concern for regulatory risk and the negative consequences of being involved in transactions to higher-risk jurisdictions. As US sanctions violations are “strict liability” offenses – that is, a person can be liable for committing a civil violation of sanctions regardless of their knowledge or degree of fault – FIs engage in complicated risk calculations about the repercussions of being found to have violated sanctions. Banks face substantial penalties related to any transactions with individuals or entities designated under a sanctions regime and can be fined for a perceived lack of effective control over the end location and use of funds, even without an actual breach of sanctions. Consequences beyond legal action and penalties include compliance costs related to mitigating violations and reputational damage; this is in addition to the fact that NPO accounts usually are not highly profitable and are more costly because of enhanced due diligence. This calculus often leads FIs to conclude that NPOs are to be avoided. Even for banks maintaining NPO clients, additional due diligence requirements associated with such accounts frequently result in delays or other problems for NPOs trying to transfer funds. These problems have increased in recent years as FIs are less inclined to hold and transfer NPO funds since it is simpler to avoid, rather than manage and mitigate, the risks associated with charitable clients.

Financial access challenges can have dramatic effects for NPOs, at times leading to the cancellation of programmes, increased costs, and substantial delays for financial transactions and, by extension, in the delivery of aid. These impacts endanger the provision of timely, effective and necessary humanitarian assistance. NPOs report that financial access difficulties also discourage support from other private sector entities necessary in delivering humanitarian assistance (e.g., medicine or goods manufacturers, suppliers, and transportation and insurance companies), resulting in delays and/or increased costs.

To overcome such problems, NPOs have resorted to other, often informal transfer methods such as carrying cash, using hawala, and money service businesses (see the following data section for greater details). While informal value transfer systems are efficient and less costly ways of moving funds, such methods can increase risks for NPOs and lead to de-risking by FIs. Of greatest concern is the fact that the use of unregulated, informal systems and cash runs counter to AML/CFT objectives of transparency and traceability and can increase the risk of diversion.

Data indicative of de-risking/financial access challenges

Until relatively recently, there have been scant data available regarding financial access problems faced by NPOs. The present author's 2017 report, Financial Access for US Nonprofits,57 based on a random sample survey of US NPOs, was the first empirical analysis of the scope and scale of de-risking. The study found that a significant proportion (two thirds) of NPOs conducting international work experienced obstacles in accessing financial services, constituting a serious and systemic challenge for the continued delivery of vital humanitarian and development assistance. The most common problems NPOs faced include delays of wire transfers (37%), unusual documentation requests (26%) and increased fees (33%). Account closures or refusal to open accounts were experienced by 16% of NPOs surveyed, and over 15% of NPOs encountered these financial problems constantly or regularly, with another 31% reporting occasional problems. Of significant concern, the data indicated that 42% of NPOs resort to carrying or sending cash when traditional banking channels become unavailable.

In 2018, the Charity Finance Group surveyed UK NPOs and released its report, Impact of Money Laundering and Counterterrorism Regulations on Charities.58 Overall, the study found that nearly four fifths (79%) of respondents experienced problems in accessing or using mainstream banking channels.

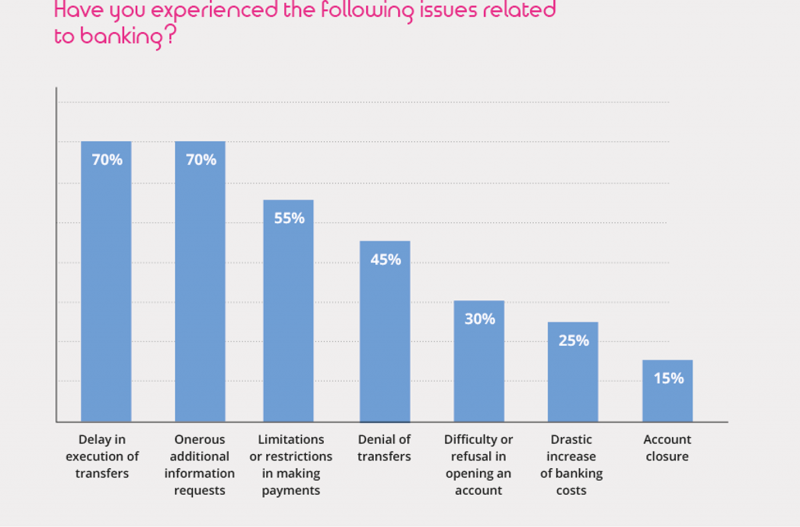

The Dutch gender platform WO=MEN and the Human Security Collective (HSC) produced the study Protecting Us by Tying Our Hands: Impact of Measures to Counter Terrorism Financing on Dutch NGO's Working on Women's Human Rights and Gender Equality (WO=MEN/HSC Study) in 2019.59 It found that 70% of NPOs surveyed had fund transfers delayed, and 45% had transfers denied (see Figure 1).

In autumn of 2020, a team of Yale University undergraduates working on a capstone project supervised by the present author developed and deployed a survey of NPOs to investigate current challenges faced in the delivery of humanitarian assistance abroad. This survey served to update data from the 2017 Financial Access for US Nonprofits study and queried new areas. The results are presented in the January 2021 report, A Data-Based Approach for Understanding the Impact of AML/CFT/Sanctions on the Delivery of Aid: The Perspective of Nonprofit Organizations (Yale Study).60

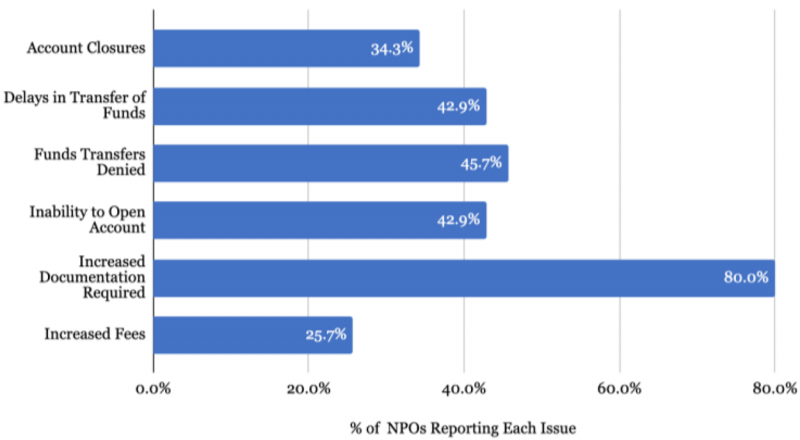

Overall, the Yale Study found that while the general percentage of NPOs experiencing financial access challenges has remained consistent (approximately two thirds of surveyed NPOs), the frequency with which NPOs experience these problems – frequently or constantly – has nearly tripled since 2017. Moreover, the challenges encountered have also increased, with multiple problems being experienced by more than 40% of respondents (delays and denials of fund transfers, inability to open accounts or account closures, and increased documentation requests – see Figure 2), indicating a broader range of financial access problems than previously found in 2017.

Figure 2. Financial access issues encountered by NPOs (2021). Source: Yale Study, above note 4.

The 2021 data suggest that while the overall percentage of NPOs facing problems may not have increased, NPOs facing problems are encountering a broader range of difficulties than previously indicated.

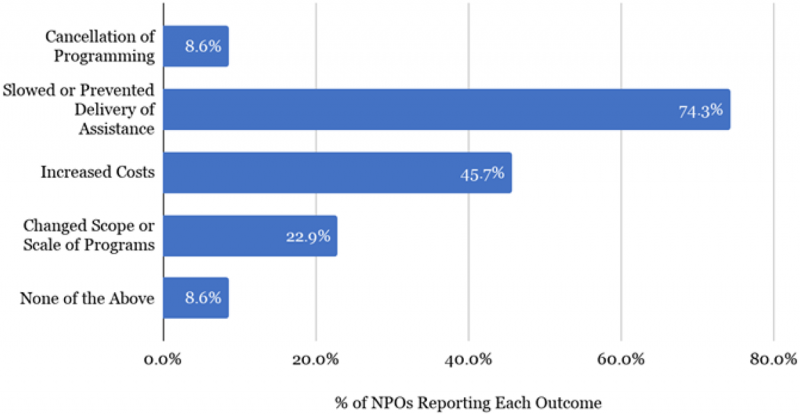

The most common result of financial access difficulties noted was slowed or prevented delivery of assistance (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Impact of limited financial access on NPOs. Source: Yale Study, above note 4.

The data reveal that CT/sanctions measures problematize and, in some cases, prevent the provision of timely services due to delays or denials of transfers by FIs. This impact is felt most directly by the intended programme beneficiaries. Most frequently, assistance is delayed or prevented, costs increase, or the NPOs are forced to change the scope or scale of their programmes. Some NPOs reported that because of financial challenges, programmatic decisions are being made based on where they can transfer funds instead of based on humanitarian need.

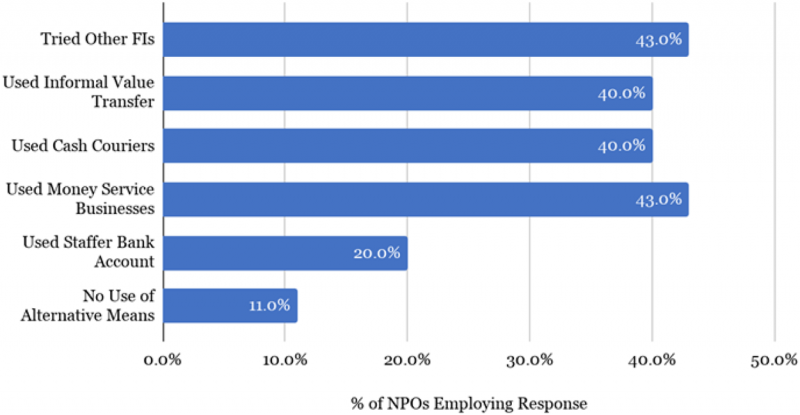

Some NPOs were able to resolve issues with their FIs, but for those with chronic financial access problems, there is a need to find alternative ways to move funds. NPOs by and large have a “can do” attitude and find “work-arounds” when faced with obstacles. 89% of NPOs indicating financial access problems utilized alternative means to move funds, such as carrying cash and using informal value transfer systems such as hawala, similar to the 2017 survey, which reported a figure of about 90%. From the perspective of security and CT objectives, these findings are troublesome since informal transfer methods are risky and less transparent, making it more difficult to monitor financial flows.

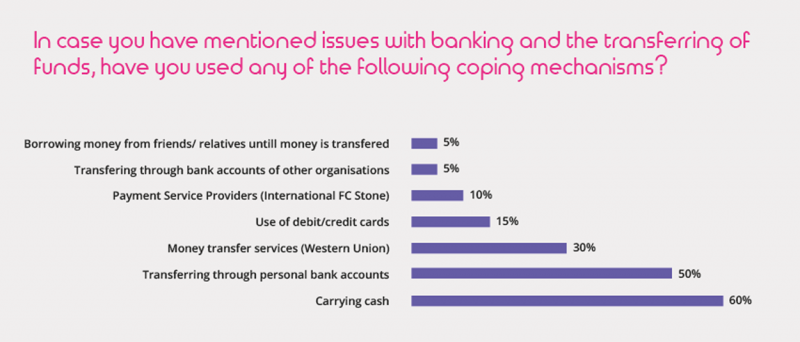

While the 2021 Yale Study (see Figure 4) recorded about the same level (40%) of NPOs using cash as the 2017 and 2018 studies, the 2019 WO=MEN/HSC Study (see Figure 5) indicated that 60% of respondents resorted to carrying cash, which is riskier and more dangerous for NPOs. In addition, the 2019 survey reported that 50% of respondents used personal bank accounts to transfer funds, in order to avoid problems associated with enhanced scrutiny of NPOs’ accounts.

Figure 4. Responses of NPOs to financial access challenges (2021). Source: Yale Study, above note 4.

Figure 5. Responses of NPOs to financial access challenges (2019). Source: WO=MEN/HSC Study, above note 55.

Overall, the data demonstrate that NPOs face serious and systemic financial access difficulties, which have grown in scope and scale over the past several years. When NPOs encounter difficulties in using the formal financial system to move funds, they revert to alternative methods that are less transparent, traceable and safe. The data speak to the need, both for humanitarian and CT objectives, to alter current practices in order to better facilitate NPOs’ access to secure financial services. While sanctions and CT measures are not solely to blame, they are currently a significant factor in FIs’ relationships with NPOs and willingness to support humanitarian transfers. De-risking and financial access for NPOs constitute a critical challenge impeding humanitarian action that will not be resolved without concerted action by all stakeholders.

Donor conditions and offloading of risk61

NPOs increasingly report that CT- or sanctions-related clauses in donor contracts constitute additional challenges for their activities. In providing funding to humanitarian actors, donors are routinely requiring greater assurances from recipients.62 In a recent case, a humanitarian organization reported that it had to forego an €800,000 grant from a European country for activities in Syria because of donor requirements which restricted activities in areas controlled by listed 1267 groups.

The UN Special Rapporteur on the Promotion and Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms while Countering Terrorism commented on this issue, writing that “donors now frequently include counterterrorism clauses in humanitarian grant and partnership agreement contracts, requiring NPOs to provide onerous guarantees that their funds are not used to benefit terrorists or to support acts of terrorism”.63 Clarifying or negotiating such clauses can delay the delivery of humanitarian assistance, as they may require engagement with the donor regarding the interpretation of contractual clauses. A Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) survey noted that 71% of respondents faced increased compliance and administrative burdens as a result of donor provisions; interviewees felt that vetting and due diligence requirements caused delays in implementation and an increase in costs.64

According to the Counterterrorism and Humanitarian Engagement Project, “[t]he general purpose of these clauses is to help ensure that donors’ funds are not used to benefit terrorists or to support acts of terrorism”.65 Donating entities, especially those affiliated with a government, need to ensure that they do not run afoul of their government's own laws. If an NPO is found to have supported designated terrorists, the funding organization and its staff may face criminal penalties. To manage and mitigate risks associated with providing funds for humanitarian organizations’ work in higher-risk jurisdictions, donors require recipients to agree to prevent the diversion of funds to designated entities or affiliates.

Donor conditions data

To better understand the degree to which donor requirements affect the operations of humanitarian groups, the Yale Study asked a series of questions. 74% of respondents reported the inclusion of CT-related clauses in donor funding agreements, with 77% of those indicating that these clauses had become more onerous over the past three years.66 A March 2021 study by VOICE also reported that 85% of the donors funding members’ activities in certain countries require clauses relating to sanctions and CT measures in their funding agreements.67

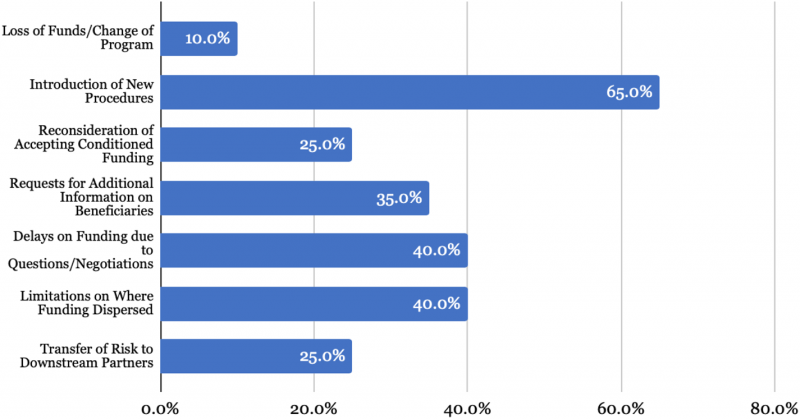

In terms of impacts of donor conditions, more than 80% of respondents to the Yale Study reported that donor contractual clauses had affected their organization noticeably or significantly. The most frequently cited result was the introduction of new procedures, followed by funding delays, limits on areas where funds could be dispersed, and the transfer of risks to downstream partners (see Figure 6). The data demonstrate that donor contractual clauses related to CT are indeed widespread and impactful, and that they have grown consequential for NPOs in recent years.

Figure 6. Impact of donor clauses. Source: Yale Study, above note 4.

Overall, donor conditions contribute to difficulties that the humanitarian sector faces by shifting risks from donors to recipients, requiring extra due diligence by NPOs, distorting relations between large and small humanitarian groups, and promoting an environment of risk intolerance or avoidance. CT measures also appear to disadvantage smaller NPOs. The 2017 report Tightening the Purse Strings: What Countering Terrorism Financing Costs Gender Equality and Security noted that CT requirements make giving directly to grassroots organizations more difficult, as these organizations are viewed as less able to manage risks in sanctioned countries or where designated entities operate.68

Moreover, humanitarian organizations consider CT/sanctions requirements to be lacking in clarity, specificity and consistency.69 Uncertainty regarding these provisions and related donor requirements increases operational difficulties for NPOs, potentially leading to over-compliance. Some NPOs have even decided to forego government funds out of concern for liability and costs associated with such conditions. While some donors have provided unwritten assurances that NPOs will not be held liable for violations if proper risk mitigation measures are taken, NPOs report that, notwithstanding such assurances, auditors reviewing cases years later have held NPOs to account for violations.70 Even with the best of intentions, donors’ efforts to reassure recipients have failed to alleviate humanitarians’ concerns regarding such conditions.

Offloading of risk

Overall, there is a strong view in the NPO community that donors are seeking to avoid risk-sharing via contractual clauses. InterAction has noted that “[m]any [international NPOs] interviewed observed that their national NPO partners are exposed to high levels of risk, often without support or training”.71 Humanitarian organizations deliver assistance and manage all the attendant risks while donors frequently offer neither guidance nor support. Evidencing this sentiment, one respondent to the Yale Study wrote that the NPO sector should push risks back to other stakeholders: “NPOs should not be the only ones taking on the risks, they should be shared.” Another asked for “greater risk-sharing between contracting agency and contractor/implementing partner”.72

In many donor contracts, the risk burden on humanitarian actors is explicit and represents a wholesale offloading of risk onto NPOs. For example, the UK Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) grant template73 includes language stating that “the Partner is solely accountable for compliance with the provisions of this Arrangement including where the Partner engages any Downstream Partners”. This clause explicitly places the burden to ensure compliance on the recipient and fails to detail any obligations of support by the donor. The document further states that “the Partner will manage all risks in relation to this project unless otherwise agreed as part of the risk register and in writing with the Fund Manager”. This provision demonstrates the default position that recipients must manage risks without donor support. The reality may be more nuanced, but the example reaffirms perceptions that donors seek to offload risks onto NPOs and generally do not appear to be interested in risk-sharing. To address these concerns, the FCDO is engaged with NPOs in developing a new template for CT language for grant agreements, calling for more reasonable steps, increasing the use of comfort letters to support humanitarian projects, and streamlining due diligence requirements.74

Donors disagree with NPOs’ contention that there is no risk-sharing, pointing to efforts to increase communications with smaller NPOs about risks and mitigation approaches. Some donors now consider the extra costs incurred by NPOs for risk management; the US Agency for International Development (USAID) allows for the inclusion of negotiated indirect cost rate agreements as part of approved reimbursable expenses under grants. NPO risk management efforts, especially the development of organizational principles, can be categorized as an indirect cost, providing an example of donor support for covering some of the costs associated with NPOs’ risk management efforts.75

In response to NPO concerns about excessive screening requirements, the Directorate-General for European Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid Operations (DG ECHO) has, as of 2021, included new provisions in its grant agreements that explicitly exclude the vetting of final beneficiaries. The language states:

The need to ensure the respect for EU restrictive measures must not … impede the effective delivery of humanitarian assistance to persons in need in accordance with the humanitarian principles and international humanitarian law. Persons in need must therefore not be vetted.76

All other individuals and entities – staff, partners, suppliers – will continue to be required to be screened.77

Finally, donor conditions pose dilemmas for NPOs by potentially conflicting with fundamental humanitarian principles of providing assistance based on need, irrespective of whether someone is a designated entity. CT provisions prohibiting interaction with certain individuals or groups or requiring screening of beneficiaries are inconsistent with humanitarian actors’ obligations under IHL. As one NPO noted, donor requirements often prohibit “direct or indirect contact” with designated groups – but in certain areas, it may be impossible to access populations in need without risk of interaction with a designated group. To avoid conflicts between IHL principles and donor obligations, some humanitarian organizations choose to discontinue operations, leaving needy people without assistance.78

Complications arising from donor conditions in funding agreements79

USAID requires each of its award recipients to sign an anti-terrorism certification (ATC) and the Standard Provision on Preventing Transactions with, or the Provision of Resources or Support to, Sanctioned Groups and Individuals (Standard Provision).80 The following is long-standing language from the ATC which has proven problematic:

The phrase “all reasonable steps” is not defined, contributing to NPOs’ discomfort over the lack of clarity. A commentator to one study remarked that, generally, the meaning of this clause is vague and can encompass a broad swathe of actions.82 While this leeway can be beneficial in that it provides flexibility to NPOs in structuring their operations, it also opens NPOs to the risk of misinterpreting obligations that, if breached, could result in serious consequences.83The Recipient, to the best of its current knowledge, did not provide, within the previous ten years, and will take all reasonable steps to ensure that it does not and will not knowingly provide, material support or resources to any individual or entity that commits, attempts to commit, advocates, facilitates, or participates in terrorist acts, or has committed, attempted to commit, facilitated, or participated in terrorist acts.81

Donor conditions in CT clauses can also lead to legal action. In 2018, USAID alleged that Norwegian People's Aid (NPA) had violated the above ATC clause because its programming in Iran and Gaza led to the provision of some assistance to a designated terrorist group. NPA signed the ATC in reference to its work in South Sudan, and not Iran or Gaza, but eventually acceded to USAID's claims.84 The dispute demonstrates the breadth of the ATC and how the lack of clarity regarding scope and interpretation of its provisions can lead to problems for NPOs. The ten-year stipulation referred to above has also opened up NPOs to legal action: it was used by the Zionist Advocacy Center to argue that a USAID grant recipient had violated the ATC as the recipient had previously provided material support to groups designated as terrorist in Palestine.85

The ATC provision cited above, along with others in the ATC and the Standard Provision, was revised in 2020 after engagement between the NPO sector and USAID.86 The ATC now requires recipients to “not, within the previous three years, knowingly engage in transactions with, or provide material support or resources to, any individual or entity who was, at the time, subject to sanctions administered by the OFAC [Office of Foreign Assets Control]”.87 According to the Charity and Security Network, these revisions increase clarity by stipulating that violations must involve recipients knowingly engaging with designated groups, rather than the more unclear standard of “to the best of its current knowledge”.88 While they are positive steps, these changes are unlikely to resolve the broader concerns of NPOs discussed above.

In summary, donor conditions related to CT and sanctions pose substantial challenges for NPOs. The lack of clarity and certainty in contractual clauses, inconsistency with humanitarian principles and offloading of risk onto NPOs by donors increase the difficulties that NPOs face in delivering humanitarian assistance in sanctioned countries or areas in which designated groups operate or control territory.

Initiatives to address humanitarian challenges

Over the past five years there has been increasing recognition of the challenges that humanitarian and other non-profit organizations face related to sanctions and CT measures. The sheer volume of research, reports, webinars, surveys and anecdotal examples NPOs have raised regarding the effects on humanitarian action has begun to have an impact. Even while government officials voice scepticism and continue calls for “evidence" of direct impact of CT/sanctions policies on humanitarian action, a growing number of policy fora are acknowledging humanitarian concerns and responding.89

Stakeholder dialogues

In 2020, the UN Global Counter-Terrorism Forum (GCTF) launched the Initiative on Ensuring the Implementation of Countering the Financing of Terrorism Measures while Safeguarding Civic Space, engaging a wide range of stakeholders, including policy-makers, CFT practitioners, civil society organizations, human rights defenders and humanitarian actors. The effort focused on fostering linkages and dialogue among stakeholders to ensure that CFT policies and practices do not negatively affect civic space, human rights or humanitarian action. Co-led by the Netherlands, Morocco and the UN Office of Counter-Terrorism, and implemented by the Global Center on Cooperative Security, the GCTF convened a series of global consultations and expert-level workshops to identify lessons and develop a GCTF Good Practice Memorandum which was endorsed by GCTF members and released to the UN community in October 2021.90 Several of the work streams addressed issues of specific concern to humanitarian actors: CFT legal and policy frameworks, de-risking and financial access challenges, and multi-stakeholder dialogues. Endorsed good practices include applying CFT measures consistent with States’ obligations under international law, including IHL; enhancing reporting on the impacts of CFT measures on NPOs and humanitarian actors; protecting principled humanitarian action through safeguards in CT sanctions; and considering the potential effects of CFT measures on exclusively humanitarian activities.

National-level stakeholder dialogues are under way in several countries. In the United Kingdom, the Tri-Sector Working Group is a mechanism for dialogue between the UK government, international non-governmental organizations (INGOs) and FIs for resolving practical issues arising from INGOs working in high-risk jurisdictions and for banks who facilitate that work.91 As a result of dialogue which began in 2018, the Working Group documented evidence of the problems faced by INGOs and was successful in getting the UK government to agree to address these problems. The concept was originated through the formal recommendation of the Independent Reviewer of Terrorism Legislation, David Anderson QC, that “a dialogue be initiated to explore how to achieve the objectives of anti-terrorism law without unnecessarily prejudicing NGO's ability to deliver humanitarian aid and peace-building in parts of the world where designated and proscribed groups are active”.92

As discussed in the article by Lia van Broekhoven and Fulco van Deventer of the HSC in this issue of the Review, the Netherlands has been a leader in multi-stakeholder dialogues aimed at addressing financial access challenges. Under the leadership of the HSC as far back as 2014, meetings have been organized to discuss the experiences of Dutch NGOs and the requirements and concerns of FIs in order to explore possible solutions for Dutch stakeholders. In 2020, the Roundtable on De-Risking and Access to Financial Services for Non-Profit Organizations was formalized through an agreement of the Dutch Ministry of Finance and Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the HSC and the Dutch Association of Banks. The objective of the Roundtable is to create and maintain a confidential consultation structure in which the involved stakeholders can exchange information about the effects that NPOs experience as a result of CT financing measures to high-risk areas and sanctioned countries.

In the United States, the World Bank and the Association of Certified Anti-Money Laundering Specialists (ACAMS) organized in 2017 the Stakeholder Dialogue on De-Risking with participants from government (policy, regulatory and law enforcement authorities), international organizations, FIs and NPOs to discuss the difficulties that humanitarian organizations and charities were experiencing with financial access.93 The objectives were to foster greater understanding between NPOs, FIs and government, improve the regulatory and policy environment, and develop tools to facilitate information-sharing. Specific work streams were organized to develop standardized lists of information that banks require to conduct due diligence on NPO customers; clarify regulatory requirements and risk guidance, specifically through revision of the BSA/AML Examination Manual to implement FATF Recommendation 8;94 explore technological solutions to facilitate NPO transfers to areas of higher risk and help lower FIs’ compliance costs in providing banking services to NPOs (e.g. NPO KYC utility, e-credits, blockchain); and promote greater understanding of NPOs and broader financial access challenges though online resources and outreach. While reports and proposals were developed and the dialogue proved successful in promoting greater understanding between NPOs and banks, the effort was suspended due to a lack of engagement by US government agencies.95

In autumn of 2021, however, continued concerns by NPOs along with renewed interest in this set of issues by the Biden administration led to the establishment of the Multi-Stakeholder Financial Access Working Group by the Center for Strategic and International Studies.96 This renewed stakeholder dialogue seeks to promote greater understanding and trust among stakeholders in order to address de-risking/financial access challenges affecting humanitarian action; provide a forum for stakeholders to collaboratively explore practical options to address de-risking trends and manage risk associated with operating in high-risk jurisdictions; and develop proposals for ways in which the US government can help NPOs to manage terrorism financing, export control and sanctions risks while enabling principled humanitarian, peacebuilding and sustainable development programmes to flourish.

In 2019–20, the Swiss government sponsored a series of technical meetings known as the Compliance Dialogue on Syria-Related Humanitarian Payments,97 which resulted in the publication of the Risk Management Principles Guide for Sending Humanitarian Funds into Syria and Similar High-Risk Jurisdictions.98 The Guide provides background information and practical tips on how banks, humanitarian organizations and donors can work together to ensure that aid can reach civilians in need of assistance within Syria, in a manner which is compliant with EU/US/UN sanctions and wider regulatory obligations.

In 2020, ACAMS, the largest international membership organization dedicated to enhancing the knowledge, skills and expertise of AML/CTF, sanctions and other financial crime prevention professionals, established the International Sanctions Compliance Task Force to facilitate dialogue among sanctions specialists and subject-matter experts across a wide range of sectors.99 Of particular note, in early 2021, the Humanitarian-Sanctions Technical Dialogue Forum was formed to promote public/private discussion on risk management of permissible humanitarian transactions into highly sanctioned jurisdictions.100 The Forum includes participants from the financial sector, global corporations, international organizations, member States, humanitarian actors and sanctions regulatory authorities; it is led by Dr Justine Walker, head of global sanctions and risk at ACAMS, and co-chaired by representatives of the World Bank and European Commission.101 Following an initial focus on Yemen, Syria and Iran, the Forum is addressing how relevant actors can work within existing legal frameworks (sanctions regimes, national legislation, administrative procedures etc.) to promote viable, safe and transparent payment channels in support of international humanitarian activity involving highly sanctioned jurisdictions, with efforts in autumn 2021 specifically focused on the humanitarian situation in Afghanistan.

In addition, the French government has committed to a tripartite dialogue between bank representatives, the government (Ministry of Finance and Ministry of Foreign Affairs) and some NGOs; humanitarian actors have been calling for this dialogue since 2017. In response to NGOs’ concerns around over-compliance by banks with regulations related to CFT and sanctions, a round table was organized as part of the National Humanitarian Conference in December 2020.102 President Macron announced that practical solutions would be advanced within six months, including guidelines on “good banking practices” and procedures for requesting exemptions so that “the NGOs and the banks’ compliance departments can stabilise, structure and secure these financing channels without putting the NGOs and the banks at risk”.103 Numerous meetings organized between French NGOs and banks have reportedly addressed some aspects of the issues involved, but banks remain reluctant to address financial access-related issues. France, as president of the Council of the European Union for the first half of 2022, announced plans for a European Humanitarian Forum in early 2022, including a session focused on the impact of sanctions on humanitarian aid and the issue of bank de-risking.104

Stakeholder dialogues are also reportedly being organized or have taken place in Germany, Sweden and the Czech Republic, while discussions regarding the establishment of a potential stakeholder engagement with the EU in Brussels and the UN in New York are ongoing.

All of these discussion fora have been important in promoting greater understanding among stakeholders of mutual perspectives, and generally have resulted in better working relationships among participants, especially between NPOs and FIs. However, concrete progress in addressing the underlying problems that humanitarian actors face has been lacking. Notwithstanding the considerable efforts that have been devoted to these stakeholder dialogues, humanitarian groups and FIs remain frustrated by the absence of specific action to help remedy the financial access challenges they continue to encounter.

Increasing attention to the need to safeguard humanitarian action, and opportunities for action

Within UN bodies, there is a growing acknowledgement that humanitarian groups and other NPOs have been affected adversely by CT measures and sanctions. Numerous meetings at the UN have been organized calling for enhanced protection of humanitarian actors and action. In April 2019, Germany and France announced a “call to action” to strengthen respect for IHL and principled humanitarian action;105 this was presented to the UNSC in September 2019, with the support of forty-eight member States and the EU, with the aim of identifying concrete commitments that member States can make to better protect humanitarian space.106

On 16 July 2021, the UNSC held a ministerial meeting on the “Protection of Civilians in Armed Conflict”,107 and on 11 August 2021, an Arria-Formula Meeting on “Humanitarian Action: Overcoming Challenges in Situations of Armed Conflict and Counter-Terrorism Operations” was convened.108 The EU, together with France, Germany, Mexico, Niger, Norway and Switzerland, organized a series of discussions in New York from March to June 2021 focused on “Ensuring the Protection, Safety, and Security of Humanitarian Workers and Medical Personnel in Armed Conflicts”; the objective was to identify the main challenges for humanitarian and medical workers in armed conflicts and to explore practical solutions that can be adopted by the international community.109 Many side meetings have also been convened on the topic of CT and humanitarian action, such as the International Peace Institute's (IPI) session of 24 June 2021, entitled “Safeguarding Humanitarian Action in Counterterrorism Contexts: Addressing the Challenges of the Next Decade”, and a working round table of all stakeholders on 4–5 February 2021 focused on safeguarding humanitarian action in the 1267 regime.110

In addition to events drawing public attention to the challenges that humanitarians face, UNSC Resolution 2462 explicitly addressed the broad set of issues through language calling on member States to “ensure that measures taken to counter the financing of terrorism … comply with their obligations under international law, including international humanitarian law”.111 This language was reflected in the 7th Global Counter-Terrorism Strategy adopted in June 2021, noting that member States need to “take into account … the potential effect of [CT] measures on exclusively humanitarian activities, including medical activities, that are carried out by impartial humanitarian actors in a manner consistent with international humanitarian law”.112 The Strategy also urges States to ensure that “counter-terrorism legislation and measures do not impede humanitarian and medical activities or engagement with all relevant actors as foreseen by international humanitarian law”.113

Welcoming these changes as positive steps, the Special Rapporteur on the Promotion and Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms while Countering Terrorism noted that CT measures and sanctions “play a central role in impeding humanitarian action” and that “statements of principle are not sufficient to actively protect the integrity of humanitarian action and actors working in areas where designated groups are active”. Accordingly, she proposed recommendations to protect humanitarian action.114

Throughout 2021, some members of the UNSC consistently proposed the inclusion of humanitarian language in resolutions renewing the mandates of sanctions regimes. Drawing on language from previous resolutions, including Resolution 2462, new language was added to resolutions renewing sanctions in the CAR, DRC and Mali regimes. For example, Resolution 2582 on the DRC included new language stressing that the sanctions are “not intended to have adverse humanitarian consequences for the civilian population of the DRC” and demanding that all measures taken by States to implement sanctions “comply with their obligations under international law, including international humanitarian law, international human rights law and international refugee law, as applicable”.115 Reportedly, proposals to include a humanitarian carve-out in various sanctions regimes did not receive support.

At the end of 2021, the Security Council had opportunities to adopt new measures protecting humanitarian activities in various resolutions. Mandates of the 1267 sanctions, the 1267 and 1988 (Taliban) Monitoring Teams and the Counter-Terrorism Executive Secretariat (CTED) were addressed in December 2021, but none contained significant measures advancing the consideration of humanitarian assistance.116 The IPI, as part of its project on sanctions and humanitarian action, hosted a series of stakeholder meetings and consultations during 2021 in preparation for the UNSC's consideration of the renewal for the 1267 sanctions regime and prepared options for language protective of humanitarian action in a policy brief.117 During the negotiations for UNSC Resolution 2610 renewing the 1267 sanctions, nearly half of the members indicated support for a humanitarian carve-out, but it was not included in the final version.

As a result of the Taliban's takeover of Afghanistan on 15 August, however, the primary locus of discussions within the UNSC of humanitarian carve-outs shifted to the 1988 (Taliban) regime. The complications that long-standing UN sanctions on members of the Taliban pose for the delivery of urgently needed humanitarian assistance focused the Council's attention on the need for a humanitarian exception to the financial sanctions.

Afghanistan: Exemplar of the challenges that humanitarian actors face from sanctions/CT/de-risking measures

The most recent and consequential archetype of the challenges that humanitarian actors routinely experience related to sanctions, CT measures and financial access is epitomized in the humanitarian crisis unfolding in Afghanistan as a result of the 15 August 2021 Taliban takeover.

Even before the Taliban's return to power, Afghanistan was experiencing one of the worst humanitarian crises in the world. Decades of conflict, the COVID-19 pandemic, climatic changes and the 2021 drought had left the country in a precarious situation – it was largely dependent on foreign assistance, with 50% of its GDP provided by donors. When the Taliban took control of the Afghan government and appointed interim leaders, nearly two dozen of the country's ministries became headed by Taliban members subject to long-standing UN sanctions under the 1988 regime.118

UN sanctions prohibit member States from providing any “funds, financial assets and economic resources” to designated parties, raising questions as to whether entire ministries or even the government of Afghanistan are sanctioned. While the United States authorized general licenses for the delivery of humanitarian assistance for basic human needs in late September and December, other member States (such as the UK, Australia and the EU) indicated that they could not issue derogations to UN sanctions without an explicit humanitarian exception in a UNSC resolution.

Although many NGOs continued assistance in Afghanistan, the complications of sanctions have become overwhelming, leading the humanitarian community to call for a carve-out from the 1988 sanctions. In a statement to the UNSC Special Joint Meeting on terrorist financing threats and trends and the implementation of UNSC Resolution 2462, Ms Laetitia Courtois, ICRC permanent observer to the UN, stated: “Today we are calling for a clear carve-out in the 1988 sanctions regime for impartial humanitarian organizations engaged in exclusively humanitarian activities, and for its translation into domestic legislation. The situation in Somalia in 2010 led to a carve-out in that regime, and the need for doing so for Afghanistan now exists.”119

On 22 December 2021, after weeks of difficult negotiations, the Council unanimously adopted UNSC Resolution 2615 creating a standing exception for humanitarian assistance and other activities that support basic human needs in Afghanistan. It is not time-limited and does not include the onerous reporting requirements about which NGOs were concerned. The carve-out is essential in providing legal protection for humanitarian activities in Afghanistan, and significant in explicitly permitting “the processing and payment of funds, other financial assets or economic resources, and the provision of goods and services necessary to ensure the timely delivery of such assistance or to support such activities”.120 Even with the humanitarian exception, however, FIs demonstrate ongoing reluctance in handling payments concerning Afghanistan, in part because of the complicated interaction between UN sanctions and US domestic sanctions that target the Taliban as a group. Continuing problems that humanitarian actors (including UN agencies) face moving funds into the country make the development of safe payment channels even more vital to ensure that humanitarian assistance reaches the nearly 18 million Afghans at risk of starvation this winter.

Policy recommendations to address humanitarian challenges

The following section provides recommendations for ways to address the range of challenges that humanitarian organizations encounter in sanctioned jurisdictions and areas controlled by 1267-designated groups.

Safeguarding humanitarian action in UN sanctions and CT regimes through the adoption of legal protections

Given the impact of sanctions and CT measures on humanitarian activities and uncertainty and risk that NPOs face in sanctioned jurisdictions or areas where designated groups operate, clear legal safeguards enshrined in UNSC resolutions are necessary to protect humanitarian action and actors.

1. The UNSC should adopt resolutions excepting impartial humanitarian assistance from UN sanctions and counterterrorism measures. A range of options for safeguarding humanitarian action are possible either through amendment of the 1267 regime or by separate UNSC decisions. The boldest action would be to create a standing exception for impartial humanitarian assistance from all counterterrorism and sanctions measures.121

A. Adopt a Chapter VII resolution explicitly excepting principled humanitarian activities from the scope of all UN sanctions and counterterrorism measures. UNSC adoption of a standing humanitarian exception for impartial humanitarian actors from UN sanctions and counterterrorism measures represents the most effective way to protect humanitarian assistance. Such an exception would clarify that NPOs providing principled humanitarian assistance are free of risk of sanctions or CT violations, ensuring uniform treatment of NPOs (not just those that are implementing partners of the UN), as is the case in the Somalia sanctions regime. As the most ambitious option, this would likely be opposed by P5 States as creating risks of aid benefitting sanctioned entities and failing to differentiate risk in different geographic areas. In some States, it would likely require legislative changes and changes of national policies to implement general licenses and derogations.