Counterterrorism policies in the Middle East and North Africa: A regional perspective

Introduction

According to the 2020 Global Terrorism Index, the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region recorded the most significant decrease in terrorism-related deaths for a second year in a row, with such deaths falling by 87% since 2016 – the lowest recorded levels since 2003.1 In 2019, Algeria was among the countries to record “no deaths for the first time since at least 2011”.2 While the primary driver of these improvements can be attributed to the reduction in attacks perpetrated by the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) in MENA, Algeria's counterterrorism operations in border regions over the past decade, as well as government-run deradicalization programmes, could have contributed to the recent decline in terrorism-related deaths.3

Terrorism remains one of the most serious and widespread threats to national and international security. The 9/11 attacks and the “War on Terror” brought terrorism and counterterrorism to the forefront of politics. The securitization of policies at the national, regional and international levels in response to the threat of terrorism has been a prominent feature in the literature on terrorism in recent years. A direct consequence of the coordinated 9/11 attacks, in terms of public perception, scholarly interest and policy discourse, has been the indelible connection between terrorism and the Middle East.4 Governments in the United States and Europe have adopted counterterrorism strategies that have alternated between a coercive, “direct action” approach and more defensive and preventative measures through collaborative initiatives between States and foreign partners.5 Amid an expanding scholarly interest in terrorism and violent extremism in the post-9/11 world in general and in the MENA region in particular,6 the literature on counterterrorism policies and strategies in the region at the local and regional levels is both limited7 and predominantly Western.8 In fact, the literature tends to focus mainly on post-9/11 US–MENA or EU–MENA bilateral or multilateral collaborations as part of the global “War on Terror”. While some of the literature examines local and regional counterterrorism strategies in the region,9 only a handful offer a critical and policy-informed analysis of these models,10 and even fewer are based on empirical research and evidence.

The experience of political terrorism and violence in the Middle East throughout the 1980s and 1990s, which led to the introduction of a securitization process and the adoption of counterterrorism measures in the region, especially in the post-9/11 era, offer important lessons. Based on a review of the wider literature on counterterrorism strategies and models within the MENA region, this paper takes its point of departure from the definitional conundrum of the concepts of “terrorism” and “(national) security” within the Middle East context. It examines the evolution of the securitization process in the Middle East in response to terrorism, with reference to the experiences of countries in the region. As it analyses the different counterterrorism models and methods in the region, it argues that counterterrorism strategies in much of the Middle East have not been effective and have at times been counterproductive. The paper concludes with recommendations on how to render these strategies more effective in response to the domestic and global threat of terrorism.

Defining terrorism in the Middle East context: A legal and political conundrum

Contextualizing the costs of terrorism

The MENA region has a long history of violence and conflict. From the Mashriq to the Maghreb and for more than three decades, countries across the region have been struggling with domestic violent extremism, which has contributed either directly or indirectly to the perpetuation of conflicts in the region. The withdrawal of the Soviet Union from Afghanistan in the late 1980s, coupled with the Pakistani-induced explosion of Arab mujahideen, stimulated a wave of radical dissidence, established the basis for anti-regime violence in countries like Algeria and Libya,11 and led to a surge in the region's military spending.12 Furthermore, wars and foreign intervention, poverty and economic disparities, tribalism, sectarianism and lack of education continue to contribute to the growth and further spread of terrorism in the MENA region.13 Between 2002 and 2018, the region accounted for close to half of the world's terrorism-related casualties, while the number of terrorist attacks in the region accounted for 36.1% of the world's terrorist incidents compared to 9.8% between 1970 and 1989.14 In fact, according to the 2020 Global Terrorism Index, the largest number of deaths in the world as a result of terrorism was recorded in the MENA region between 2002 and 2019, at more than 96,000 deaths.15 Over the last two decades, the overall economic and social cost of terrorism in the region has been substantial. The overall economic cost of terrorism includes both direct material costs, caused by physical damage to property, factories, equipment and infrastructure, and indirect costs, which are far more difficult to measure. These include the value of human lives lost, the social and psychological impact of terrorism, and forgone opportunities and income resulting from terrorism-related injuries or deaths. Counterterrorism, on the other hand, includes the costs of measures and policies adopted to counter, prevent and tackle the root causes of terrorism.16

Countries or regions where terrorism or the threat of terrorism persists for a prolonged period of time suffer from other indirect, yet significant, economic losses, such as a reduction in foreign direct investments, tourism, business activity, production, and income in the services and hospitality sectors, which impact economic growth. This is particularly significant in the MENA region, where most countries depend heavily on tourism, services and foreign direct investments.17 Several factors affect the impact that terrorism has on a country's economy, including the nature and extent of each terrorist attack, the duration and persistence of such attacks, the economic resilience of the economy, and the country's existing security, economic and social structures.

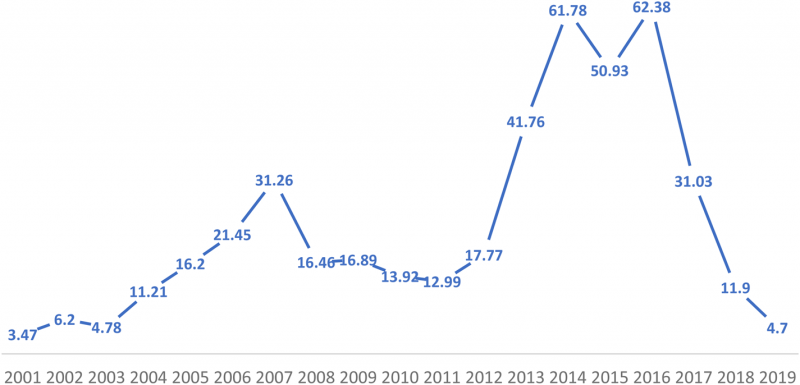

The economic cost of terrorism in the MENA region has been steadily rising since 2001, reaching a peak of over $62 billion in 2016,18 followed by a sharp decrease to $4.7 billion in 2019 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. The economic cost of terrorism in the MENA region, 2001–2019. Source: author-generated graph based on data in H. Bardwell and M. Iqbal, above note 18, and Institute for Economics and Peace, above note 1.

In 2019, 86% of the global economic impact of terrorism was recorded in three regions: Sub-Saharan Africa ($12.5 billion), South Asia ($5.6 billion) and MENA ($4.7 billion). In the MENA region, while Syria had the second-highest economic costs of terrorism as a percentage of its GDP (3.4%) in 2019, Iraq had the largest decline in economic costs from 2018 (a 71% decline, equal to $6.7 billion).19

The largest economic effect of terrorism on the economy is increased spending on defence, law enforcement and security. More recently, cyber terrorism has started to contribute more significantly to the negative economic consequences of terrorism, imposing an added layer of costs as governments and the private sector invest more in security measures to protect strategic information systems.20 In 2019, the Middle East had the world's second-highest costs in data breaches (after the United States), at $5.97 million per breach, and the world's highest average number of breached records, at 38,000 per incident.21 It is not clear, however, how many of these cyber crimes could be classed as acts of cyber terrorism.

At the same time, data on the overall costs of counterterrorism programmes and measures in the region are largely unavailable, as most MENA countries do not openly report on these costs; this makes it impossible to accurately determine the total costs of counterterrorism efforts directly tied to other expenditures, such as law enforcement or the military.22

Defining terrorism

While MENA governments have adopted domestic policies and tactics aimed at neutralizing violent groups, especially in the wake of the 9/11 attacks,23 at the heart of such policies has been the definitional conundrum of terrorism. Terrorism as a concept has been fraught with definitional challenges that go beyond the context of the MENA region. Corbin and Billet note that there is no universal and widely accepted definition of terrorism, and that most definitions are controversial due to ideological and political biases motivating the labelling of certain actions and actors based on subjective and temporal perceptions of the “enemy”.24 This definitional conundrum has been equally observed in Western countries, such as the United States, the United Kingdom and countries of the European Union (EU).

The Global Terrorism Database adopts a broad perspective and defines terrorism as “the threatened or actual use of illegal force and violence by a non-state actor to attain a political, economic, religious, or social goal through fear, coercion, or intimidation”.25 At the same time, while United Nations (UN) Security Council Resolution 1373 (2001) calls for all member States to take necessary measures to prevent and supress the financing of terrorist activities, to refrain from providing any form of assistance to persons or entities involved in terrorist activities, and to enhance cooperation among States in order to control and impede the movement of terrorists, it also leaves the task of defining “terrorism” to each country.26 In fact, as a result of the controversy and disagreement among States on a common definition of terrorism, the UN has been unable to adopt a convention against terrorism.27 Instead, the UN General Assembly tends to rely on the following definition from the 1994 Declaration on Measures to Eliminate International Terrorism:

Criminal acts intended or calculated to provoke a state of terror in the general public, a group of persons or particular persons for political purposes are in any circumstance unjustifiable, whatever the considerations of a political, philosophical, ideological, racial, ethnic, religious or any other nature that may be invoked to justify them.28

US federal law differentiates between international and domestic terrorism and defines terrorism as any crime that is dangerous to human life and appears “to be intended to intimidate or coerce a civilian population; to influence the policy of a government by intimidation or coercion; or to affect the conduct of a government by mass destruction, assassination, or kidnapping”.29 The UK Terrorism Act of 2000, on the other hand, defines terrorism as the use or threat of a specified action30 “designed to influence the government or to intimidate the public or a section of the public, and [which] is made for the purpose of advancing a political, religious or ideological cause”.31 Despite the lack of a common definition of terrorism, there are commonalities in the various approaches used to define terrorism.32 These can be summarized as:

-

having either a political, religious or generally an ideological motive;

-

committing acts aimed at causing serious psychological and/or physical damage to a group of people (who are usually not the primary target of the acts); and

-

committing these premeditated crimes with the underlying motive of influencing or pressuring governments and/or spreading a message of fear.33

Hutchison identified four core elements in defining a terrorist act: (1) the act causes emotional or physical “destructive harm”; (2) the act is committed deliberately and with the intent to cause a psychological effect; (3) the act is particularly atrocious, shocking or unpredictable; and (4) the act is often anonymous.34 “This arbitrariness of terrorist violence makes it unacceptable and abnormal.”35

Equally, across the different MENA countries, the definition of “terrorism” has been contentious and the subject of criticism in the literature.36 While the 1998 Arab Convention for the Suppression of Terrorism37 was the model upon which many terrorism laws were drawn in the region, in defining terrorism it is widely agreed that the law in most, if not all, countries relies on broad and overly vague definitions. Human Rights Watch argues that a broad definition can potentially be abused to silence political opponents, dissidents or peaceful critics of the State or the political elite, based on spurious charges.38 When it comes to definitions which are broad and overly vague, the commonly used concepts and jargon to define the legal parameters of what constitutes a terrorist act can be summed up as any act that:

- targets national unity, State security and stability;

- disturbs public order and the safety of society;

- targets territorial integrity and the normal functioning of State institutions;

- may harm the reputation of the State and obstruct the implementation of the law; and/or

- seizes or causes damage to public or private property, or damages the environment.

For example, the Algerian Penal Code defines terrorism as any act that targets “state security”, “national unity”, “territorial integrity”, and the “stability and normal functioning of institutions”.39 Determining which acts fall under these broad terminologies and concepts is largely left to the discretion of the State. The Algerian Penal Code further includes any action whose objective is to create a climate of insecurity through moral or physical assaults on people; obstruct traffic or freedom of movement on the roads; assault the symbols of the nation and the republic; unearth or desecrate graves; assault the means of transportation and transport, public and private property, or the environment; obstruct the work of public authorities, freedom of worship or the exercise of public liberties; or disrupt the functioning of public institutions.40

The overreliance on terminology such as “public order”, “national unity” and “State security” in defining a highly controversial concept like terrorism is not limited to Algeria. In fact, these are terms that have frequently been used across the MENA region.

While Saudi Arabia does not have a written and comprehensive penal code, it refers back to and applies Islamic Sharia law. In relation to crimes of terrorism, it asserts that they are part of what is referred to in Sharia as crimes of hirabah, which include “the killing and terrorization of innocent people, spreading evil on earth [al-ifsad fi al-ard], theft, looting and highway robbery”.41 At the same time, Article 1(a) of the 2013 Law Concerning Offenses of Terrorism and Its Financing refers, in defining terrorism, to acts committed with the intention to

disturb the public order, destabilize the security of society or the stability of the state, expose its national unity to danger, obstruct the implementation of the organic law or some of its provisions, harm the reputation of the state or its standing, endanger any of the state facilities or its natural resources, [or] force any of its authorities to do or abstain from doing something.42

A report by the UN Rapporteur on Counter-Terrorism and Human Rights criticized Saudi Arabia's anti-terrorism law for relying on an “objectionably broad” definition and misusing it to silence all forms of peaceful dissent, justify torture, deny freedom of expression, and imprison critics and human rights defenders.43

In a similar vein, Turkey relies on voluntarily ill-defined jargon such as “public order”, “the indivisible unity of the State” and “the attributes of the Republic” in defining terrorism. As per Article 1 of its Anti-Terror Law, terrorism is defined as:

Any criminal action conducted by one or more persons belonging to an organisation with the aim of changing the attributes of the Republic as specified in the Constitution, [or of] the political, legal, social, secular or economic system, damaging the indivisible unity of the State with its territory and nation, jeopardizing the existence of the Turkish State and the Republic, enfeebling, destroying or seizing the State authority, eliminating basic rights and freedoms, [or] damaging the internal and external security of the State, the public order or general health.44

Articles 6 and 7 of the same law refer to the publication of periodicals “involving public incitement of crimes within the framework of activities of a terrorist organisation” and the use of “propaganda for a terrorist organisation”.45 According to Amnesty International, these references have been used to silence political dissidents, academics, journalists, activists and those working in the civil society sector.46 In 2019, Amnesty International wrote that Article 7(2) of Turkey's Anti-Terror Law has been used to try 691 academics on charges of “making propaganda for a terrorist organization” just because they expressed their political opinions or views through peaceful means.47 This includes signing petitions, publishing academic articles, or giving lectures, talks or interviews.

Similarly, Morocco's Penal Code relies on the vague and broad concept of “public order” in defining terrorism and lists under Article 218bis an extensive list of acts that would “gravely undermine public order”, such as intentionally inflicting harm on the life or liberties of people; committing fraud or falsifying money; destroying, altering or damaging planes, ships or any other forms of public transport; engaging in theft or the extortion of goods; obstructing or degrading air, sea and land navigation or means of communication; the manufacture, possession, transport or circulation of illegal weapons, explosives or ammunition; engaging in offences related to automated processing systems data; participating in an association or agreement aiming to engage in acts of terrorism or intending to commit a terrorist crime; or knowingly receiving proceeds of terrorism offences.48 As in the case of Turkey, Saudi Arabia and Algeria, the reliance on a vague and broad definition of terrorist acts has also been criticized in Morocco, including by the UN Working Group for Arbitrary Detention, for enabling the “systematic criminalization of activities not related to terrorism, for example in journalism, where publishing and expressing opinions, that maybe don't correspond with those of the regime, or as free speech that denounces authorities’ abuses, can suffer scrutiny”.49

Securitization theory and countering terrorism

At the heart of the definitional conundrum of terrorism is the securitization of policies at the national, regional and international levels in response to the threat of terrorism in the post-9/11 world – a prominent feature in the literature on terrorism across Western and non-Western countries alike in recent years.

Modern terrorism can be traced back to the French anarchist movement in the mid-nineteenth century. In today's “era of securitization”,50 terrorism has become one of the most serious threats to national and international security. “Securitization” as a concept, however, pre-dates the emergence of terrorism as a policy priority, which emerged as a result of the “‘widening-deepening’ debate in security studies [that] had begun in the 1980s and intensified with the end of the Cold War”.51 Primarily developed by Barry Buzan, Ole Wæver and Jaap de Wilde, as part of what would be later known as the “Copenhagen School” of international relations theory, securitization as a concept and theory refers to the construction of an “existential threat, point of no return, and a possible way out”.52 It describes a process whereby political actors reclassify certain matters and bring them into the realm of security while employing rhetoric to ensure that the public appreciates the importance of instating exceptional measures and dedicating asymmetric resources to handle the security threat.53 Once a subject has been successfully securitized, the employment of extraordinary means (such as declaring a state of emergency or martial law, or calling in or mobilizing the military) will become widely accepted and even supported.54 It is a “move that takes politics beyond the established rules of the game and frames the issue either as a special kind of politics or as above politics”.55

There is considerable debate, however, over the distinction between the “normal” and the “exception”, with the exception generally being assumed to be “a departure from the norm of deliberative liberal-democratic politics”.56 This has raised questions in the literature over whether and how securitization theory is applicable in non-democratic contexts. In the case of the MENA region, for example, “the post-independence state has enjoyed widespread powers of control”57 and emergency laws have been prevalent for decades. Within this context, the “rules of the game” are complex and need to be understood in relative terms and within the context of the region. Pratt and Rezk argue that rather than viewing “special politics” as a break from democratic politics, “special politics” should be understood as a break from the rules that non-democratic regimes depend upon to govern.58 As such, while “normal politics” may refer to the non-democratic means employed by the State to enforce and maintain its authority, “special politics” refers to the employment of even more stringent and repressive policies.

As in other regions of the world, security strategies in the MENA region follow a “top-down” approach, where the understanding and framing of security threats from internal and external actors are determined by the State apparatus and political elite.59 Security within the Middle East context is more concerned with “regime survival, societal security, and ideological power”60 than with other, more “conventional” security concerns. In the UK context, for example, conventional security concerns mainly focus on protecting the UK, its citizens and its national and international interests, which the government claims to be grounded on a set of core values: “human rights, the rule of law, legitimate and accountable government, justice, freedom, tolerance, and opportunity for all”.61

Security in the MENA region, on the other hand, is often framed around identity, religion, sectarianism and consociationalism, nationalism and citizenship – issues that are innate to State–society relations in the region, particularly religion, which “takes on an existential importance, as a prominent feature of securitization discourse”.62 Within this context, sectarian divides have often been securitized and used as a tool to eliminate opponents, dissidents and protest groups, on the one hand, and to maintain the support of local and regional political allies, on the other.

In the wake of the Arab Uprisings, “the collapse of key long-standing regimes led to a reconstruction of the security status quo”, characterized by a radical shift in the traditional national and regional framing of security.63 While State actors remain central to how security is framed and understood both locally and regionally, inter-State dynamics and confessional/ethics discourses have changed, leading to the creation of new security actors and threats at the national level as well as new coalitions and rivalries at the regional level. Fawcett argues that on a more regional level, the Arab Uprisings contributed to “a notable resurgence in the long-standing rivalry between monarchies and republics”, a renewed Sunni–Shia confrontation and “a rising antagonism against the Muslim Brothers in the region”.64 On the local level, the region has witnessed a serious surge in tensions between “regime and society” – some of which have been promoted by external or regional actors.65 Opposition groups deemed to pose a threat to the survival of the regime have been targeted with varied strategies ranging from political reform to the use of coercive and repressive measures, often under the guise of security.66 Moreover, securitizing actors have served as a tool of solidification for the regime, as well as causing frictions and divisions between and within opposition groups, thereby changing the nature of dissent and protest movements within broader regional dynamics.67

Today, the wider literature demonstrates that both terrorism and migration have become highly securitized, receiving disproportionate resources and exceptional attention compared to other subjects on the policy agenda worldwide. The MENA region is no exception. Within the MENA context, defining, countering and preventing terrorism is confined to the realm of security, and in the aftermath of the Arab Uprisings, counterterrorism strategies have become more stringent and have frequently been targeted towards marginalizing particular opposition groups, including civil society, and eliminating opposition. This is not only contributing to a shift in the geopolitical environment across the region68 but is also changing the nature of bilateral and multilateral cooperation with the EU and the United States. Within the wider context of the changing theoretical discourse on security post-9/11, the EU and the United States have been progressively securitizing Islam, as well as their relations with Arab and Muslim countries.69 This has contributed to the prominence of counterterrorism cooperation and a rhetoric that has centralized counterterrorism in bilateral and multilateral cooperation with both the EU and the United States. Yet, such rhetoric and prominence has not translated into effective, consistent and concrete results in the field.70 If anything, it has “provided a sort of constant external legitimisation” of the securitization agenda while potentially undermining the credibility and impact of policies and programmes officially aimed at promoting democracy and human rights in the region.71 In fact, before and after the Arab Uprisings, such policies have seemed to generally prioritize short-term stability over democracy – a priority that has often failed to tackle the root causes of radicalization and violent extremism.72

A regional perspective on counterterrorism strategies

As noted at the beginning of this article, the 9/11 attacks and the “War on Terror” brought terrorism and counterterrorism to the forefront of politics, which pushed countries worldwide to adopt various counterterrorism tactics and strategies. Counterterrorism is composed of complex and varied strategies and tactics aimed at devising a holistic response to the threat of terrorism, including the adoption of anti-terror legislations, employing intelligence and countering terrorist financing tactics, as well as cooperating with other countries.73 It involves taking either a direct-action approach, such as the freezing of assets, mass arrests, destroying training camps, gathering intelligence and retaliating against a State sponsor, or taking defensive/preventative measures, such as securing borders or enforcing technological barriers.74 Although preventative measures involve actions “targeted effectively at the root cause of terrorism”, Corbin and Billet argue that most counterterrorism measures are based on a direct-action approach.75

The literature generally differentiates between “soft” and “hard” counterterrorism strategies, and these vary widely across the MENA region. Hasan et al. argue that the nature of the State significantly influences the history of violence and the policy measures and tactics adopted in response to such violence.76 In the case of Algeria, for example, where the military exercises ultimate control, counterterrorism strategies differ significantly from those adopted by a State under civilian rule, such as Turkey, or a monarchy, such as Saudi Arabia or Morocco. While all countries adopt a mix of soft and hard measures in countering or preventing terrorism, some countries adopt harder, significantly more coercive measures than others. The broad definition of terrorism widely adopted as part of the anti-terrorism legislative instruments in the MENA region facilitates the implementation of more coercive, defensive and repressive approaches, and the securitization of policies in the name of counterterrorism.

When evaluating counterterrorism policies and strategies in the region, one challenge and limitation holds true for all countries: the data are often sparse, vague or too broad.77 Statistics and qualitative data and analyses are limited, “unreliable, [and] often contradicted by the authorities themselves”.78 Moreover, a significant majority of the literature focuses on evaluating bilateral or multilateral counterterrorism cooperation between countries in the region and the EU or United States, with only a few studies adopting an in-depth analytical approach towards these policies within their local context.

The following sections evaluate the different counterterrorism measures adopted in the region in terms of their nature, legislative basis and effectiveness. They also shed light on collaborative State strategies with foreign partners, such as the United States and the EU.

Soft and hard approaches

The distinction between “soft” (non-coercive) and “hard” (coercive) approaches is important for distinguishing between coercive measures and political non-violent measures (such as rehabilitation programmes and counter-narratives) adopted by the respective governments in the region. This distinction is significant for measuring shifts that occur through time as a result of national, regional or international crises or conflicts, as well as evaluating how countries are responding to these crises. Within the MENA context, the form of government seems to play role in whether a government opts for harder or softer measures. In the case of Algeria, for example, where the military is more dominant, counterterrorism measures are generally harder than those adopted by monarchies like Saudi Arabia and Morocco, with Turkey being somewhere in the middle. Furthermore, Algeria has had a more challenging history with violent extremism and jihadism, which culminated in a civil war in 1991.

The case of Morocco is particularly noteworthy in this regard. Neefjes notes that compared to other countries in the region, Morocco stands out due to its relative “openness” and “moderate interpretation of Islam”, which creates a sense of immunity to violent extremism.79 Morocco has “a comprehensive counterterrorism strategy” that includes a mix of tactics, including “vigilant security measures, regional and international cooperation, and counter-radicalization policies”.80 The 2003 Casablanca terrorist attacks were the impetus for change in Morocco's counterterrorism policy and led to the first step towards a comprehensive strategy.81 Morocco's comprehensive counterterrorism strategy consists of three main pillars: (1) strengthening internal security, (2) fighting poverty and marginalization, and (3) controlling the religious sector and narrative in order to promote a more moderate interpretation of Islam.82

The first pillar in Morocco's counterterrorism strategy is composed of security-focused and “hard” tactics that are aimed, inter alia, at improving the performance of the country's security forces in countering terrorism, including training in cyber and crime-scene forensics, technical investigative training for the police and prosecutors, multilateral training and operational exercises to improve border security and capabilities to counter illicit traffic and terrorism, and collaborations in giving training to partners in North and West Africa.83 Morocco's “soft” counterterrorism policy focuses on the two pillars of fighting poverty and controlling the religious sector with the aim of tackling the root causes of radicalization and violent extremism. Its emphasis on education, aiding the youth in finding employment, and helping the disadvantaged and marginalized in society, as well as on adhering to the Islamic precepts of the Maliki school of thought, sets it apart from other counterterrorism policies in the region.

This differs from Algeria's approach in dealing with the religious element of terrorism, which falls under the country's hard approach to countering terrorism. As part of this approach, the Algerian government does not allow anyone other than those approved by the government to preach in mosques and prohibits the use of mosques outside of prayer hours for public meetings.84 Yet, Algeria's soft approach focuses on deradicalization and preventing young people, “a potential reservoir for guerrilla fighters”, from joining terrorist groups by putting them at the centre of the regime's economic policy and assisting them with housing and securing jobs in the public sector, among other initiatives.85 While analysts have criticized Algeria for not having a comprehensive approach to counterterrorism, it is said to be moving towards a more holistic, whole-of-government approach – one that combines hard (military) tactics for combating terrorist cells and soft (preventative) measures for tackling recruitment by jihadi Salafists and other violent groups.86 At the same time, however, given Algeria's long and gruelling experience with terrorism, the country has adopted a unique approach that recognizes its national reconciliation effort as the “backbone” of its (soft) counterterrorism strategy.87 From the outset, Algeria has adopted a community-based approach that relies heavily on the community for delegitimizing extremism and for integrating the national strategy for combating terrorism.88 Although some critics have argued that the Charter for Peace and National Reconciliation granted amnesty to recidivist terrorists, failed to provide accountability for the disappeared and victims of the civil war, and failed to examine the role of the security forces in the war, during the 2000s Algeria played a major role both economically and militarily and took the lead on a regional approach to countering terrorism in the Maghreb region.89

Saudi Arabia, on the other hand, arguably follows a holistic approach to tackling the threat of terrorism – one that addresses not only “the security aspects of the problem, but also its economic, social, cultural, educational and development dimensions, as well as its ideological and intellectual root causes”.90 Though not necessarily a comprehensive strategy, Saudi Arabia's hard approach includes programmes and actions aimed at improving the performance of security agencies by restructuring the operations of the Ministry of Interior to prevent terrorist attacks, promoting continuous training and participation in joint programmes with other countries (including European countries and the United States), exchanging intelligence information, using new technologies, and engaging community members to work with the police.91 Its soft approach includes counter-radicalization, de-radicalization and other preventative strategies, which highlights the government's conviction that terrorism cannot be defeated only by the use of force.92 Initiatives in this regard include running a prison-based programme, providing support to detainees’ families, and running an aftercare programme for released detainees, as part of the government's Prevention, Rehabilitation and Aftercare (PRAC) strategy.93

The success of the PRAC strategy led other nations to establish similar programmes modelled after Saudi Arabia's. Rehabilitation and counter-radicalization programmes that were established in Algeria, Egypt, Jordan, Yemen, Singapore, Indonesia and Malaysia in the years that followed have all been influenced, either directly or indirectly, by Saudi's leadership with such programmes.94 This success enabled Saudi Arabia to gain regional and international diplomatic leverage in the context of counterterrorism. This leverage has been demonstrated in the recent Qatar crisis, where Saudi Arabia, as part of a coalition of four Arab countries, spearheaded the imposition of an economic and diplomatic embargo on Qatar between June 2017 and January 2021. The four States accused Qatar of supporting and fuelling terrorism, supporting Shia proxies of Iran and funding extremist groups, including Hamas, the Muslim Brotherhood and the Al-Nusra Front.95 Though the Qatar crisis represented the culmination of a deteriorating relationship between Qatar and its Arab neighbours in the years following the Arab Uprisings, the embargo was mainly fuelled by these States’ interest in gaining diplomatic leverage by demonstrating their commitment to countering terrorism and combating terrorist and violent extremist groups and organizations in the region.

Anti-terrorism legislations

Anti-terrorism and counterterrorism laws across the MENA region are the legal enablers of counterterrorism policies. At the core of these legislations is the definition of terrorism adopted in the country in question. As argued in the first section of this paper, countries across the region have adopted broad and vague definitions of terrorism that are often used to intimidate and silence the opposition and “further the interests of the state, even in domains unrelated to terrorism”.96 While some States in the MENA region already had their own anti-terrorism legislation prior to the 9/11 attacks (e.g. Egypt and Algeria), MENA countries either codified or expanded their existing anti-terror laws or adopted new laws in response to the “War on Terror”.97 Significantly, since the “War on Terror”, governments in the region have frequently responded to major domestic terrorist attacks by adopting new laws or introducing amendments to their existing anti-terror legislature (see Table 1).

Table 1: Timing of domestic terrorist attacks compared to anti-terror legislation in the MENA region. Source: A. M. Wainscott, above note 5, p. 35.

This is a general pattern that is by no means unique to the MENA region. For example, the UK's 2006 Terrorism Act was adopted in the wake of the 2005 London bombings; this law introduced a number of new offences, including encouragement to terrorism, dissemination of terrorist publications, acts preparatory to terrorism, terrorist training offences, and making, misusing or possessing radioactive devices or material.98 In some countries, however, legislative amendments are not necessarily directly associated with a response to domestic terrorist attacks.99

New and amended anti-terror laws during and since the “War on Terror” have frequently been criticized for being subject to misuse and abuse. Most anti-terrorism laws in the MENA region, it is argued, have “strayed away” from their initial and primary purpose: fighting terrorism. Instead, for the most part, they are concerned with “other issues such as the maintenance of public order or indirectly the control of dissidence and political opposition, with no or scarce legal checks and balances that could restrict possible police or judiciary abuses towards civil and political rights”.100

In recent years, with the then expanding threat of the so-called Islamic State (IS), MENA countries adopted legislatures that generally strengthened existing counterterrorism provisions, broadened the definition of terrorism and terrorist offences, increased penalties for terrorism offences, expanded criminal liability to address the threat of foreign terrorist fighters, extended the jurisdiction of national courts, strengthened criminal justice institutions, and promoted regional and international legal assistance in the investigation and prosecution of terrorists, among other measures.101 For example, both Algeria and Morocco expanded their counterterrorism laws, mainly in response to the increasing threat of foreign terrorist fighters. While Morocco enacted its comprehensive counterterrorism legislation in 2003, it further broadened its definition of terrorist offences in 2015 to include joining or attempting to join terrorist organizations or groups and being involved in recruitment, activities or training for these organizations.102 It also “extended the jurisdiction of national courts to allow the prosecution of foreign nationals who commit terrorist crimes outside Morocco if they are present on Moroccan soil”.103 Similarly, Algeria added to its penal code in order to expand criminal liability in relation to foreign terrorist fighters, including for those supporting and/or financing their activities, and the use of information technology for the recruitment of terrorists, among other measures.104 These amendments are in line with UN Security Council Resolutions 2178 (2014) and 2199 (2015), and the UN Security Council ISIL and Al-Qaeda sanctions regime.105

Overall, anti-terrorism and counterterrorism laws in the MENA region are important tools for countering terrorism and deterring terrorists from committing any future terrorist crimes or offences. Yet, given the nature and frequency of terrorist attacks in the region, anti-/counterterrorism legislations in MENA countries have taken on a more restrictive and harder approach to responding to terrorism. At the core of this approach is the definitional conundrum of terrorism, where governments across the region continue to rely on vague and broad definitions that facilitate extending the remit of anti-terror laws to acts and activities unrelated to terrorism. This continues to be a major shortcoming, compounded by a failure to concentrate efforts on more preventative measures to tackle radicalization in general.

Effectiveness

The question of effectiveness is more subjective and depends on how governments and other stakeholders view and evaluate the results achieved by the different strategies adopted throughout the MENA region. Effectiveness could potentially be evaluated based on the number of potential terrorists that have been apprehended, terrorist crimes and offences that have been prevented and terrorist attacks that have been averted. In practice, however, these factors are increasingly challenging to measure and assess, both individually and collectively, in relation to a particular policy or strategy. Frequently, regimes across the region have employed mass and targeted arrests and releases as a reaction to domestic terrorist attacks, a practice which has often been criticized by human rights organizations as being retaliatory in nature. It has further been observed that there is a strong correlation between the timing of a domestic terrorist attack and mass arrests as a countermeasure, or potentially a deterrence, by regimes in the region. For example, in Morocco, in the few months after the Casablanca bombings, no less than 2,112 suspects were charged with terrorism offences.106 According to Neefjes, the fact that “an overwhelming number of suspects was apprehended … makes it almost impossible for the measures to have been strictly targeted”.107

Another potentially important measure of effectiveness is the number and nature of terrorist attacks occurring in MENA countries through time compared to the adopted legislations and policies (see Table 2, which compares terrorists attacks in different MENA countries from 1980 to 2016). Although this could indicate that a particular policy or strategy is achieving its intended results (i.e., combating terrorism), it could potentially also allude to changing national, regional or international dynamics, players and other externalities that are causing a surge or decline in domestic terrorist attacks. On the other hand, the number of attacks could also help in understanding why some MENA regimes adopt harder approaches than others – for example, why Algeria adopts a harder counterterrorism strategy compared to Morocco and Saudi Arabia.

Table 2: Total, fatal, domestic and international attacks by country in eighteen MENA countries, 1980–2016. Source: N. A. Morris, G. LaFree and E. Karlidag, above note 4, p. 160.

The case of Turkey is particularly noteworthy when it comes to the question of effectiveness. While the total number of terrorist attacks in Turkey in the period between 1980 and 2016 is among the highest in the region, the country's counterterrorism strategy has been critical in responding to and containing a multitude of terrorist threats – whether politically, ethnically or religiously motivated – both at the national and regional levels. As a result of its decades-long “intense first-hand experience”, Turkey's security structure has been particularly adaptive and its counterterrorism strategy and initiatives effectively responsive to emerging terrorist threats,108 especially by IS and other jihadist groups along the border with Iraq and Syria.

Finally, in terms of effective preventative measures, Saudi Arabia's indirect, soft counterterrorism policy, which aims at addressing factors contributing to radicalization and radical violent Islamism, provides a good example in this regard. The aforementioned Saudi PRAC strategy is composed of three interrelated programmes aimed at prevention, rehabilitation and post-release care, with the rehabilitation phase playing a major role. Launched in the aftermath of a wave of terrorist attacks in 2003, PRAC started with an impressive success rate and demonstrated a high level of effectiveness: for the first few years, the majority of those released as part of the counselling programme were not implicated in or arrested for security offences. Official statistics indicate a success rate of 80–90%, although there has been a rise in recidivism among “de-radicalised extremists” of 10–20% in recent years.109 According to Rasheed, “[o]ne of [PRAC's] salient aspects is that the programme is not punitive in nature but is rather rehabilitative for the ‘victims’ of radicalisation”.110 PRAC has been widely considered to be “the most expansive, best funded and longest continuously running counter-radicalization program in existence”, although similar programmes in the Middle East, Europe and Asia are slowly starting to emerge.111 The success of such a programme and the fact that other countries are beginning to emulate it demonstrate that a hard security response to extremism is unlikely to be effective on its own.112

Country counterterrorism cooperation

When it comes to country counterterrorism cooperation, the main international partners in the MENA region are the EU and the United States. The EU has mainly been focused on cooperating with its Southern Mediterranean partners, while the United States has directed its efforts towards the Arab Gulf – Bahrain, Iraq, Kuwait, Qatar, Oman, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates – in responding to security threats from Al-Qaeda and IS. While it is beyond the scope of this paper to examine the details of these partnerships, it is important to acknowledge some of the most prominent achievements, failures and gaps in the collaborative relationships between these actors.

The aftermath of the 9/11 attacks saw a sudden surge in international cooperation aimed at countering terrorism, where the United States has been a major player. The aim has been to build and expand on the capabilities of allies, implement stronger border protection, share intelligence, and accumulate information on terrorist fighters and cells that pose a significant danger.113 The United States has predominantly focused on kinetic efforts aimed at preventing new terrorist attacks, and hasn't dedicated the same attention and focus to building the non-kinetic capabilities of its partners, which is critical to preventing radicalization and violent extremism.114

Warrick and Paleyo argue that, given that IS is most likely working towards a comeback, it is a matter of urgency to work on expanding the United States’ civilian, non-military and non-intelligence cooperation with its MENA partners in the next few years.115 Military and intelligence cooperation between the United States and MENA countries in general, and the Arab Gulf in particular, is already well advanced. Recently, the United States and the Gulf countries have adopted a number of successful models for enhancing their counterterrorism strategies, especially in relation to terrorist financing and preventing and countering radicalization.116 A noteworthy example in this regard is the capacity-building programme under the US–Saudi Office of Program Management – Ministry of Interior.117 The programme, which is considered to be a model for other Gulf countries, “facilitates the transfer of technical knowledge, advice, skills and resources from the United States to the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia in the areas [of] critical infrastructure protection and public security, including border protection, civil defense capabilities, and coast guard and maritime capabilities”.118

The EU, on the other hand, has progressively developed its own counterterrorism strategy and architecture, particularly since the 9/11 attacks. Its initial understanding of terrorism as an essentially external threat slowly changed to capture the home-grown terrorist phenomenon as it took the first steps to develop and build its own strategy that aims to foster cooperation, adopt a proactive and cooperative approach with third countries, and enhance a common strategic vision.119 In February 2015, the European Council declared that it “needs to engage more … on counter-terrorism, particularly in the Middle East and North Africa”,120 and following a series of terrorist attacks in 2015, the EU has adopted a number of measures to combat terrorism in various key areas, including:

-

prevention of radicalisation

-

the terrorist list

-

information exchange

-

the EU counter-terrorism coordinator

-

cutting terrorist financing

-

firearms controls

-

digital justice

-

stopping foreign fighters

-

cooperation with non-EU countries.121

Furthermore, within this framework, “the EU has constantly sought to develop the international dimension of counterterrorism, with an increasing emphasis on the need to provide aid to specific targeted countries from which major concerns stem”.122 This has raised questions over the effectiveness of EU aid policy when framed within the context of securitization and counterterrorism. Within the context of the EU counterterrorism strategy, Tunisia “represents one of the most sensitive cases when facing the issue of the EU's action in cooperation with third countries in the field of counter-terrorism”.123 As the country in which “radicalisation and terrorism have spread most clearly”, Tunisia was one of the key partners in the region for the EU, especially in the aftermath of the Arab Uprisings and Tunisia's relative success in transitioning to democracy.124 In response to the threat of terrorism, Tunisia and the EU committed to intensifying their cooperation in security and counterterrorism, with a focus on migration and mobility,125 reflecting the EU's perception of terrorism as being a traditionally external threat and of migration and mobility as being serious security concerns.

Overall, these international partnerships have significantly contributed to the international response to the threat of terrorism. Yet, despite the obvious advantages of building strong and robust international partnerships for combating terrorism, it is important also to acknowledge the competing national security interests of different countries when seeking such collaborative partnerships. Countries pursue their own national interests in every other aspect of international affairs, and these international partnerships – despite an intention to respond to a common security threat – are no different. Essentially, despite some human rights, development and democratization initiatives, counterterrorism cooperation initiatives with MENA countries by both the United States and the EU have ultimately prioritized “State resilience” over “societal resilience”.126 At the core of these initiatives is the main interest of neutralizing, containing and potentially eliminating a terrorist threat “at its source” before it ever becomes a national security concern. This inadvertently turns these initiatives into the drivers for MENA regimes to develop and adopt harder and potentially more repressive counterterrorism strategies supported by draconian anti-terror laws. The fact that these international partners do not take strong positions against repression in the name of terrorism indirectly legitimizes these approaches.

Countries across the region have also been cooperating under multiple bilateral and multilateral frameworks. Examples of multilateral regional frameworks in the region include the Arab Maghreb Union, the League of Arab States, the Gulf Cooperation Council, the Organization for Islamic Cooperation, the African Union and its African Centre for Studies and Research on Terrorism, the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe, and the Middle East and North Africa Financial Action Task Force.127 The Maghreb region, in particular, has established strong collaborative partnerships when it comes to preventing and countering terrorism in the region, especially in relation to foreign terrorist fighters. For example, since 2013, Algeria has been cooperating quite extensively with Tunisia on customs, counterterrorism and border security.128 Official reports show that security cooperation between Algeria and Tunisia along the border has averted a number of terrorist attacks, with Tunisia representing an important buffer from the instability in Libya.129 Continued border security and cooperation between Algeria and Tunisia remains a top priority, “including a joint Algerian-Tunisian terrestrial and aerial force military operation against ISIS strongholds in the border area, resulting in the destruction of terrorist hideouts and homemade bombs”.130

Conclusion

Based on a review of the literature, this paper has examined the different counterterrorism strategies and models in the MENA region with the aim of highlighting the different successes and shortcomings of these policies. While the literature is both sparse and limited, especially in relation to evidence-based research on local and regional counterterrorism strategies in the region, the evidence found suggests that counterterrorism strategies in much of the region have not been effective and have at times been counterproductive.

One of the major shortcomings of counterterrorism strategies in the region is the systematic reliance on vague concepts and broad definitions in defining terrorist acts and offences. Concepts such as “national unity”, “State security”, “stability”, “public order” and the “safety of society” have enabled certain MENA regimes to extend the definition of terrorism to acts and offences that may not necessarily be related to terrorism. As a result, activists, dissidents, journalists, lawyers and those working in civil society or belonging to the political opposition have frequently been targeted and silenced through the introduction of draconian anti-terror laws. In order for counterterrorism strategies to effectively target terrorism and violent extremism, MENA regimes need to rely on clear and well-defined definitions of terrorism. Moreover, governments should refrain from enacting repressive anti-terror laws and using them as tools to further political interests and silence opposition groups. The evidence shows that while repression may be a form of deterrence in the short term, it is counterproductive in the long term, as it facilitates recruitment in violent groups and contributes to the radicalization of the youth and of marginalized people.

Secondly, the securitization of terrorism in the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks has facilitated and legitimized the use of extraordinary measures, such as declaring a state of emergency or martial law, and has shaped the nature of international partnerships, particularly with the EU and the United States. Within the MENA context, securitization follows a “top-down” approach that is mostly dictated by concerns for regime survival, State and elite interests, and controlling power dynamics and structures. As a result, efforts to prevent and counter terrorism at the national, regional and international levels employ measures that prioritize State stability and resilience over societal resilience. To effectively tackle the threat of terrorism, however, governments need to dedicate more effort and resources to preventative and deradicalization measures that focus on the potential root causes of terrorism, such as poverty, marginalization and unemployment. Despite some measures in this regard, success has been limited. Both the United States and the EU also need to enhance their efforts in developing partnerships aimed at building societal resilience, and to slowly move away from a securitized approach and towards forming partnerships in the region in order to make the most of democratization, human rights and development initiatives.

Overall, MENA regimes adopt a mix of hard and soft counterterrorism strategies. Research shows, however, that more effort is dedicated to improving the security response to terrorism, even though the evidence does not necessarily support the effectiveness of such measures. Emulating preventative, rehabilitation and aftercare programmes, as with Saudi Arabia's PRAC strategy, might prove to be more effective than adopting hard security-focused approaches. Moreover, as part of their security response, MENA regimes would benefit from improving information exchanges between the different security apparatuses and forging stronger partnerships with other countries in the region.

Lastly, in order to improve the effectiveness of counterterrorism strategies in the region, MENA regimes need to develop indicators of effectiveness in order to better understand the impact of the different policies and strategies on national efforts to prevent and counter terrorism. Adopting new anti-terror laws and introducing more amendments to existing legislature is unlikely to prevent or combat terrorism, and might even prove to be counterproductive. In fact, given the definitional conundrum of terrorism, a surge in the number of arrests (whether mass or targeted) on the back of newly introduced legislature or amendments is not necessarily an indicator of the success or effectiveness of a counterterrorism strategy. Aligning policies and strategies to measurable indicators and relying on holistic and comprehensive strategies for combating terrorism would enable MENA regimes to rely less on draconian approaches and to improve their preventative and responsive tactics with regard to terrorism.

- 1Institute for Economics and Peace, Global Terrorism Index 2020: Measuring the Impact of Terrorism, Sydney, November 2020, p. 4.

- 2Ibid., p. 1.

- 3Congressional Research Service, Algeria: In Focus, 6 July 2021, pp. 1–2, available at: https://sgp.fas.org/crs/row/IF11116.pdf (all internet references were accessed in November 2021).

- 4Nancy A. Morris, Gary LaFree and Eray Karlidag, “Counter-Terrorism Policies in the Middle East: Why Democracy Has Failed to Reduce Terrorism in the Middle East and Why Protecting Human Rights Might Be More Successful”, Criminology & Public Policy, Vol. 20, No. 1, 2020.

- 5Isaiah Corbin and Bret Billet, “An Empirical Analysis of Terrorism in the Middle East and Africa”, Wartburg College, 2014, available at: http://public.wartburg.edu/mpsurc/images/Corbin.pdf; Ann M. Wainscott, Bureaucratizing Islam: Morocco and the War on Terror, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2017.

- 6Gawdat Bahgat, “Terrorism in the Middle East”, Journal of Social, Political and Economic Studies, Vol. 32, No. 2, 2007; Bill Fletcher, “‘Terrorism’ in the Middle East”, New York Beacon, Vol. 13, No. 29, 200; Paul Thomas, Responding to the Threat of Violent Extremism: Failing to Prevent, Bloomsbury Academic, London, 2012; Sadegh Piri and Ali Yavar Piri, “The Role of the US in Terrorism in the Middle East”, Journal of Politics and Law, Vol. 9, No. 3, 201; Ihab Hanna Sawalha, “A Context-Centered Root Cause Analysis of Contemporary Terrorism”, Disaster Prevention and Management, Vol. 2, No. 2, 2017.

- 7A. M. Wainscott, above note 5.

- 8Zuzana Buronova, “An Analysis of Counter-Terrorism Strategies in Indonesia and Saudi Arabia”, master's thesis, Charles University, Faculty of Social Sciences, Czech Republic, 201.

- 9See, for example, Christopher Boucek, Saudi Arabia's “Soft” Counterterrorism Strategy: Prevention, Rehabilitation, and Aftercare, Carnegie Papers, 2008, available at: www.jstor.org/stable/resrep13021?seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents; Lotfi Sour, “The Algerian Domestic Strategy of Counter-Terrorism from Confrontation to National Reconciliation”, Romanian Review of Political Sciences and International Relations, Vol. 12, No. 2, 2015.

- 10See, for example, Eman Ragab, “Counter-Terrorism Policies in Egypt: Effectiveness and Challenges”, European Institute of the Mediterranean, 2016, available at: www.euromesco.net/publication/counter-terrorism-policies-in-egypt-effec….

- 11Francesca Galli, “The Legal and Political Implications of the Securitisation of Counter-Terrorism Measures across the Mediterranean”, European Institute of the Mediterranean, 2008, available at: www.euromesco.net/publication/the-legal-and-political-implications-of-t….

- 12Wukki Kim and Todd Sandler, “Middle East and North Africa: Terrorism and Conflicts”, Global Policy, Vol. 11, No. 4, 2020, p. 424, available at: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/1758-5899.829; Todd Sandler and Justin George, “Military Expenditure Trends for 1960–2014 and What They Reveal”, Global Policy, Vol. 7, No. 2, 2016, available at: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/1758-5899.328.

- 13Alexander R. Dawoody, Eradicating Terrorism from the Middle East: Policy and Administrative Approaches, Springer International, Cham, 2016.

- 14W. Kim and T. Sandler, above note 12, p. 424.

- 15Institute for Economics and Peace, above note 1, p. 43.

- 16Walter Enders and Eric Olson, “Measuring the Economic Costs of Terrorism”, The Oxford Handbook of the Economics of Peace and Conflict, Oxford University Press, Oxford and New York, 2012, available at: www.economics.uci.edu/~mrgarfin/OUP/papers/Enders.pdf.

- 17David Gold, Economics of Terrorism, New School University Working Paper, available at: www.files.ethz.ch/isn/10698/doc_10729_290_en.pdf.

- 18Harrison Bardwell and Mohib Iqbal, “The Economic Impact of Terrorism from 2000 to 20”, Peace Economics, Peace Science and Public Policy, Vol. 27, No. 2, 2021.

- 19Institute for Economics and Peace, above note 1, p. 32.

- 20Human Rights Council, Negative Effects of Terrorism on the Enjoyment of Human Rights: Study of the Human Rights Council Advisory Committee, UN Doc. A/HRC/AC/24/CRP.1, 22 January .

- 21Gavin Gibbon, “Middle East Data Breaches Cost $6m Each, Says New Report”, Arabian Business, 27 October 2019, available at: www.arabianbusiness.com/technology/431560-middle-east-data-breaches-cos….

- 22Anthony H. Cordesman and Abdullah Toukan, The National Security Economics of the Middle East: Comparative Spending, Burden Sharing, and Modernization, Center for Strategic and International Studies, March 2017, available at: https://tinyurl.com/mc5kstx8.

- 23F. Galli, above note 11.

- 24I. Corbin and B. Billet, above note 5; see also Z. Buronova, above note 8.

- 25I. Corbin and B. Billet, above note 5.

- 26Law Library of Congress, Algeria, Morocco, Saudi Arabia: Response to Terrorism, Global Legal Research Directorate, 2015, available at: https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/service/ll/llglrd/2016295702/2016….

- 27Council of Europe, “War and Terrorism”, 2017, available at: www.coe.int/en/web/compass/war-and-terrorism.

- 28UN General Assembly, “Declaration on Measures to Eliminate International Terrorism”, 1994, available at: https://legal.un.org/avl/ha/dot/dot.html.

- 29Legal Information Institute, “18 U.S. Code § 2331 – Definitions”, Cornell Law School, available at: www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/18/2331; see also Law Library of Congress, above note 26.

- 30A specified action is one that involves serious violence against a person or persons or endangers the life of others, causes serious damage to property, causes serious risk to the health or safety of the public or a section of the public, or interferes with or seriously disrupts basic infrastructures. See Council of Europe, Profiles on Counter-Terrorist Capacity: United Kingdom, Committee of Experts on Terrorism (CODEXTER), 2007, available at: www.legislationline.org/download/id/3145/file/UK_CODEXTER_Profile_2007….

- 31Ibid.

- 32Z. Buronova, above note 8.

- 33International Social Science Council, Hazards Information Profile on Violence, Paris (in press); Z. Buronova, above note 8.

- 34Marta Crenshaw Hutchinson, “The Concept of Revolutionary Terrorism”, Journal of Conflict Resolution, Vol. 16, No. 3, 1972, available at: www.jstor.org/stable/173583; see also Kelsey Lilley, “A Policy of Violence: The Case of Algeria”, Davidson College, E-International Relations, 2012, available at: www.e-ir.info/2012/09/12/a-policy-of-violence-the-case-of-algeria/.

- 35M. Crenshaw Hutchinson, above note 34.

- 36See, for example, Human Rights Watch, “Saudi Arabia: New Counterterrorism Law Enables Abuse”, 23 November 2017, available at: https://www.hrw.org/news/2017/11/23/saudi-arabia-new-counterterrorism-l…; Francesco Tamburini, “Anti-Terrorism Laws in the Maghreb Countries: The Mirror of a Democratic Transition that Never Was”, Journal of Asian and African Studies, Vol. 53, No. 8, 2018; Amnesty International, “Turkey: Measures to Prevent Terrorism Financing Abusively Target Civil Society and Set Dangerous International Precedent”, 17 June 2021, available at: www.amnesty.org/en/latest/press-release/2021/06/turkey-measures-to-prev….

- 37The Arab Convention for the Suppression of Terrorism defines terrorism as “[a]ny act or threat of violence, whatever its motives or purposes, that occurs in the advancement of an individual or collective criminal agenda and seeking to sow panic among people, causing fear by harming them, or placing their lives, liberty or security in danger, or seeking to cause damage to the environment or to public or private installations or property or to [occupy] or seiz[e] them, or seeking to jeopardise a national resource”. Arab Convention on the Suppression of Terrorism, 22 April 1998, Art. 1(2), available at: www.refworld.org/docid/3de5e4984.html. The Convention was adopted within the framework of the League of Arab States and was signed by the ministers of justice and interior of all the Arab member States. As of 2004, seventeen countries have deposited instruments of ratification with the General Secretariat of the League of Arab States. A full list of these countries is available at: www.un.org/unispal/document/auto-insert-186442/.

- 38Human Rights Watch, above note 36.

- 39Law Library of Congress, above note 26.

- 40Ibid.

- 41Ibid.

- 42Ibid.

- 43Human Rights Council, Report of the Special Rapporteur on the Promotion and Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms while Countering Terrorism on his Mission to Saudi Arabia, UN Doc. A/HRC/40/XX/Add.2, 6 June 2018, pp. 5–6, available at: www.ohchr.org/Documents/Issues/Terrorism/SR/A.HRC.40.%20XX.Add.2SaudiAr…; see also Patrick Wintour, “UN Accuses Saudi Arabia of Using Anti-Terror Laws to Justify Torture”, The Guardian, 6 June 2018, available at: www.theguardian.com/world/2018/jun/06/un-accuses-saudi-arabia-of-using-….

- 44Turkey, Law to Fight Terrorism, Act No. 3713, 12 April 1991 (amended 1995, 1999, 2003, 2006, 2010) (Anti-Terror Law), available at: www.legislationline.org/download/id/3727/file/Turkey_anti_terr_1991_am2….

- 45Ibid.

- 46See, for example, Amnesty International, Turkey: Deepening Backslide in Human Rights, Submission for the UN Universal Periodic Review, 35th Session of the UPR Working Group, 7 August 2019, available at: www.amnesty.org/en/documents/eur44/0834/2019/en/.

- 47Amnesty International, “Turkey: First Academic to Go to Prison for Signing Peace Petition in a Flagrant Breach of Freedom of Expression”, 29 April 2019, available at: www.amnesty.org/en/documents/eur44/0290/2019/en/.

- 48Morocco, Code Pénal, 26 November 1962, available at: www.refworld.org/docid/54294d164.html; Albert Caramés Boada (ed.) and Júlia Fernàndez Molina, No Security without Rights: Human Rights Violations in the Euro-Mediterranean Region as Consequence of the Anti-Terrorist Legislations, International Institute for Nonviolent Action, 2017.

- 49A. Caramés Boada (ed.) and J. Fernàndez Molina, above note 48. See also Human Rights Council, Report of the Working Group on Arbitrary Detention: Mission to Morocco, UN Doc. A/HRC/27/48/Add.5, 4 August 2014, available at: www.ohchr.org/EN/HRBodies/HRC/RegularSessions/Session31/Documents/A-HRC….

- 50Uzzi Ohana, “The Securitisation of Others: Fear, Terror, Identity”, Sixth Pan-European Conference of International Relations: Making Sense of a Pluralist World, University of Turin, 12–15 September 2007.

- 51Christian Kaunert and Sarah Leonard, “The Collective Securitisation of Terrorism in the European Union”, UWE Bristol Research Repository, 2018, p. 3, available at: https://uwe-repository.worktribe.com/OutputFile/856849.

- 52Barry Buzan, Ole Wæver and Jaap de Wilde, Security: A New Framework for Analysis, Lynne Rienner, Boulder, CO, 1998, p. 21.

- 53Saud Al-Sharafat, “Securitization of the Coronavirus Crisis in Jordan: Successes and Limitations”, Washington Institute, Fikra Forum, 11 May 2020, available at: www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/securitization-coronavirus-….

- 54Ibid.

- 55F. Galli, above note 11, p. 5; see also Simon Mabon, “Existential Threats and Regulating Life: Securitization in the Contemporary Middle East”, Global Discourse, Vol. 8, No. 1, 2018, available at: https://eprints.lancs.ac.uk/id/eprint/89177/1/Existential_Threats_and_R….

- 56Nicola Pratt and Dina Rezk, “Securitizing the Muslim Brotherhood: State Violence and Authoritarianism in Egypt after the Arab Spring”, Security Dialogue, Vol. 50, No. 3, 2019, p. 241; see also Juha A. Vuori, “Illocutionary Logic and Strands of Securitization: Applying the Theory of Securitization to the Study of Non-Democratic Political Orders”, European Journal of International Relations, Vol. 14, No. 1, 2008.

- 57N. Pratt and D. Rezk, above note 56, p. 241.

- 58Ibid.

- 59S. Mabon, above note 55, p. 3.

- 60Ibid.

- 61UK Cabinet Office, The National Security Strategy of the United Kingdom: Security in an Interdependent World, March 2008, available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uplo….

- 62S. Mabon, above note 55, p. 3.

- 63Louise Fawcett, International Relations of the Middle East, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2019, p. 219.

- 64Ibid.

- 65S. Mabon, above note 55, p. 5.

- 66Ibid.

- 67Ibid.

- 68Ibid.

- 69F. Galli, above note 11.

- 70Stefano M. Torelli, “European Union and the External Dimension of Security: Supporting Tunisia as a Model in Counter-Terrorism Cooperation”, European Institute of the Mediterranean, 2017, available at: www.euromesco.net/publication/the-european-union-and-the-external-dimen….

- 71Ibid., p. 21.

- 72Ibid.

- 73Z. Buronova, above note 8.

- 74I. Corbin and B. Billet, above note 5.

- 75Ibid., p. 3.

- 76Noorhaidi Hasan, Bertus Hendriks, Floor Janssen and Roel Meijer, Counter-Terrorism Strategies in Indonesia, Algeria and Saudi Arabia, ed. Roel Meijer, Netherlands Institute of International Relations Clingendael, 2012, available at: www.ojp.gov/ncjrs/virtual-library/abstracts/counter-terrorism-strategie….

- 77Ibid.

- 78Ibid., p. 6.

- 79Ricardo Neefjes, “Counterterrorism Policy in Morocco”, master's thesis, Utrecht University, Faculty of Humanities, 2017, available at: http://dspace.library.uu.nl/handle/1874/353663; Benjamin Aziza, “Morocco's Unique Approach to Countering Violent Extremism and Terrorism”, Small Wars Journal, 21 December 2018, available at: https://smallwarsjournal.com/jrnl/art/moroccos-unique-approach-counteri….

- 80Law Library of Congress, above note 26, p. 12; see also Mohamed El Dahshan and Mohammed Masbah, Synergy in North Africa: Furthering Cooperation, Chatham House, January 2020, available at: www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/2020-01-2020-Synergy-North-Afr….

- 81R. Neefjes, above note 79. See also Mohammed Masbah, “The Limits of Morocco's Attempt to Comprehensively Counter Violent Extremism”, Middle East Brief, No. 118, Brandeis University, May 2018, available at: www.brandeis.edu/crown/publications/middle-east-briefs/pdfs/101-200/meb….

- 82R. Neefjes, above note 79; Clive Williams, “Counterterrorism Cooperation in the Maghreb: Morocco Looks Beyond Marrakech”, The Strategist, Australian Strategic Policy Institute, 12 December 2018, available at: www.aspistrategist.org.au/counterterrorism-cooperation-in-the-maghreb-m….

- 83Law Library of Congress, above note 26; Assia Bensalah Alaoui, “Morocco's Security Strategy: Preventing Terrorism and Countering Terrorism”, European View, Vol. 16, 2017, available at: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12290-017-0449-3.

- 84Law Library of Congress, above note 26.

- 85Lotfi Sour, “The Algerian Domestic Strategy of Counter-Terrorism from Confrontation to National Reconciliation”, Romanian Review of Political Sciences and International Relations, Vol. 12, No. 2, 2015; Michael Greco, “Algeria's Strategy to Overcome Regional Terrorism”, The National Interest, 27 February 2019, available at: https://nationalinterest.org/feature/algerias-strategy-overcome-regiona….

- 86Law Library of Congress, above note 26; Anna Louise Strachan, The Security Sector and Stability in Algeria, K4D Helpdesk Report, UKAid, 29 May 2018, available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5b4874e5ed915d48048316ae…. See also US Department of State, “Country Reports on Terrorism 2019: Algeria”, Bureau of Counterterrorism, 2019, available at: www.state.gov/reports/country-reports-on-terrorism-2019/algeria/.

- 87L. Sour, above note 85; see also Ellie B. Hearne and Nur Laiq, “A New Approach? Deradicalization Programs and Counterterrorism”, International Peace Institute, June 2010, pp. 3–4, available at: www.ipinst.org/wp-content/uploads/publications/a_new_approach_epub.pdf.

- 88L. Sour, above note 85.

- 89Alexis Arieff, Algeria: Current Issues, Congressional Research Service, 22 February 2011, available at: https://tinyurl.com/tmvbwjc6; US Department of State, Integrated Country Strategy: Algeria, 18 September 2018, p. 2, available at: www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/ICS-Algeria_UNCLASS-508.pdf. See also Rasheed Oyewole Olaniyi, “Algeria: The Struggle against Al-Qaeda in the Maghreb”, in Usman A. Tar (ed.), Routledge Handbook of Counterterrorism and Counterinsurgency in Africa, Routledge, Abingdon, 2021.

- 90Human Rights Council, above note 20, p. 1.

- 91Law Library of Congress, above note 26.

- 92Z. Buronova, above note 8.

- 93Ibid.

- 94Ibid., p. 1.

- 95Patrick Wintour, “Gulf Plunged into Diplomatic Crisis as Countries Cut Ties with Qatar”, The Guardian, 5 June 2017, available at: www.theguardian.com/world/2017/jun/05/saudi-arabia-and-bahrain-break-di….

- 96A. M. Wainscott, above note 5, p. 32.

- 97Ibid.

- 98Council of Europe, Profiles on Counter-Terrorist Capacity: United Kingdom, CODEXTER, April 2017, available at: www.legislationline.org/download/id/3145/file/UK_CODEXTER_Profile_2007….

- 99A. M. Wainscott, above note 5.

- 100F. Tamburini, above note 36, p. 1.

- 101US Department of State, Country Reports on Terrorism 2016, Bureau of Counterterrorism, July 2017, available at: www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/crt_2016.pdf.

- 102Morocco, Law to Combat Terror, Law No. 03-03, Official Bulletin of the Kingdom of Morocco, No. 5112, 29 May 2003; Morocco, Bill to Amend Counterterrorism Law, Law No. 86.14, Official Bulletin of the Kingdom of Morocco, No. 6365, June 2015.

- 103US Department of State, above note 101, p. 210.

- 104A. Arieff, above note 89.

- 105Ibid.

- 106R. Neefjes, above note 79, p. 21.

- 107Ibid.

- 108John T. Nugent, “The Defeat of Turkish Hizballah as a Model for Counter-Terrorism Strategy”, Calhoun: The NPS Institutional Archive, 2004, available at: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/36729892.pdf.

- 109Adil Rasheed, “Countering the Threat of Radicalisation: Theories, Programmes and Challenges”, Journal of Defence Studies, Vol. 10, No. 2, 2016, pp. 57–58, available at: https://idsa.in/system/files/jds/jds_10_2_2016_countering-the-threat-of…; Sara Brzuszkiewicz, “Saudi Arabia: The De-Radicalization Program Seen from Within”, Italian Institute for International Political Studies, 28 April 2017, available at: www.ispionline.it/en/pubblicazione/saudi-arabia-de-radicalization-progr….

- 110A. Rasheed, above note 109, p. 58.

- 111C. Boucek, above note 9, pp. 22–23.

- 112Ibid.

- 113Matthew Levitt et al., “The Future of Regional Cooperation in the War on Terror”, Washington Institute for Near East Policy, PolicyWatch 3019, 19 September 2018, available at: www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/future-regional-cooperation….

- 114Ibid.

- 115Thomas Warrick and Joze Paleyo, Improving Counterterrorism and Law Enforcement Cooperation between the United States and the Arab Gulf States, Atlantic Council. Scowcroft Middle East Security Initiative, 2020, p. 1, available at: www.atlanticcouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/CTLE-Task-Force-Repo….

- 116Ibid.

- 117Ibid.

- 118Ibid., p. 26.

- 119S. M. Torelli, above note 70, p. 13.

- 120European Parliament, “Question for Written Answer E-003442-15”, 3 March 2015, available at: www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/E-8-2015-003442_EN.html.

- 121European Council, “The EU's Response to Terrorism”, General Secretariat of the Council, available at: www.consilium.europa.eu/en/policies/fight-against-terrorism/.

- 122S. M. Torelli, above note 70, p. 11.

- 123Ibid., p. 27.

- 124Ibid.

- 125European Commission, Joint Proposal for a Council Decision, JOIN(2018) 9 Final 2018/0120(NLE), Brussels, 2019, available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:52018JC0….

- 126See, for example, C. Kaunert and S. Leonard, above note 51.