Building the case for a social and behaviour change approach to prevent and respond to the recruitment and use of children by armed forces and armed groups

Over the last decade, social and behaviour change strategies have increasingly been used to address human rights and child protection concerns, including harmful practices such as child marriage, female genital mutilation and violent discipline. Social and gender norms have also been recognized as key drivers of child recruitment. Nonetheless, the use of social and behaviour change strategies to prevent and respond to the recruitment and use of children in armed conflict has not yet been systematically explored or applied. Building on academic and practical sources, including findings from studies by the International Committee of the Red Cross and United Nations University, social and behavioural science theory, experiences from the Monitoring and Reporting Mechanism on grave violations against children, and academic literature, this article explores how social and behaviour change approaches can inform prevention of and response to the recruitment and use of children in armed conflict. The article concludes that social and behaviour change approaches can effectively inform prevention and reintegration efforts and can facilitate responses that bridge the humanitarian, development and peace nexus. Using social and behaviour change approaches can help to reveal why children are recruited from the perspective of key actors and entities across the socio-ecological framework in order to prevent the practice from becoming more accepted.

* Line Baago̷-Rasmussen is Social and Behaviour Change Specialist in Education and Safe to Learn Global Coordinator, UNICEF; Carin Atterby is Child Protection Adviser, Plan International Sweden, Stockholm, Sweden; Laurent Dutordoir is Humanitarian Policy Manager, Office of Emergency Operations, UNICEF. Corresponding author: Line Baagø-Rasmussen; email: linebaago@gmail.com

This article is written in the authors’ personal capacities and does not necessarily represent the views of any institution with which they are affiliated.

Introduction

Over the last decade, social and behaviour change strategies have increasingly been used to address child protection concerns, including harmful practices such as child marriage, female genital mutilation and violent discipline.1 Social and gender norms have also been recognized as key drivers of child recruitment.2 Nonetheless, the use of social and behaviour change strategies to prevent and respond to the recruitment and use of boys and girls3 in armed conflict has not yet been systematically explored or applied.

This article explores how social and behaviour change approaches can strengthen prevention of and response to the recruitment and use of boys and girls in armed conflict. It builds on an increasing body of literature and guidance seeking to leverage social and behavioural science and social and behaviour change strategies to promote positive outcomes for children with respect to violence prevention.

In 2021, the United Nations (UN) Secretary-General released a guidance note on behavioural science urging UN entities to “explore and apply behavioural science in programmatic and administrative areas”4 in order to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals, including on violence prevention. Yet, in current practice there is a need for an enhanced focus on how to change the behaviours of boys and girls, their caregivers, communities, and parties to conflict, as a preventive method and response strategy to child recruitment. Furthermore, inadequate attention has been paid to how social and gender norms are both replicated and challenged in the conduct of armed groups. This has resulted in a lack of attention to the differentiated needs of boys and girls in the release and reintegration processes.

Limitations and purpose

To demonstrate how social and behaviour change approaches can be applied to understand why children are being recruited, we use available research on the drivers of child recruitment. Sometimes we present assumptions to illustrate what a social and behavioural approach might look like in prevention and response efforts to child recruitment. In practice, formative research from the specific locality of intervention is needed to identify the drivers in each context and help answer the question of why the practice is happening.5 It is our hope that this article will contribute by providing an approach and methodology for identifying the social and behavioural drivers of the practice, and insights on how to better address it through evidence-based interventions targeting these drivers.

The normative framework on recruitment and use of children in armed conflict

More than twenty-five years have passed since the publication of the report Impact of Armed Conflict on Children by Graça Machel.6 The report, commissioned by the UN General Assembly, concluded that armed conflict disproportionately impacts children and identified children as the primary victims of armed conflict. The report marked the beginning of the UN-wide effort to improve the situation of children in armed conflict.

Included as one of the six grave violations against children in armed conflict, recruitment and use of children is defined as the “compulsory, forced and voluntary conscription or enlistment of children into any kind of armed force or armed group”.7 The Paris Principles define a child associated with an armed force or armed group as

[a]ny person below 18 years of age who is or who has been recruited or used by an armed force or armed group in any capacity, including but not limited to children, boys and girls, used as fighters, cooks, porters, messengers, spies or for sexual purposes. It does not only refer to a child who is taking or has taken a direct part in hostilities.8

The recruitment and use of children under the age of 15 is prohibited in international humanitarian law (IHL) and international human rights law.9 This has been further strengthened by the Optional Protocol on the Involvement of Children in Armed Conflict to the Convention on the Rights of the Child, which requires States Parties to increase the minimum age for compulsory recruitment and for direct participation in hostilities to 18 years.10 The Optional Protocol also prohibits non-State armed groups from recruiting or using children under the age of 18. In addition to these international frameworks, there are regional and national frameworks that prohibit or limit the recruitment and use of children – for example, the African Union's African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child, which prohibits the recruitment and use of any child.11

Though legal protections for children affected by armed conflict have been strengthened over recent decades, children's rights are continuously violated by parties to conflict across the world. In fact, the last decade has seen an increase in the recruitment and use of children in certain locations, including, for instance, across countries in the Middle East. In the 2022 report of the UN Secretary-General on Children and Armed Conflict, the UN verified the continued recruitment and use of children in twenty-three out of the twenty-four situations covered in the report.12 In total more than 7,600 children were verified as having been recruited and used, in cases attributed to more than fifty-five parties listed in the report.13 Due to the continued prevalence of high-intensity conflicts and protracted crises, it is most likely that child recruitment will remain a standing protection concern for children affected by armed conflict.

Conceptual framework for applying social and behaviour change strategies

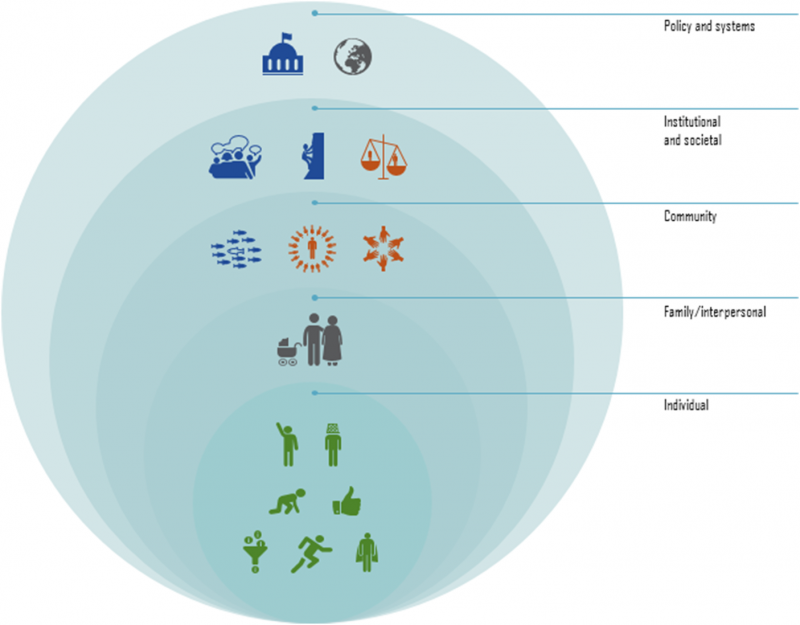

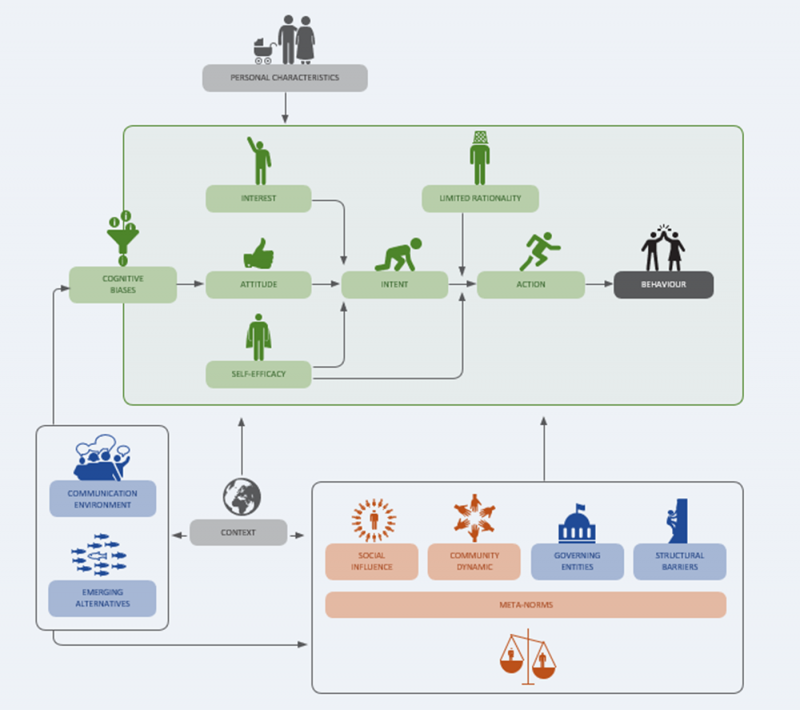

There are multiple drivers that influence human behaviours at different levels, and a number of conceptual models have been developed to map these.14 In this article we explore how conceptual frameworks can guide social and behaviour change programming to prevent child recruitment using the socio-ecological model15 and the behavioural drivers model.16 These models are illustrated in Figure 1 and Figure 2 below.

Of the various behavioural factors that may influence a practice, social and gender norms are central to behaviour change strategies. Notably, not all behavioural factors will be relevant to tackling a practice. Social and gender norms may not always play a role, but when they do, it is necessary to understand and leverage them to ensure effective interventions. We will start by briefly outlining the theoretical concepts of social and gender norms, and we will then use this understanding to explain how these can be leveraged in social and behaviour change programming to prevent the recruitment and use of children in armed conflicts.

What are social and gender norms?

Social norms are informal rules of behaviour in a group that guide what is considered socially acceptable for members of the group.17 Social norms are expectations that guide how we think other people want us to behave in our families, communities and society, regardless of whether such perceptions are true.18

Gender norms are defined by expected attitudes and behaviours relating to gender. They are part of socialization and are learned from childhood. They can be defined as the social rules and expectations that keep gendered roles in place. Gender norms define the roles, duties and responsibilities expected of women, girls, men and boys.19 They reflect and perpetuate inequitable power relations across the socio-ecological framework, from the policy and institutional levels to the individual level, and are most often disadvantageous for women.20

Social and gender norms that promote or enable violence, such as communities practicing child marriage or subjecting children to violent discipline, usually evolve over time. Groups and individuals conform to certain behaviours that become perceived as normal. In the process of this evolution, social and gender norms across the personality of individuals and institutions can change in ways that allow for violence to become more accepted and normalized and therefore more likely to occur21 – or the other way around. The recruitment and use of children in armed conflict can also be the result of changing norms in the context of conflict that contribute to the practice becoming more widespread and accepted.

What is social norms theory?

Social norms theory can help explain why groups differ from each other – for example, why one police force may use more aggressive interrogation tactics than another, or why people in some places practice child marriage and others do not.22 The influence of social norms is linked to membership of a group. To change a specific behaviour, it is necessary to identify whether it is governed by social norms and/or by other behavioural factors. The following five key concepts23 can help us to identify social norms.24

-

Reference network: The group of people around us, whose opinion matters to us. The individuals in a reference network influence how we make our decisions, because we want to be accepted and to belong to the same group as them.

-

Normative expectations: What we believe our reference network considers right, or what we believe it expects us to do. Our human desire for acceptance will cause us to conform to the believed expectations.

-

Empirical expectations: Beliefs we hold about what others in the group do. We may mistakenly think behaviours are more typical than they really are. This can lead to behaviours being widespread in a group, even if sometimes most people privately disapprove of them and would prefer to do otherwise. These misconceptions are called pluralistic ignorance.

-

Sanctions: Social norms are maintained based on approval and disapproval of the reference group. When we follow the rules, we are socially rewarded, e.g. accepted, praised or honoured. If we break them, we are socially punished or sanctioned. This social pressure to comply can take many forms, including public mockery, stigma, exclusion and violence.

In focus 1: Parents’ acceptance of or opposition to child recruitment

Caregivers may agree to let their children join armed forces or armed groups because it is practiced by other members of the community who matter to them (reference network). In addition to other enabling factors to child recruitment, such as lack of education and livelihood opportunities, parents may believe that the other members of the community expect them to let their children join armed forces or armed groups (normative expectation), and they may worry that they will be criticized or ill-treated (sanctions) if they do not conform to the norm of agreeing to let their children join armed forces or armed groups, or encouraging them to do so. The situation could, however, be entirely different: it is possible that most of the community members privately think that child recruitment is wrong and would prefer not to allow it. At the same time, most community members may think that everyone around them endorses child recruitment, so they adapt to the practice (pluralistic ignorance).

Social norms in a group do not always reflect the private opinion or values of individual members, and as a result may diverge from what the group considers desirable and appropriate behaviour. Conceptualizing social behaviour as a representation of the group clarifies how and when these divergences occur. This can help to explain why customary practices such as child marriage and female genital mutilation continue, even after individuals have been convinced of their damaging effects or have changed their attitude towards these practices.25 This has also been described as the differentiation between individuals’ attitude towards a norm versus the perception of a norm. Attitude change refers to changing how a person personally feels about a behaviour, while norm change refers to changing an individuals’ perception of others’ feelings or behaviours26 (normative expectations). With respect to how norm perception can be changed, three non-exhaustive ways are explained here: (1) individual behaviour, (2) group summary information, and (3) institutional signals. People can be influenced by individual public behaviour in their reference group, such as gossip, observation or humour; by summary information about a group's opinions and behaviour through announcements, statistics or news (this can be particularly useful for addressing pluralistic ignorance); or by institutional systems, such as public rules, punishments and rewards.27

The socio-ecological model, shown in Figure 1, displays the interplay between the individual, parents/caregivers, family, community, institutional/societal and policy/system levels. The socio-ecological model is used to understand the different levels at which norms, behaviours and practices may influence the lives of children, and to identify what can protect them at each level.28 By combining programming at different levels, our interventions can be more effective in generating change. Social and behaviour change research also allows for identifying positive behaviours that can promote peace and social cohesion or mitigate local conflict, for instance through traditional mechanisms or key influencers that can be promoted positively as part of interventions.

What are social and behavioural drivers?

To develop an evidence-based social and behaviour change strategy to address the recruitment and use of children, it is necessary to identify the drivers of the practice. If we can identify the drivers of child recruitment, we can also determine which of these drivers to target and then build our prevention and response strategy around that information. As mentioned above, not all factors will be relevant for a given practice, and social and gender norms will not necessarily always be at play. As such, social and gender norms form part of the different drivers that can influence social change and behaviours.

The drivers influencing our behaviour can be broadly put into three categories: (1) psychology – our personal thoughts/brain; (2) sociology – influence by the surrounding society; and (3) environment – the context and institutions that surround us.29 Figure 2 displays the behavioural drivers model, which shows different factors that may influence a given behaviour across these three categories. Each category depicts different drivers that may influence a particular behaviour, such as community dynamics, attitudes, and governing entities.30 Formative research can help to identify which drivers influence child recruitment, and our interventions should target these drivers to be effective. In other words, the behavioural drivers model shows potential drivers that may influence the practice of child recruitment and helps conceptualize how social and behaviour change programming can address this practice.

The key is to understand why child recruitment is happening or considered acceptable. Quantitative data such as data from the UN Monitoring and Reporting Mechanism (MRM)31 in some country situations, national household surveys such as the Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys, and existing research on the impact of armed conflict on children can be used to develop a contextual analysis mapping the prevalence and geographic scope of child recruitment. However, to understand why the practice is happening, qualitative research is also required. While it is beyond the scope of this article to outline practical tools, there are numerous resources on how to conduct quality social and behaviour change research.32 Using research findings, we can establish and prioritize which behavioural drivers are influencing the practice that we want to change. For example, the formative research may identify social influence, self-efficacy and governing entities as having a key influence on the practice of child recruitment, meaning that we would need to build our programming with a focus on those drivers. The examples in the below section on “Putting It All Together” explain how the behavioural drivers model can be used to identify and analyze the drivers and couple them with interventions, mindful that all relevant factors driving a given behaviour would need to be addressed for the interventions to be effective.

Unpacking the idea: How to apply a social and behavioural approach to the issue of child recruitment?

To conceptualize potential drivers of child recruitment, it is necessary to identify the key groups of people who may have an influence on the practice of child recruitment (reference network). This can be done by conducting a mapping exercise of reference networks in the given context, and the roles that individuals (e.g., parents, teachers, community leaders, commanders) play in those networks. The mapping exercise should also map the types of relationships within and between the networks linked to the socio-ecological model.33 In this paper, we are working with certain assumptions and available research around the drivers of child recruitment to illustrate what the use of a social and behavioural approach might look like in prevention and response efforts to child recruitment. As mentioned in the introduction, in practice formative research from the specific locality of intervention is needed to identify the drivers in each context.34

For the purposes of this paper, we will consider the following groups and corresponding networks in relation to child recruitment:35

-

The recruiters (armed forces or armed groups).

-

The recruited (children).

-

The protective environment:

-

The community.

-

The parents/caregivers and families.

-

Peers/interpersonal.

-

These groups are interconnected, with various relationships between each other, and need to be explored at multiple levels. If we can understand the social and behavioural drivers that influence these actors, we may be able to understand why children are recruited. Such information can inform the design of more effective and sustainable prevention and response interventions.

The community, parents, and peers are particularly important for children's “protective environment”. These actors comprise the inner circles in the socio-ecological model: they are supposed to protect children from harm, although they may also cause harm.

The recruiters: Members of armed forces and armed groups

When applying a social and behavioural change lens to understand why armed forces and armed groups recruit boys and girls,36 we must understand what governs the behaviour of these groups. Group membership builds on norms, socialization and behaviours that determine what is acceptable and what is not acceptable in a specific group. For example, police officers may use the behaviour of their peers as a guide to what constitutes an appropriate level of force.37 In the same way, members of armed forces and armed groups may use the behaviour of other group members as an element in guiding whether recruitment and use of children in armed conflict is acceptable or not.

Studies by the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) highlight the importance of analyzing the structure and level of centralization of armed groups, combined with identifying the sources of influence on how members of such groups behave, in order to develop meaningful engagements and interventions with those groups.

The ICRC's 2004 study on The Roots of Behaviour in War38 focuses on the integration of IHL across all levels of armed forces and structured armed groups, and places emphasis on punishment as a key motivation for restraint. The 2018 follow-up study on The Roots of Restraint in War39 goes deeper in exploring the decisive role of organizational structure, socialization, and value-based motivation in establishing restraint among soldiers and fighters across four different levels of organization. These four levels are integrated State armed forces, centralized non-State armed groups, decentralized non-State armed groups and community-embedded armed groups. Findings across the four categories of groups highlight that internalization of values through socialization is a more effective way of preventing IHL violations and promoting restraint than the threat of lawful sanction only; a combination of both is most effective. This indicates that understanding the social and behavioural drivers which govern armed groups can be key to promoting restraint, including preventing recruitment and use of children by armed forces and armed groups.

Building on findings from the two ICRC studies and drawing on the social and behaviour change theory and models presented above, the following sections explore hierarchical influences, peer group influences and external influences across the four levels of centralization in order to further determine how a social and behaviour change approach can be used to prevent the recruitment and use of children by armed forces and armed groups.

How social and behavioural drivers influence the behaviour of armed groups

The Roots of Restraint in War study highlights how examining differences in levels of centralization is important to understanding how to influence armed forces and armed groups, and the extent to which leaders can shift group members’ behaviour depending on the level of centralization. In integrated armed forces and centralized armed groups, there is a strong chain of command where sub-commanders must follow the orders given by their senior leaders. These groups rely on clearly established rules and values.40 In comparison, decentralized and community-embedded armed groups draw to a larger extent on shared values and traditions and less on codes of conduct.41

Leaders can shift group behaviour by demanding obedience, but also by actively shaping group norms. Research on social identity shows that a leader's level of ability to influence group norms is reciprocal to group members’ perception of whether the leader is legitimate and fair.42 At the same time, other group members may influence perceived norms. They can do so especially if their public behaviour calls attention to existing norms and they thereby use their behaviour to underline compliance with the norm, or to punish another person from deviating from the norm.43 This supports the recognition that social interaction is influenced by the audience surrounding the behaviour. People may engage in different behaviour when they know others are observing; this is defined as “front stage behaviour” by Erving Goffman.44 Front stage behaviour reflects social norms and expectations for behaviour shaped partly by the context, and the role a person plays in it. It can be habitual or subconscious.45 “Backstage behaviour”, on the other hand is how people act when they are free of social expectations and norms that influence their behaviour. In other words, recruiters may engage in public or front stage behaviour that follows the group norm, whether it violates or respects IHL, while their private opinion or backstage behaviour may be different.46 As such, both social influence and private acceptance are at play in opinion change among members of armed forces and armed groups.

The ICRC's Roots of Behaviour in War study47 finds that awareness of IHL, or favourable attitudes towards it, is not sufficient to produce a direct impact on the behaviour of combatants. Instead, there seems to be a “mismatch between the knowledge combatants have of humanitarian norms and their limited inclination to respect them in the event of hostilities”.48 The divide between the knowledge of IHL and refraining from violating IHL principles happens because combatants may be acting in contradiction to their personal opinion or morality. This is defined as “moral disengagement”49 but can also be described as cognitive dissonance,50 which occurs when behavioural decisions contradict personal thoughts and attitudes. This contradiction can be linked to peer group influence or social norms. In other words, even if combatants privately think that child recruitment is wrong, they may still engage in it if their group members and leadership endorse or demand it to align with normative expectations of how they should behave. Authority figures or leaders of the group, as well as other group members/peers, may constitute a reference network for the group members. A reference network can have a heavy social influence on the behaviour of group members because the opinion of those in the network matters to the individuals in the group. The influence of the reference network can be so strong that group members may follow the norms of the group even if those norms diverge from their own individual opinions or values – i.e., front stage versus backstage behaviour as outlined above.

A combination of fear of lawful sanctions (institutional signals) and social influence can be a very impactful source of influencing behaviour.51 Accordingly, if the behaviour is linked to a social norm and the group structure is integrated or centralized, we can understand that when rules and orders are passed down through the chain of command, the combatants would comply based on the fact that (1) the message comes from their reference group and/or a leadership legitimized by the group, and (2) the combatants would have a normative expectation that other group members will also follow the chain of command. These two elements are further combined with (3) fear of sanction for not conforming to the group. In integrated armed forces or centralized armed groups, the most effective way of regulating combatant behaviour is not by influencing combatants at a personal level only but by influencing the people who have authority over them (the reference group), combined with the values of the peer/reference group to which the combatants listen because they consider that group to be credible.52 For example, social bonds of “brotherhood” in armed groups have been found to override both patriotism and ideology as an incentive to fight.53

The strong role of peer influence underlines the importance of identifying and understanding the social norms that govern armed forces and armed groups at all levels of organization. This information can be used to proactively influence integrated armed forces’ and centralized armed groups’ behaviour towards refraining from recruiting children: if commanders issue rules that prohibit the recruitment and use of children, and the group members believe that there would be social sanctions from the group if they were to recruit children, there is reason to believe that the group would refrain from doing so. In other words, by capitalizing on the group structure, values and conformity of armed forces and centralized armed groups, and influencing members of the reference group (commanders and co-combatants), combined with the fear of sanctions, it may be possible to influence what is deemed acceptable behaviour by integrated armed forces and centralized armed groups and thereby prevent child recruitment. Some experiments have also resulted in reaching the “tipping point” for norm change where the opinions of peer groups seemed to play a key role in shifting combatants’ views towards restraint.54

In focus 2: Compliance with Action Plans

One tool used to prevent the recruitment and use of children by armed forces and armed groups is the UN Security Council-mandated Action Plans. An Action Plan is negotiated between the armed actor and the UN. It follows a set structure, which outlines the prohibition of the recruitment and use of children on the basis of IHL and international human rights law. The Action Plan also includes accountability measures against those members of armed forces or armed groups who violate the Action Plan and continue to recruit and use children. Such accountability measures are dealt with internally by the armed forces or armed groups and include demotion, delayed promotion, withholding salaries or stipends, dismissal or relocation. In some cases, the violation may also lead to a legal process, e.g. the party takes the alleged perpetrator to court.

An Action Plan is typically signed by the highest military commander of the armed forces or armed group and the highest UN representative and UNICEF representative in the country. The high-level engagement in an Action Plan is crucial in order for it be accepted and followed by lower-ranking levels of armed forces or armed groups. It provides weight as the highest commander (part of the reference group for combatants) can influence the behaviour of the other members of the armed forces or armed group (lower-ranking combatants). In other words, the structure of integrated armed forces and centralized non-State armed groups can be used as a positive advantage to alter behaviour. Once an Action Plan has been signed, it is disseminated within the armed forces or armed group. The members of the group learn about and adopt the content of the Action Plan, as well as the accountability measures against those who do not comply with the Action Plan going forward. The accountability measures in the Action Plan are forward-looking.

A fixed component of an Action Plan is the establishment of a complaint mechanism to lodge individual cases of child recruitment, geared towards remedial actions. The establishment of a complaint mechanism is a strong message by the leadership of a group to its membership. It is a public signal of the commitment of the leadership to accountability to the Action Plan.

An example of how accountability measures in an Action Plan can influence an armed group's behaviour can be found in Nepal, where an Action Plan was made in the context of a nationwide disarmament, demobilization and reintegration process. During this process, former fighters, including children, were demobilized in a number of cantonment sites, followed by community-based reintegration. The commitment of the signed Action Plan applied to all components of the armed group. The progress made under the Action Plan was tracked by the UN through a monitoring system, which included a report card. The report card was populated by the UN and discussed with the leadership of the armed group. The discussions took place under the supervision of the cantonments/commanders and involved feedback to the armed group leadership on progress and bottlenecks in the implementation of the Action Plan. Progress on Action Plan implementation was more advanced for some cantonments/commanders compared to others who were lagging behind. The leadership of the armed group knew that in order to become delisted from the Secretary-General's Annual Report, every cantonment had to comply with the Action Plan. Therefore, the information shared by the UN was used by the armed group leadership to put pressure on the local commanders in the cantonments who were not delivering as expected. In this way, a combination of lawful sanction and peer group influence was used to change the behaviour of the armed groups towards refraining from the recruitment and use of children.

The example given in the “In Focus 2” box provides an example of how summary information – i.e., information about a reference group's opinion or behaviour – influenced the behaviour of armed groups through an Action Plan. In the example, information about how many IHL violations other armed groups had committed was communicated through score cards to incentivize a change in behaviour. This can also be a way of overcoming pluralistic ignorance, which occurs when individuals have factually wrong personal beliefs about prevailing social norms – for example, believing that most other armed groups recruit children, when in fact MRM statistics show that one particular group is responsible for the majority of recruitments. Decentralized and community-embedded armed groups do not always have written codes of conduct and have been found to draw more on shared values and traditions, making them more susceptible to social influence. A decentralized structure allows for a high degree of adaptability and enables “sub-group” identities that may diverge from the overall identity or ideology of the group.55 Groups from local communities may form part of an overall group, which they adhere to while having decentralized structures of command. In this context, hierarchical influence becomes more fluid and may diverge at sub-levels, while socialization and sources of group norms that influence behaviour come to the fore with respect to identifying and understanding what drives the behaviour of the group. This indicates that while integrated or centralized armed groups can to a larger extent be influenced through the higher levels of the socio-ecological framework – i.e., structures and institutional systems – the influence on decentralized and community armed groups is more fluid across the socio-ecological framework, where local levels of influence may impact across individual, interpersonal/peer, local/community, societal and national/policy levels. For example, studies in Colombia56 have found that cohesive and well-structured civilian communities can positively influence armed organizations and limit violence.

This suggests that the role of communities in limiting violence by armed groups can be leveraged to prevent recruitment and use of children. Communities’ positive and negative agency is often overlooked. Paying attention to the community level of the socio-ecological framework can advance our thinking and approach in how to leverage positive agency towards non-acceptance of the recruitment and use of children. Furthermore, informal socialization processes of peer groups – i.e., social norms upheld by the reference network – are found to have as strong an influence on behaviour as formal mechanisms such as training.57 This stresses the need to gain a better understanding of the socialization processes in armed groups and to consider ways of addressing group norms and practices that do not align with formal rules, such as child recruitment.

External sources of influence such as values, traditions, ideology or community influence58 can be enforced through individual behaviours or group summary information (see the above section on “What Is Social Norms Theory?”). In more centralized groups, hierarchical influences through institutionalized instructions and policies and lawful sanctions (institutional signals) may be more effective as tools of influence. The importance of local community, peer influence and social norms in the socialization of decentralized and community-based armed groups underlines the relevance of identifying the local drivers that influence the conduct of the group, thereby enabling us to alter that conduct. From a social and behaviour change perspective, this means that we need to leverage different levels of the socio-ecological framework depending on the level of centralization of the group in order to influence it.

In conclusion, in order to map ways to restrain violence, including child recruitment, it is necessary to understand the organizational structure, different types of authority and levels of influence of the groups concerned, as well as the networks linking key commanders and their constituencies. Using a social and behaviour change approach can enable an understanding of the inner workings of armed groups that can help us to identify these drivers of their behaviour towards violence or restraint.

Gendered impacts on the recruitment of boys and girls

As mentioned in the introduction, a key aspect to be considered in relation to armed forces and armed groups is the correlation of masculinity with the role and structure of these groups. Armed conduct is closely tied to stereotyped notions of power and manhood, and militaristic actions are supported by an ideology of male toughness.59 This can also be defining for gender roles and has key implications for which type of roles boys and girls are used for in armed groups, and in turn how boys and girls use different strategies to navigate and survive (see the following section on “The Recruited”). There are examples of centralized armed groups such as the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia – People's Army (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia – Ejército del Pueblo, FARC-EP) infusing an organizational culture that restrains certain forms of violence. Rape was against the rules of this armed group, linked to a narrative of “not who we are”;60 this shows how powerful reinforcing group norms can be in constraining certain types of behaviour. The FARC-EP specifically promoted certain norms as part of its training of recruits. The intensity of the training and who delivers it – i.e., whether the trainer is part of the combatant's reference network or not – was also found to matter.61 This showcases how integrated and centralized armed groups and armed forces may show restraint towards practices such as rape and child recruitment if interventions include hierarchical training on norms and values. It also highlights the relevance of applying a social and behaviour change approach in the organizational context to identify and understand the social and gender norms that dominate in a given group – including to identify the most effective training providers in an armed force or centralized armed group. With respect to decentralized and community-embedded armed groups, the studies in Colombia mentioned above, on how civilian communities can positively influence armed actors and limit violence, can be explored further using a social and behaviour change approach to map the positive community influences to be leveraged, including any social and gender norms that may be at play.

Understanding how the concept of masculinity impacts on the governance of both centralized and decentralized armed groups, by including a gender analysis, is essential to explaining the differing experiences of recruited boys and girls (this is explored further in the following section). A gender analysis62 systematically unpacks the drivers of prevailing gender norms and power relations in a specific context and unveils different roles and norms for women and men, girls and boys, in the distribution of power, status, decision-making, resources, needs, opportunities and constraints. It also explores how gender intersects with age, race, disability, culture, ethnicity and/or other status. This knowledge is critical to preventing transition processes that may attempt to reconstruct the patriarchal, legal, social and cultural institutions which existed pre-conflict, instead of capitalizing on the opportunity to redefine them and avoid a continued cycle of violence.63 This is important for prevention efforts with respect to understanding how the armed group operates, and for reintegration, reconciliation and peacebuilding efforts, which may provide the chance to change social and gender norms towards more equal and less violent societies.

The recruited: Boys and girls recruited and used by armed forces or armed groups

In this section we turn our focus to the core of the socio-ecological model: the children. In order to prevent and respond to child recruitment, it is crucial to understand why boys and girls join armed forces or armed groups. A United Nations University (UNU) study has identified a list of prosocial motivations that may influence children's agency to either join or stay with an armed actor; these are summarized in Table 1.

Factors that may drive children to join armed groups

| A need and wish to belong | Everybody wants to belong, and both boys and girls, particularly adolescents, struggle with belonging and identity. Armed forces and armed groups provide a ready-made community and identity through which children may get to feel a purpose, and these are elements that may be even more attractive in situations of insecurity and danger. |

| Quest for significance | We all have a desire to feel a purpose in life, and armed forces and armed groups may capitalize on this “quest for significance”, including by taking advantage of feelings of insignificance that children may have experienced elsewhere. |

| Peer networks | Peers can have a strong influence on behaviour through role-modelling and/or reinforcing prevailing social norms. The effects of peer influence can be even stronger when combined with a need to belong. |

| Risk accumulation | Social risk factors found to increase children's probability of joining armed groups include exposure to violence, separation from family, poverty and other negative life events. |

| Impulsive behaviour | It is more common for children than for adults to display impulsiveness and risk-seeking behaviour when they are in the presence of their peers. Impulsive behaviour and risk-taking are also linked to the level of development of the brain in children and adolescents, which makes them less able to control their behaviour, especially in social and emotional situations.64 |

| Bucking authority | Children may join armed groups because it gives them a sense of power and an opportunity to assert their autonomy. In addition, they may react against figures of authority who they feel threaten their agency. |

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on Rebecca Littman, Children and Extreme Violence: Insights from Social Science on Child Trajectories Into and Out of Non-State Armed Groups, United Nations University, New York, 2017.

These prosocial motivations may increase children's vulnerability to recruitment and use by armed organizations and are likely to differ for some children compared to others, which highlights the individual nature of children's trajectories into armed organizations. In addition, factors in the surrounding environment such as armed conflict, poverty,65 climate change,66 economic impacts,67 education and employment opportunities may also contribute to boys’ and girls’ decisions to join armed organizations.68

Although the focus here is on prosocial motivations, it is important to note that these factors do not operate in isolation. Linked to the prosocial motivations highlighted in Table 1, three key factors should be taken into consideration when seeking to identify social and behavioural drivers from the perspective of recruited children: agency, age and gender.

It is important to acknowledge boys’ and girls’ agency in their association. The debate as to whether children can be considered to have joined an armed actor voluntarily is ongoing.69 However, to consider boys and girls as involuntarily recruited without any agency could undermine their prospects for reintegration. For some boys and girls, the time spent with an armed actor includes aspects of learning, growth and a sense of empowerment or bucking authority as described by the UNU study. This could include a strengthened understanding of structure and hierarchy and a feeling of belonging and comradery. To dismiss these aspects of children's experience by default and deny their agency could impact their capacity to reintegrate by failing to understand their trajectory, which in turn will make it difficult to tailor an effective response.70 For recruited children, there is no linear trajectory from victim to perpetrator; instead, children are situated in a grey zone of being both victim and perpetrator.71 Regardless of the nature of the association, however, the Paris Principles state that boys and girls engaged with armed forces or armed groups should primarily be understood as victims of offences against international law and not as perpetrators.

As we saw from the UNU study, the possible prosocial motivations for children's association with armed forces and armed groups resonate with the formative years of adolescence:72 the need to belong, the quest for significance, peer networks and impulsive behaviours. The age and agency dynamics play a particular role for adolescents as they are exploring who they are and who they want to become, which requires not only room for decision-making but also an environment that helps and guides them in taking those decisions. They are more likely to make risky choices with short-term benefits, which could have significant consequences if a child joins armed forces or an armed group. Impulsive behaviours make children even more sensitive to social sanctions, which makes it easier for armed forces or armed groups to strategically influence their behaviour by exposing them to social and gender norms and behaviours that endorse violence. Armed groups often encourage violent behaviour, and this may lead group members, particularly adolescents and children who are keen to adopt group norms, to perceive violence as behaviour that is wanted and desirable by the group. Importantly, this belief does not necessarily mean that the child has a personal desire to engage in violent behaviour.73 Children might conform to violent behaviour based on a normative expectation that this is what is expected from them by the group, combined with social reward rather than sanction.

The experience of boys and girls is likely to differ based on social and gender norms.74 For girls, gender inequality and gender roles often reflect the risks they may face during their association, including sexual exploitation and/or being used as housekeepers, cooks, and to look after children of combatants belonging to the armed forces or armed groups.75 The risk of gender-based violence may also be a driver for girls’ association. Girls may join armed groups to break free from social norms limiting their freedom and to avoid gender-based violence, including child marriage. A study from Jordan found that drivers of women's and girls’ engagement in groups practicing extreme violence were linked to social and family problems, including domestic violence and prevention of their access to rights such as inheritance.76 Physical, emotional and sexual abuse within families have also been cited by girls and women in Colombia as a reason for their association with armed organizations.77 Girls may also be recruited for combatant roles. One example of this is the force known as the Kurdish People's Protection Units in northeast Syria, which includes an all-female militia called the Women's Protection Units (Yekîneyên Parastina Jin, YPJ).78 The UN has verified over 150 girls recruited by Kurdish armed groups since 2013 and several of these girls were in combat roles, armed and in uniforms, for example while guarding checkpoints.79 For some of these girls, the drivers for their recruitment included the possibility of escaping traditional gender roles and discrimination such as child marriage and domestic violence,80 as well as ideology and financial aspects.81

Gender norms do not only impact girls’ experiences with armed forces or armed groups. Prevalent gender norms dictating boys’ behaviour are equally destructive. Concepts around masculinity, power, pride and honour, as well as the perception of boys and men as protectors and breadwinners and as being inherently more violent than girls and women, may contribute to boys’ engagement with armed forces and armed groups.82 Additionally, as described in the above section on “The Recruiters”, meta-norms such as hyper- or toxic masculinity may often dominate the governance and hierarchy of armed forces and armed groups. While it is beyond the scope of this article to further unpack this, gender is and must be a critical part of the analysis of social and behavioural drivers of child recruitment.83 The Communities Care Programme in Somalia is an example of programming that has contributed to shifting harmful social norms that contribute to sexual violence into positive social norms that promote women's and girls’ equality, safety and dignity.84

In focus 3: Girls and reintegration efforts

Failing to acknowledge the specific vulnerabilities and experiences of girls has resulted in girls falling between the cracks in release and reintegration efforts. For example, lessons learned from disarmament, demobilization and reintegration (DDR) programmes indicate that girls were less likely to be released because the definition used were influenced by gender norms. A key criterion for accessing DDR services has been the possession of a weapon and the ability to assemble and disassemble it. Girls, who in many instances were in support roles such as cooks, porters, “wives” or informants, rarely carried weapons and were thus overlooked.85

A social and behavioural change perspective would consider social and gender norms and/or behavioural drivers that enabled the recruitment of children and include those aspects in the DDR programme design. For example, association with armed forces or armed groups may come with significant stigma, especially for girls in the reintegration process. There are often assumptions building on prevailing gender norms, which reflect how girls are valued or devalued in society. They may be devalued if they have lost their virginity. If they have given birth to a child with a father from the “enemy”, this can lead to further rejection from the family and community. It may also be difficult for girls who had leadership or combat roles to adapt back into the traditional gender-stereotyped expectations which may prevail in the community that they come from.86

The protective environment

Addressing some of the potential drivers described in the preceding sections requires the involvement of parents/caregivers, peers and communities. These are the closest spheres of influence and protection, but they may also be the drivers for children's association with armed organizations.87

Communities

Through community engagement, awareness-raising and parenting support, it is possible to tap into and build the protective sphere around children. As seen in the above section on “The Recruiters”, communities can play a decisive role in limiting violence by armed forces and armed groups by employing a range of different strategies. This indicates that cohesive communities can play a key role in preventing recruitment and use of children. While each group will need to be analyzed and addressed with specific interventions, the community leadership, specific community members, youth leaders, religious leaders and family members may all play individually and collectively important roles in preventing and dissuading children from joining armed organizations. As such, it is equally important to map community practices that protect boys and girls from harm. Mapping these community strategies can be a starting point for engaging with communities on the prevention of child recruitment and can inform broader prevention strategies.

Parents/caregivers

In its study on children's involvement with armed groups,88 the UNU also explores the family as a driver for children's association with armed groups. One cited study from the International Labour Organization's International Labour Office explores the experience of youth who had joined armed groups in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. This study reveals that the difference between the formerly recruited youth and their peers who had not joined armed groups was in fact that the formerly recruited youth also had relatives who belonged to the armed group.89 In the cited study, 57% of surveyed youths who had joined an armed group had a father or brother who also belonged to an armed group.90 Parents and families may also encourage their children's association with armed groups, as in Rwanda, where parents of children formerly associated with an armed group spoke proudly about how they had instigated their children's association.91

In order to understand and address the root causes of these attitudes and behaviours, it is crucial to unpack the drivers behind them. A decisive factor for a child becoming more vulnerable to recruitment may be a social norm that child involvement in armed conflict is accepted, which in turn may make parents susceptible to letting their children join armed groups, given normative expectations – i.e., they think this is what their reference group (the community) thinks they should do, and they worry about sanctions if they keep their child home. In conflict contexts, communities may become accustomed to the presence of conflict, making it a new “normal”, but this doesn't necessarily mean that a positive norm towards child recruitment has been established. The combination of immense environmental stressors caused by conflict, food scarcity and economic hardship may push community members to “allow” children's association with armed organizations to continue, while they do not personally agree with the practice. Anecdotal evidence from practitioners tells us that in households that have no actual choice in letting children join or not, and where a child is recruited against the family's will, it may lead to excessive guilt. This can create cognitive dissonance where, in order to cope, the family creates beliefs built on justifications for giving in to the pressure of the armed group in order to reduce the dissonance between what they think and what they do/did.

The UNU study also mentions family violence, domestic violence and oppressive family environments as factors for understanding boys’ and girls’ trajectories into armed organizations.92 As stated earlier, girls may join armed organizations to avoid domestic and sexual violence. For example, in Nepal, girls have stated that they joined the Maoists to avoid abusive or arranged marriages.93 Girls in northeast Syria also cited early marriage as a reason for joining armed organizations.94

Peers

As illustrated in the above section on “The Recruited”, adolescents appear to be particularly vulnerable to recruitment and use. When children enter adolescence, peers often become more influential compared to earlier in their lives, when parents/caregivers and other family members may have played the more important role. According to child psychology studies, adolescents’ exposure to deviant peers can be linked to an increase in delinquent behaviours.95 Similar to family members, peers can have an influence on children's trajectories with armed groups; studies from Nigeria, Jordan and Somalia show how peers influenced children's association with such groups.96 Therefore, understanding peer influence is a key component in the mix of drivers that may lead children to join armed organizations.

The behaviours and attitudes of the actors in the inner circles of the socio-ecological framework can become drivers of boys’ and girls’ association with armed groups and armed forces, but they also make up children's most important safety net. There are good examples and evidence of working with families, peers and community members using social and behaviour change strategies to prevent and respond to child protection concerns such as female genital mutilation and child marriage.97 There is also a growing body of evidence and tools relating to parenting programmes98 for violence prevention built on social and behaviour change strategies.

Importantly, efforts in the inner circles of the socio-ecological framework must be linked to the outer circles as well – i.e., the institutional and policy level. Local and national authorities, education and social protection systems, laws and legislation etc. must be leveraged to address structural and institutional factors that may constitute drivers of child recruitment, such as lack of access to school and the absence of inheritance rights for women. As per the behavioural drivers model, structural factors form part of the drivers that influence behaviour and must therefore form part of the analysis of drivers of child recruitment. A newly released programme development toolkit on prevention and reintegration of children associated with armed forces and armed groups (CAAFAG) also examines risk factors across the socio-ecological framework and illustrates how these play a key role in addressing child recruitment.99 Additionally, it refers to how social and cultural norms may have a significant impact on the prevention of recruitment and highlights the need to influence these through transformative programmes as part of prevention strategies.100

Putting it all together: How can a social and behaviour change approach inform prevention and reintegration programming?

With reference to the previous sections, for a social and behaviour change approach to be effective in prevention and reintegration programming, it is necessary to understand the social norms and behaviours of the different groups involved (the recruiters, the recruited and the protective environment).

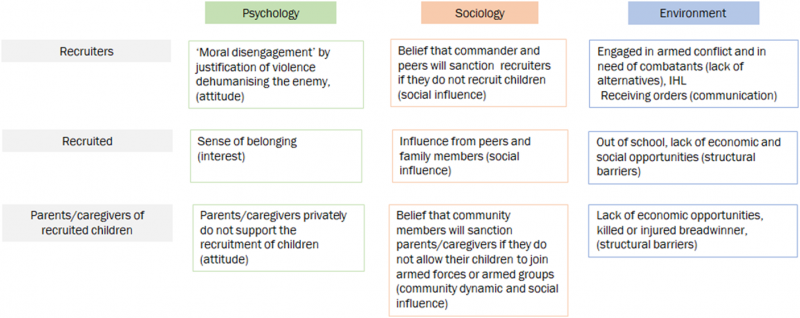

Figure 3 uses concepts from the behavioural drivers model and exemplifies how the behaviour of the recruiters, the recruited, and parents/caregivers (as part of the protective environment) of the recruited may be influenced by drivers of psychological, sociological and environmental character in a context of child recruitment.

A social and behaviour change approach can inform prevention and reintegration efforts as well as enabling a response that bridges the humanitarian, development and peace nexus. Changing behaviours requires long-term investment and engagement, but it will help to prevent the behaviours enabling child recruitment to grow among children, families, communities, armed forces and armed groups, governing institutions, and authorities, impeding it from becoming a social norm across the concentric circles of the socio-ecological framework. In other words, using a social and behavioural change approach can inform prevention and reintegration programming because it helps to answer the question of why children are recruited from the perspective of the key actors and entities across the socio-ecological framework. If we know the behavioural drivers behind child recruitment, we can better apply the most effective programmatic interventions to prevent it from happening in the first place.

The examples below illustrate how findings and interventions can be coupled for each of the groups examined (the recruiters, the recruited and the protective environment), mindful that all relevant factors driving a given behaviour would need to be addressed for each group in order for the interventions to be effective.

With reference to the behavioural drivers model shown in Figure 2, formative research may identify social influence, self-efficacy and community dynamic as having a key influence on the practice of child recruitment. This means it would be necessary to build our programming with a focus on these drivers.

-

At the level of the recruiters, social influence may be found to be a key factor driving armed forces or armed groups to recruit children. The formative research may find that attitudes and practices of the peer group (reference network), combined with fear of stigma, are the key dimensions of social influence driving armed forces or armed groups to recruit children. As highlighted by the ICRC studies mentioned earlier, recruiters may overrule their own private opinions in order to comply with the group behaviour. In that case our interventions would need to address social influence, for example through engaging commanders to make commitments through Action Plans, and a positive deviance/group summary information approach as exemplified in the “In Focus 2” box above, combined with influencing the social identity of the group.

-

At the level of the recruited children, self-efficacy may be found as a key factor; the formative research may find that lack of a sense of belonging, skills and confidence are key dimensions or push factors that cause children to join armed forces or armed groups. These would need to be addressed in order to provide the children with alternatives to recruitment. Access to education and life skills training combined with psychosocial support may provide for increased self-efficacy and sense of belonging and contribute to making children more resilient to recruitment.

-

At the level of communities, formative research may identify dimensions of community dynamics that can be used as entry points to work with community cohesion and authority in order to disincentivize armed forces and armed groups with respect to the recruitment and use of children – especially if recruiting children would cause sanctions affecting the ability of the armed group to maintain its presence and leverage traditional community structures or distribution of power, in the case of decentralized or community-embedded armed groups.

-

At the level of parents/caregivers, the formative research may find that structural barriers linked to economic difficulties are a push factor causing parents/caregivers to let their children join armed forces or armed groups. Here, cash transfer programmes could be considered to help families keep their children at home and in school.

-

At the level of peers, the formative research might find that dimensions of interest – i.e., peer group pressure combined with wanting to belong to a group – are factors that may deem it more likely for children to join armed groups. To create a positive alternative, establishing youth clubs and fostering dialogue among peers about the challenges they face in their daily lives and the risks of joining armed groups may help children to obtain peer support that will make them more resilient against joining armed groups.

Longer-term engagement can be bridged by integrating child protection efforts across programming dimensions and sectors, including education, health and gender, in order to leverage these in prevention and response strategies for child recruitment. The contextual drivers of child recruitment and their negative impact on children cannot be significantly controlled and influenced by one sector alone. These drivers include deeply rooted poverty and mistrust in institutions; limited offers of critical opportunities such as free, compulsory schooling; inadequate livelihoods for households; impunity of child recruiters and operating modalities by the security sector that conflict with the best interests of the child; social and gender norms driving the normalization of weapons; negative masculinity; and the use of violence to meet political or security needs. As such, prevention and reintegration requires a multisectoral response. This article suggests that such a response can be better leveraged through a social and behaviour change approach.

Conclusion

The authors of this paper see great potential in using social and behaviour change strategies to help prevent and respond to the recruitment and use of boys and girls by armed forces and armed groups. If we do not tackle the social and gender norms and behaviours enabling child recruitment, they may continue to grow and become more accepted across the socio-ecological framework. Using social and behaviour change approaches can inform prevention and reintegration programming because it helps to answer the question of why children are recruited from the perspective of the key actors and entities across the socio-ecological framework. While we do not yet have all the answers, this article has aimed to provide some pieces of the puzzle on how to apply the social and behaviour change approach to address child recruitment. We hope that this article will serve as inspiration for further reflection and discussion on developing evidence-based social and behaviour change interventions to end the recruitment and use of boys and girls in armed conflict.

- 1Andrea C. Johnson et al., “Qualitative Evaluation of the Saleema Campaign to Eliminate Female Genital Mutilation and Cutting in Sudan”, Reproductive Health, Vol. 5, 208, available at: https://reproductive-health-journal.biomedcentral.com/articles/0.86/s29… (all internet references were accessed in August 2023); Grandmother Project, available at: https://grandmotherproject.org/; Kate Doyle et al., “Gender-Transformative Bandebereho Couples Intervention to Promote Male Engagement in Reproductive and Maternal Health and Violence Prevention in Rwanda: Findings from a Randomized Controlled Trial”, PLoS ONE, Vol. 3, No. 4, 208, available at: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=0.37/journal.pone.092756; Tanya Abramsky et al., “Findings from the SASA! Study: A Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial to Assess the Impact of a Community Mobilization Intervention to Prevent Violence against Women and Reduce HIV Risk in Kampala, Uganda”, BMC Medicine, Vol. 2, No. 22, 204, available at: https://bmcmedicine.biomedcentral.com/articles/0.86/s296-04-022-5; Save the Children, Choices, Voices, and Promises: Empowering Very Young Adolescents to form Pro-Social Gender Norms as a Route to Decrease Gender Based Violence and Increased Girls’ Empowerment, 205.

- 2Alliance for Child Protection in Humanitarian Action, CAAFAG Programme Development Toolkit: Training Guide and Guidelines, 0, available at: https://alliancecpha.org/sites/default/files/technical/attachments/caaf….

- 3This paper uses the definition of a child from the Convention on the Rights of the Child: a child means every human being below the age of 18 years.

- 4United Nations, United Nations Secretary-General Guidance Note on Behavioural Science, 2021, available at: www.un.org/en/content/behaviouralscience/.

- 5As an example of formative research in this area, UNICEF Lebanon conducted a study in 2020 to identify drivers of violence, including the recruitment and use of children, which exemplifies the type of data collection needed: UNICEF, Underneath the Surface: Understanding the Root Causes of Violence against Children and Women in Lebanon, Beirut, 2020, available at: www.unicef.org/lebanon/reports/understanding-root-causes-violence-again…. See also Noriko Izumi and Line Baagø-Rasmussen, “The Multi-Country Study on the Drivers of Violence Affecting Children in Zimbabwe: Using a Mixed Methods, Multi-Stakeholder Approach to Discover What Drives Violence”, Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies, Vol. 13, Supp. 1, 2018.

- 6Graça Machel, Impact of Armed Conflict on Children, UN General Assembly, 199, available at: https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N9/219/55/PDF/N921955.pdf….

- 7The Paris Principles: Principles and Guidelines on Children Associated with Armed Forces and Armed Groups, 200, available at: www.unicef.org/mali/media/1561/file/ParisPrinciples.pdf.

- 8Ibid.

- 9The prohibition is stipulated in the 177 Additional Protocols to the Geneva Conventions and in the 18 Convention on the Rights of the Child.

- 10Office of the UN Special Representative of the Secretary-General for Children and Armed Conflict, The Six Grave Violations against Children during Armed Conflict: The Legal Foundation, New York, 2013, available at: https://childrenandarmedconflict.un.org/publications/WorkingPaper-1_Six….

- 11African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child, 1990, available at: https://au.int/sites/default/files/treaties/36804-treaty-african_charte….

- 12United Nations, Children and Armed Conflict: Report of the Secretary-General, UN Doc. A/77/895-S/2023/363, New York, 2023, available at: https://daccess-ods.un.org/access.nsf/Get?OpenAgent&DS=S/2023/363&Lang=E.

- 13Ibid.

- 14See, for example, Marco C. Yzer et al., “The Role of Distal Variables in Behavior Change: Effects of Adolescents’ Risk for Marijuana Use on Intention to Use Marijuana”, Journal of Applied Social Psychology, Vol. 34, No. 6, 2003, Fig. 1, available at: www.researchgate.net/figure/An-integrative-model-of-behavioral-predicti…; Howard Leventhal, S. Stephen Kegeles, Godfrey Hochbaum and Irwin Rosenstock, “Health Belief Model”, available at: www.besci.org/models/health-belief-model; Social Change UK, “The COM- B Model of Behaviour”, London, 2019, available at: https://social-change.co.uk/files/02.09.19_COM-B_and_changing_behaviour….

- 15See Jill. F. Kilanowski, “Breadth of the Socio-Ecological Model”, Journal of Agromedicine, Vol. 22, No. 4, 2017, pp. 295–297.

- 16See Vincent Petit, The Behavioural Drivers Model: A Conceptual Framework for Social and Behaviour Change Programming, UNICEF, 2019.

- 17Beniamino Cislaghi and Lori Heise, “Four Avenues of Normative Influence: A Research Agenda for Health Promotion in Low and Mid-Income Countries”, Health Psychology, Vol. 37, No. 6, 2018.

- 18Vincent Petit and Tamar Zalk, Everybody Wants to Belong: A Practical Guide to Tackling and Leveraging Social Norms in Behaviour Change Programming, UNICEF and University of Pennsylvania Social Norms Group, 2019.

- 19Beniamino Cislaghi and Lori Heise, “Gender Norms and Social Norms: Differences, Similarities and Why They Matter in Prevention Science”, Sociology of Health and Illness, Vol. 42, No. 2, 2020.

- 20Ibid.

- 21Deborah A. Prentice, “The Psychology of Social Norms and the Promotion of Human Rights”, in Ryan Goodman, Derek Jinks and Andrew K. Woods (eds), Understanding Social Action, Promoting Human Rights, Oxford University Press, New York, 2012, Chap. 2.

- 22Ibid.

- 23Cristina Bicchieri, Norms in the Wild: How to Diagnose, Measure, and Change Social Norms, Oxford University Press, New York, 2016; V. Petit and T. Zalk, above note 18.

- 24Various tools are available for guidance on diagnosing social norms. See, for example, Cait Davin et al., Social Norms Exploration Tool, Social Norms Learning Collaborative, Institute for Reproductive Health, 2020, available at: www.alignplatform.org/resources/social-norms-exploration-tool-snet; Leigh Stefanik and Theresa Hwang, Applying Theory to Practice: CARE's Journey Piloting Social Norms Measures for Gender Programming, CARE USA, 2017, available at: www.alignplatform.org/resources/applying-theory-practice-cares-journey-…; C. Bicchieri, above note 23; Cait Davin et al., Getting Practical: Integrating Social Norms into Social and Behaviour Change Programs, Social Norms Learning Collaborative, Breakthrough ACTION, Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs, 2021, available at: https://breakthroughactionandresearch.org/getting-practical-tool/.

- 25D. A. Prentice, above note 21.

- 26Margaret E. Tankard and Elisabeth Levy Paluck, “Norm Perception as a Vehicle for Social Change”, Social Issues and Policy Review, Vol. 10, No. 1, 2016.

- 27Ibid.

- 28For more information, see Alliance for Child Protection in Humanitarian Action, “Standard 14: Applying a Socio-Ecological Approach to Child Protection Programming”, in Minimum Standards for Child Protection in Humanitarian Action, 2023, available at: https://handbook.spherestandards.org/en/cpms/#ch006_002.

- 29V. Petit and T. Zalk, above note 18.

- 30For a detailed explanation and definition of these terms and how they can be applied, see V. Petit, above note 16.

- 31The MRM is a UN Security Council-mandated mechanism (Resolution 1612) which enables the UN to monitor, document and verify grave violations against children in armed conflict. There are six grave violations: killing and maiming of children, recruitment and use of children, sexual violence against children, abduction of children, attacks against schools and hospitals, and denial of humanitarian access for children. Only incidents that are verified through primary sources (e.g. interviewing the child survivor or a primary witness to the violation such as a caregiver or first responder) are considered verified according to the MRM methodology. This means that the verification standard is set high and offers lots of detail, but it also means that the MRM by default cannot capture the full scope of grave violations against children; it can only claim to capture the tip of the iceberg. However, the richness of the data is used to draw trends and see patterns of violations against children in situations of armed conflict.

- 32See overview of tools from different organizations through the Social Norms Learning Collaborative and ALIGN, available at: www.alignplatform.org/tools-identifying-diagnosing-social-and-gender-no…; and overview of social and behaviour change programming guides for different sectors, available at: www.thecompassforsbc.org/multi-sbc/search.

- 33For more information, see Alliance for Child Protection in Humanitarian Action, above note 28.

- 34For examples of formative research, see above note 5.

- 35These groups are what the authors believe to be the main networks relevant in cases of child recruitment. We do not exclude other groups that may be of importance but have chosen to limit focus to these for the purposes of this paper. We also acknowledge that they may in many instances overlap with each other.

- 36For the purpose of this paper, we are focusing on how to identify the reasons why armed forces or armed groups recruit children – the reasons are many and will differ from context to context. Evidence shows that children are recruited and used for various purposes and on various grounds. It may be the case that there is a utility in using children – e.g., children replace adults because fighting-age males are not available – or that children are more easily manipulated compared to adults due to their underdeveloped sense of right and wrong and are therefore targeted for recruitment by armed groups. See Siobhan O'Neil and Kato van Broeckhoven, Cradled by Conflict: Child Involvement with Armed Groups in Contemporary Conflict, United Nations University, Tokyo, 2018, pp. 45–47.

- 37D. A. Prentice, above note 21.

- 38Daniel Muñoz-Rojas and Jean-Jacques Frésard, The Roots of Behaviour in War: Understanding and Preventing IHL Violations, ICRC, Geneva, 2004.

- 39Fiona Terry and Brian McQuinn, The Roots of Restraint in War, ICRC, Geneva, 2018.

- 40Ibid., p. 23.

- 41Ibid., pp. 46–47.

- 42M. E. Tankard and E. L. Paluck, in above note 26.

- 43Ibid.

- 44Erving Goffman, The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life, Overlook Books, 1974.

- 45Nicki Lisa Cole, “Goffman's Front Stage and Back Stage Behavior”, ThoughtCo, 2021, available at: www.thoughtco.com/goffmans-front-stage-and-back-stage-behavior-4087971.

- 46Solomon E. Asch, “Opinions and Social Pressure”, Scientific American, Vol. 193, No. 5, 1955; Solomon E. Asch, “Effects of Group Pressure upon the Modification and Distortion of Judgments”, in Harold Steere Guetzkow (ed.), Groups, Leadership, and Men: Research in Human Relations, Russell & Russell, New York, 1951.

- 47D. Muñoz-Rojas and J.-J. Frésard, above note 38.

- 48Ibid., p. 8.

- 49The ICRC study identifies two key elements that cause “moral disengagement”: (1) Justification of violations. The perpetrators see themselves as victims who need to act against the enemy before the enemy acts against them. They believe they are fighting an honourable cause while the opposing side is fighting for inadmissible interests that only deserve condemnation. If the enemy is guilty or suspected of violations of IHL, opposing combatants will argue that they are justified in not respecting it either, invoking a universal argument of reciprocity to justify their behaviour. (2) Dehumanizing the enemy. This relates to the psychology of the perpetrator and may involve demonizing the enemy to justify excessive means to an end, and denying, minimizing or ignoring the consequences of using excessive means by attribution of blame to the victim. Ibid., pp. 8 ff.

- 50Leon Festinger, A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance, Stanford University Press, Stanford, CA, 1957.

- 51F. Terry and B. McQuinn, above note 39.

- 52Ibid.

- 53Ibid., p. 30.

- 54Ibid., p. 31.

- 55Ibid.

- 56Ibid., pp. 42–43.

- 57Ibid.

- 58Ibid.

- 59Dina Francesca Haynes, Fionnuala D. Ní Aoláin and Naomi R. Cahn, “Masculinities and Child Soldiers in Post-Conflict Societies”, in Frank Cooper and Ann McGinley (eds), Masculinities and Law: A Multidimensional Approach, Minnesota Legal Studies Research Paper No. 10-57, 2011.

- 60F. Terry and B. McQuinn, above note 39, pp. 39–43.

- 61Ibid.

- 62For information and resources on gender analysis, see, for example, Jhpiego, “Gender Analysis Toolkit for Health Systems: Gender Analysis”, available at: https://gender.jhpiego.org/analysistoolkit/gender-analysis/; Government of Canada, “What Is Gender Analysis?”, available at: www.international.gc.ca/world-monde/funding-financement/gender_analysis….

- 63D. F. Haynes, F. D. Ní Aoláin and N. R. Cahn, above note 59.

- 64Rotem Leshem, “Brain Development, Impulsivity, Risky Decision Making, and Cognitive Control: Integrating Cognitive and Socioemotional Processes during Adolescence – An Introduction to the Special Issue”, Journal of Developmental Neuropsychology, Vol. 41, No. 1–2, 2016.