Delivering water services during protracted armed conflicts: How development agencies can overcome barriers to collaboration with humanitarian actors

Introduction: Development and protracted armed conflict

Armed conflicts remain the biggest challenge for human development and poverty eradication efforts.1 At the time of writing, 2 billion people live in countries where development outcomes are affected by fragility, conflict and violence, and more than 65 million people are forcibly displaced because of armed conflicts whose protracted nature also prevents many from returning to their homes.2 If the current trends persist, by 2030 half of the world's poor will live in contexts affected by violence and conflict, rising from 20% today.3

Conflicts prevented many countries from reaching the Millennium Development Goal (MDG) targets. The MDGs were defined in 2000 by world leaders gathered at the United Nations (UN) as a set of eight international development goals (and twenty-one targets) focused on tackling poverty and hunger, disease, gender inequality and environmental sustainability.4 Analysis of progress towards the MDGs shows that countries affected by fragility, conflict and violence had the highest proportion of MDGs not achieved, with most such countries only achieving two out of the twenty-one targets.5 Conflicts can also reverse hard-won development gains, confirming the maxim that conflict is essentially development in reverse.6 Contexts affected by armed conflicts will also face the greatest hurdles in progressing towards the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which replaced the MDGs in 2015. The SDGs are a global agenda that commits all countries to work towards a peaceful and resilient world by addressing a set of seventeen integrated goals, which range from eradicating poverty (SDG 1) and reducing inequality (SDG 10) to providing clean water and sanitation (SDG 6) and peace, justice and strong institutions (SDG 16). Compared to the MDGs, the SDGs present a much wider and ambitious set of targets, which will require significant efforts in order to be achieved.7

Protracted armed conflicts pose particular challenges to development because of their characteristics. First, these conflicts are characterized by longevity, intractability and mutability.8 Second, protracted armed conflicts are also characterized by cumulative impacts on water infrastructure and institutions; these impacts compromise, among other things, the ability of national and local authorities to provide basic water services,9 which are a key enabler of development interventions. Finally, protracted armed conflicts are characterized by volatile aid flows. This latter characteristic is particularly relevant for the work of development agencies, as in high-risk contexts volatile aid flows can amplify existing instabilities and constrain the capacity for post-conflict recovery.10

Protracted armed conflicts can also have significant spillover effects beyond the countries directly affected, dramatically impacting the stability, development gains and economic prospects of neighbouring countries and beyond. For instance, the still ongoing war in Syria has not only caused devastating human suffering (between 400,000 and 470,000 estimated deaths, and more than 12 million forcibly displaced) and economic damage ($226 billion from 2011 to 2016) in the country, but has also affected the neighbouring countries of Turkey, Lebanon, Jordan, Iraq and Egypt.11 The cost to these five countries is close to $35 billion in output, equivalent to Syria's GDP in 2007 (measured in 2007 prices).12 In Jordan alone, the World Bank estimates the cost of hosting Syrian refugees at about $2.5 billion a year, equivalent to 6% of GDP and a quarter of the government's annual revenues.13

The far-reaching impacts of protracted armed conflicts on development outcomes raise important questions for development actors. In order to achieve poverty reduction and sustainable development objectives, development actors need to revise their approach for engaging during protracted armed conflicts and step up their collaboration with humanitarian agencies and governments in these settings.14 With the goal of alleviating human suffering and not undermining the basis for human development efforts, development actors are increasingly working to reduce vulnerabilities to shocks, address the underlying causes of protracted armed conflict, and meet humanitarian needs. Recent international commitments, including the Paris Declaration (2005), the Accra Agenda for Action (2008)15 and the new deal for engagement in fragile states (2011) have emphasized the role that development actors and development assistance can play in countries affected by conflict and violence.16 The recently adopted SDG 16 also recognizes the importance of ending violence and encouraging the rule of law to support the global sustainable development agenda, specifically aiming to reduce all forms of violence (Target 16.1), particularly against children (Target 16.2), and to promote the rule of law (Target 16.3).17

However, inasmuch as development agencies are increasingly willing to engage in contexts experiencing protracted armed conflicts, several barriers to successful engagement remain. This note examines some of the barriers that affect the ability of development actors to successfully bridge the development–humanitarian divide before, during and after protracted armed conflicts. Systematically examining and organizing these barriers can serve to advance understanding of the issues for both development and humanitarian actors. Using the water sector as an example, the note presents the experience of the World Bank – one of the world's largest sources of funding for development – in trying to overcome some of the barriers. The primary goal of this note is (1) to advance the discussion on the barriers that prevent more successful and effective interaction between development and humanitarian actors, and (2) to describe some of the World Bank's experiences related to water service delivery and the ways in which it has tried to overcome these barriers, as examples of good practice for development and relief efforts. The note provides a personal perspective on some aspects of humanitarian and development work and the links between them; hence, it is not intended to provide a thorough and comprehensive review of the literature on the humanitarian–development interface.

Defining development and humanitarian work

This section defines the terms “development” and “humanitarian” in the context of a protracted armed conflict. The objectives and activities that characterize development and humanitarian work are discussed, highlighting some of the differences and complementarities. Recognizing the complexities around the definitions of humanitarian and development work, this section makes reference to specific cases and organizations rather than trying to provide a comprehensive review of the conceptual differences between the two sectors, which is outside the scope of this note. Based on the author's experience, development work is described from the point of view of the World Bank, and only humanitarian organizations with which the World Bank has collaborated in the past or is collaborating at the time of writing are considered (some UN agencies and the components of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement (the Movement)).

The key message from this section is that development and humanitarian interventions have different objectives and that there is limited overlap between these objectives. Although development work will ultimately contribute to improving conditions and living standards for humanity, thus converging with humanitarian objectives, it usually does not have as its only focus saving lives and reducing suffering, which is the purpose of humanitarian action.18 This difference should not prevent development and humanitarian actors from working together; however, it should be acknowledged and carefully considered in order for development and humanitarian actors to align their work and avoid undermining each other.

The development approach

Development actors appraise their interventions based on concepts such as poverty reduction, economic opportunity, resource use sustainability and cost-effectiveness.19 A development approach recognizes the centrality of country institutions (national and local governments) to both implement and sustain interventions. A development approach is based on the premise that the beneficiaries of these interventions directly manage the assets created, or that the assets are managed by country institutions.20 Increasingly, development actors recognize the importance of addressing issues such as social justice, accountability, political stability and climate change when working with developing countries to reduce poverty.21

Development actors focus their work on constructing long-term relationships with government stakeholders and representatives from civil society and the private sector in order to build institutions and to promote strategic agendas and projects, including social and economic reforms as well as major infrastructure. This type of relationship and focus constrains international development actors in their ability to engage in situations where there is rapid decline in institutional integrity and capacity. As well as the deterioration of policy and institutional indices being linked to shrinking financing envelopes, financing often has to be suspended when country institutions are unable to demonstrate the required levels of fiduciary control.22 At early signs of risk and in fragile contexts, these constraints often limit the scope for development programming to address causes of tension.23

The World Bank is one of the world's largest sources of funding and knowledge for development. The World Bank finances its programmes via capital markets and by receiving contributions from member governments in donor countries. The World Bank is best known for its financial services, consisting of loans to client countries. The terms of the loans differ depending on the client country's eligibility. The investment lending provides financing for a range of activities aimed at creating the social (capacity, institutions) and physical (roads, dams) infrastructure needed to eradicate extreme poverty and achieve sustainable development.

Work in post-war areas is one of the core businesses of the World Bank, exemplified in Article I of the World Bank's Articles of Agreement, which states that “the purpose of the Bank is: To assist in the reconstruction and development of territories of members by facilitating the investment of capital for productive purposes, including the restoration of economies destroyed or disrupted by war”.24

The humanitarian approach

Humanitarian actors centre their work on the protection and assistance of victims of conflict, violence and other disasters. There is no standard definition for humanitarian actors or, more broadly, the humanitarian system.25 Broadly speaking, this note relates humanitarian action with emergency situations, in line with the common understanding of humanitarian action. More specifically, the term “humanitarian actor” is used here to refer to relevant UN agencies and the components of the Movement. Although this somewhat narrow focus is challenged by the proliferation of other “non-traditional” humanitarian actors such as the private sector, bilateral donors and the military,26 it is used here because all examples provided, and the ensuing discussion, involve activities carried out by UN agencies and the Movement. The work and characteristics of other essential components of the humanitarian system, such as emergency relief non-governmental organizations (NGOs), are not described here.

The work of the UN humanitarian agencies and the Movement is governed by a common set of principles that make it different from the work of other actors in the humanitarian space who provide emergency relief not necessarily based on principles and often underpinned by political, military and economic objectives.27 These principles are humanity (addressing human suffering wherever it is found), neutrality (not taking sides in conflict or favouring a particular ideological, racial, political or religious group), impartiality (providing aid on the basis of need alone, giving priority to the most urgent cases and making no distinction on the basis of nationality, race, gender, religious belief, class or political opinions) and independence (being autonomous from any political, economic or military objectives).28 In upholding these principles, humanitarian organizations build long-term partnerships with a range of stakeholders, to support both their emergency relief work and their conflict prevention activities.

Within the UN system, three entities have primary roles in delivering humanitarian assistance, including water services, during protracted armed conflict: the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, the UN Children's Fund (UNICEF) and the World Food Programme, with the Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs being responsible for coordinating responses.29 At the regional level, the UN Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) provides assistance and protection for some 5 million registered Palestinian refugees, including those affected by armed conflict.30

In specific regard to the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), neutral, independent and impartial humanitarian action in situations of armed conflicts and other situations of violence31 is at the heart of the organization's mandate and is a fundamental part of its identity and its ability to operate in conflict zones. Alongside these principles, the ICRC also operates under the principles of voluntary service, unity and universality.32

The ICRC seeks dialogue with all actors involved in a given situation of armed conflict or violence as well as with the people suffering the consequences in order to gain their acceptance and respect. This approach generally provides the ICRC with the widest possible access both to the victims of violence and to the actors involved. It also helps to ensure the safety of the organization's staff. In this way, the ICRC is able to reach people on all sides of the front lines in active conflict areas around the world.

Barriers to bridging the humanitarian and development divide

Despite the broad recognition that protracted conflicts are challenging development and poverty reduction efforts and that humanitarian and development interventions need to be better linked, challenges to effective coordination and collaboration between humanitarian and development actors remain. Some of the challenges depend on the protracted armed conflict in question, the country contexts, and the specific organizations involved. However, some general challenges common to most if not all protracted conflicts can be identified. Based on experience and the existing literature,33 this section groups the challenges into barriers that make working across the humanitarian and development divide difficult.

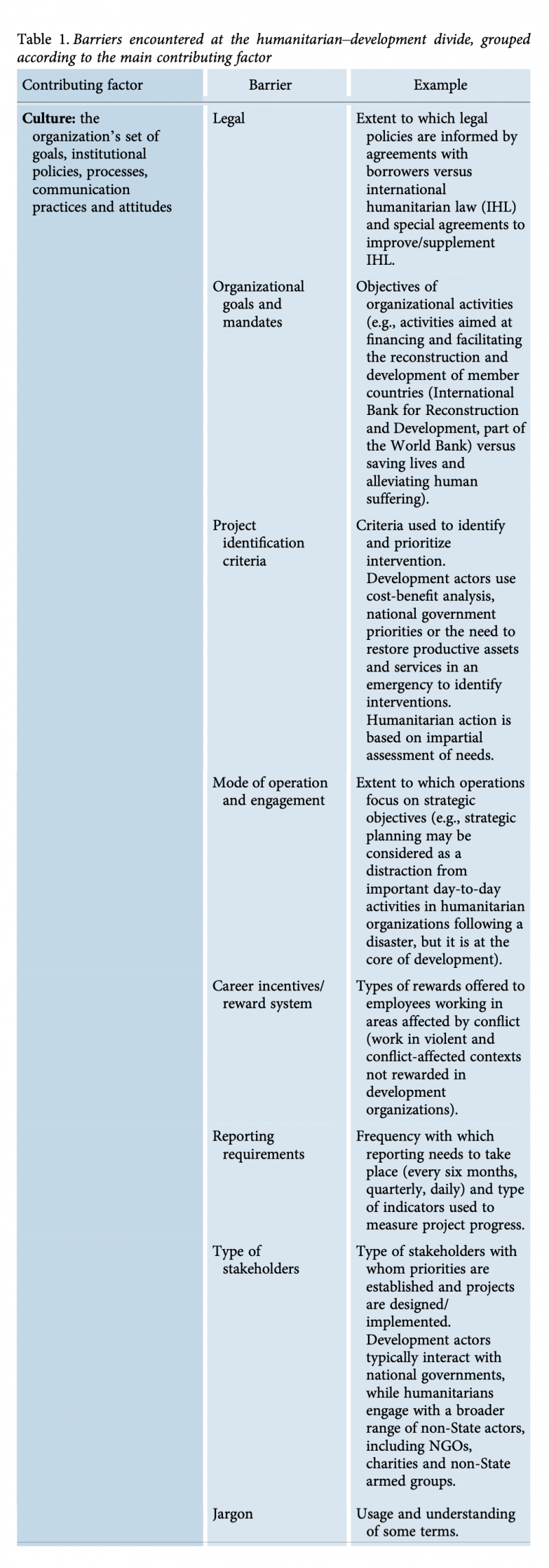

Barriers can arise for a range of reasons, including the different goals and mandates of the organizations involved, the type of financing mechanisms relied upon and the expertise available. The barriers identified here relate to the organizational environment (reflecting institutional culture and incentives, capacity and financing practices) within which development and humanitarian workers carry out their functions before, during and after a protracted conflict. The key message from this section is that an improved understanding and identification of these barriers can help development and humanitarian actors achieve better integration of their respective efforts and ultimately help them to accomplish their respective objectives without undermining each other's work.

To help individuals engaged in humanitarian and development work describe and analyze the barriers affecting their actions, the barriers are grouped according to three major contributing factors: culture, cash and capacity.

“Culture” refers to an organization's set of goals, processes, communication practices and attitudes, among other factors. It also encompasses the institutional architecture, including institutional frameworks and policies. Different organizations have different institutional policies – including legal agreements – that guide a project's preparation, appraisal, negotiation and approval. This is reflected in the type of institutional requirements that have to be met for a project to be approved in a development organization as compared to a humanitarian organization. Many of the economic, technical, environmental, social and fiduciary aspects used to appraise projects within a development organization may not be relevant for a humanitarian intervention, in turn creating a culture barrier.

Culture includes barriers such as lack of career incentives, which can prevent successful interactions between humanitarian and development actors by discouraging workers from designing and implementing projects outside of their respective organizations’ comfort zones. In practice, lack of career incentives also means that staff from development organizations are not rewarded (i.e., in terms of career advancement) for their work in fragile and conflict-affected countries.

Barriers related to culture might arise from the different types of stakeholders with whom development and humanitarian actors engage. Development actors tend to work with national governments and private sector stakeholders, whilst some humanitarian agencies often work through NGOs and directly with the affected population.34 This focus on national-level decision-making means that development actors are often unable to assist those outside of the reach of national authorities, who are often the most vulnerable and in need. In contrast, the principle of neutrality underpinning humanitarian action means that humanitarian assistance can be directed to groups and communities which development actors may not consider as counterparts or implementing partners because of political reasons or existing international sanctions, allowing these organizations to have a much wider reach.

The different purpose, and related language and practices, driving humanitarian and development workers constitutes the most significant barrier related to culture. Humanitarian work focuses on saving lives – that is, directly addressing the immediate and primary needs of individuals affected by conflict and violence – while development work traditionally seeks to develop and implement more systemic and transformational economic and social agendas, aimed at strengthening institutions and favouring equitable economic growth, among other factors. These different lenses through which humanitarian and development actors “live the missions” of their respective organizations and view the reality on the ground can act as a significant culture barrier, creating communication problems and misunderstandings.

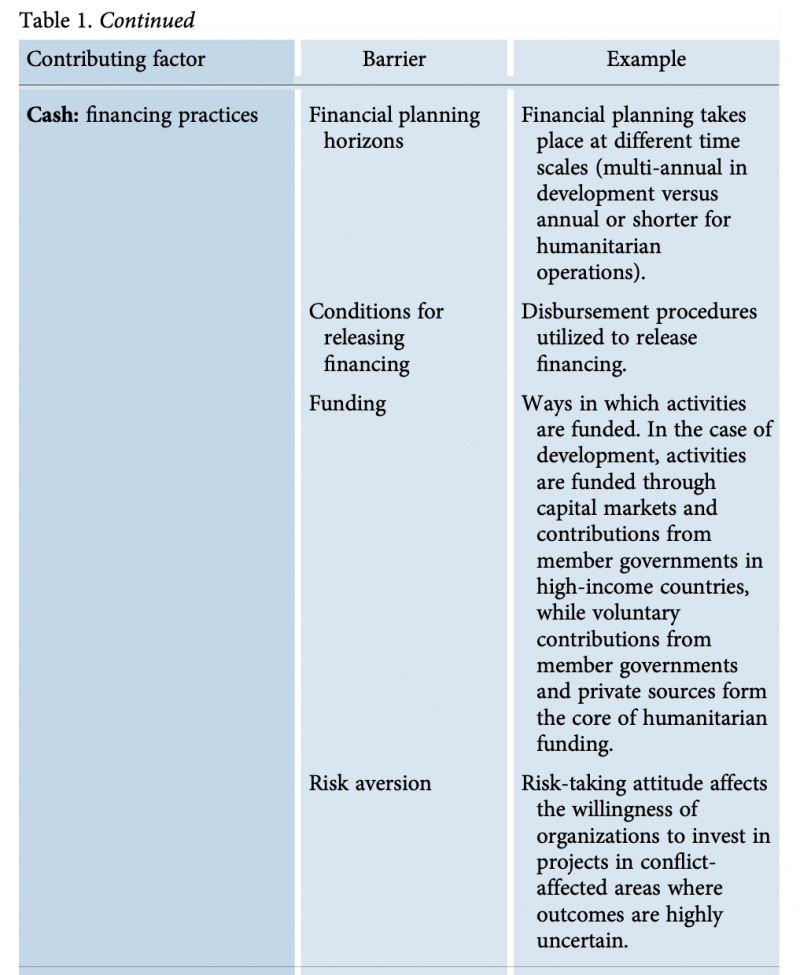

“Cash” refers to all aspects related to financing practices employed by humanitarian and development actors. It includes barriers arising from the nature of the financial instruments used and the “business” models applied. For instance, the short-term financing traditionally provided to humanitarian actors can make multi-year planning difficult, therefore reducing the incentives to connect with development actors and their longer-term plans. It also covers barriers arising from financing conditions, which may mean in practice that development agencies release financing too late in a crisis to promote synergies with humanitarian work. Cash barriers are also engendered by risk attitudes, with development agencies typically trying to avoid the added uncertainty layer created by implementing projects in areas at risk of conflict or with active conflict. Although World Bank documents suggest that addressing violent conflict is becoming a strategic priority in many countries,35 the risk-taking needed to carry out such engagements is still lacking.36

“Capacity” includes all barriers arising from human resources and expertise. Staff within humanitarian and development organizations may face a range of barriers related to a lack of knowledge of the mandates, approaches and practices of other organizations. The protracted nature of armed conflicts raises issues that are not within the traditional comfort zone and know-how of many humanitarian organizations, such as supporting the institutional capacity of utilities, water resources management and allocation, and urban planning. Similarly, staff from development organizations are oftentimes not familiar with humanitarian practices and mandates or with designing projects in contexts affected by conflict and violence, where, for instance, there are real risks of these same projects reinforcing inter-group tensions and fuelling divisive narratives.37 This lack of capacity often makes communication between development and humanitarian actors challenging, compounding the culture barrier. In other instances, barriers related to capacity may be a result of a lack of willingness or possibilities for staff to learn from other departments or of the difficulty encountered when transferring operational experience gained from long-term engagements from one organization to another.

These three “C”s provide a structure for grouping and communicating some of the barriers encountered when working across the humanitarian–development divide, not a normative guidance on what to do to remove them, as this will depend on the context and project in question. Under each factor, a series of commonly encountered barriers is listed in Table 1.

Table 1, contributing factor: Culture

Table 1, contributing factor: Cash

Table 1, contributing factor: Capacity

Overcoming the barriers helps to generate synergies, joint planning – while not undermining humanitarian principles and the funding modalities of development actors/banks – and eventually implementation as one work stream. On the other hand, not overcoming the barriers means disjointed operations in the field and, in some cases, humanitarian action undermining development responses and vice versa.

Overcoming the barriers: Working at the humanitarian–development interface in the water sector

To understand how the barriers described in the previous section can be overcome, this section provides a personal perspective building on World Bank water sector projects in the Middle East (Yemen, Jordan, Lebanon) and in several countries in Sub-Saharan Africa.38 By describing these experiences, the note will give some insight on the type of approaches that development actors can employ to overcome the barriers. The three phases of a protracted armed conflict are examined, as the nature of engagement of development actors and their complementarities with humanitarian work might change over time as the crisis evolves. The first phase (before the crisis) covers all interactions between development and humanitarian agencies targeted at preventing armed conflict in fragile contexts, and is discussed because it offers significant opportunities for overcoming the humanitarian–development barriers and paving the way for coordinated efforts should conflicts arise. In a situation of shock or when conflict escalates (second phase), development agencies need to remain engaged as much as possible. In situations of recovery and development opportunity (third phase), agencies need to balance the short-term efforts placed on providing urgently needed water supply and sanitation services with the longer-term effort placed on re-establishing sector oversight roles and the capacity of local institutions. The rationale for discussing humanitarian–development interactions separately for each of these three phases stems from the recognition that operating contexts and priorities change during the different phases of a protracted armed conflict, requiring different types of responses to be implemented and different barriers to be overcome.

Before the crisis

Before the crisis, development agencies need to work to prevent armed conflict in contexts that are already fragile in order to prevent countries from slipping into instability and to protect development gains (i.e., as a risk mitigation measure for existing interventions). Preventing conflict requires a range of measures, from addressing inequalities and exclusions in access to power and services, to making institutions more legitimate and inclusive. The UN and the World Bank have identified sustainable and inclusive development as key to preventing violent conflict.39 In the water sector, this translates into dialogue, policies and investments targeted at promoting sustainable and inclusive water management and service delivery. Although the primary responsibility falls on governments, development agencies play a role in supporting the creation of systems and practices aimed at avoiding issues such as groundwater over-exploitation, pollution of surface water bodies or politically biased water service delivery. Creating incentives for sustainable management and delivery means acting before the resources are depleted or water-related disasters strike, in order to prevent such disasters from becoming risk multipliers in fragile contexts.40

Development agencies are increasingly realizing the importance of adapting their culture and practices to operate in areas at high risk of armed conflict and to contribute to peacebuilding. First, development agencies are increasingly applying conflict-sensitive approaches to their interventions,41 evaluating the impact of investments also on the basis of their potential to reduce or increase the risk of conflict. At the World Bank, this has meant requiring project teams to identify any potential linkages between their proposed projects and drivers of fragility or resilience identified by the institution's country fragility analyses.42 This helps in overcoming the culture and capacity barriers arising from project design and evaluation criteria that do not account for the potential interactions between development interventions and armed conflict.

Designing development interventions before the crisis means building teams that include expertise on fragility and conflict, to overcome capacity barriers. It also entails building capacity outside of the development agency, using convening power to bring together humanitarian actors with stakeholders typically labelled “development-oriented” such as the private sector, water utilities, river basin authorities and government agencies. This could go as far as offering formal training to humanitarian workers on issues such as cost recovery in urban utilities, regulation of private water vendors, and the experiences of successful transitions from humanitarian to country-led water service delivery programmes.

Beyond addressing barriers related to capacity, World Bank experience shows that integrating water-related interventions within broader, country-wide strategies as well as sector strategies implemented by other operators in fragile contexts can improve outcomes and linkages with other agencies, overcoming the culture barriers. Sharing information and formally setting up venues for exchange and discussion helps to overcome barriers related to different mandates and modes of operation. Development agencies are set to benefit from a more systematic interaction and consultation with humanitarian actors in developing their long-term (typically five-year) country engagement plans (called “country partnership frameworks” at the World Bank). A framework for discussion with humanitarian actors helps to ensure that their expertise in specific dynamics, vulnerabilities and needs deriving from potential conflict (e.g., predictions of new influxes of displaced persons) is considered in development plans.

In the case of Palestine, this translated into the Water Sector Working Group, a forum for information-sharing between the Palestinian Water Authority, donors, and international and local implementing agencies, including humanitarian actors.43 This type of information-sharing approach can yield better support for governments as well as building relationships and communication between humanitarian and development actors. In particular, producing and sharing asset inventories of stocks (i.e., spare parts in the warehouse), equipment, and the laydown of critical water infrastructure should become a key element of water sector dialogue in contexts at risk of conflict.

Information-sharing frameworks between humanitarian and development actors before a crisis can also extend to setting up communication protocols to be activated in the event of a crisis. An example of this measure to overcome culture barriers comes from the World Bank–UN operational annex communication protocol.44 According to this protocol, immediate contacts must be made between the most senior World Bank and UN officials at the country level at the outset of a crisis, followed by close and continued communication among institutional teams responsible for projects in headquarters to ensure that all relevant information is shared.45

During the crisis

In a situation of active armed conflict or when conflict escalates, development agencies tend to decrease their engagement or withdraw altogether, while humanitarian agencies step up their engagement to promote respect for international humanitarian law and provide basic services. Given that international development is based on engagement with States and national governments, development agencies are highly constrained from engaging in situations of armed conflict because of the emergence of non-State actors who are uninterested in poverty reduction and are oftentimes in conflict with national governments. This constraint is particularly true nowadays because most conflicts involve more than one armed group, thus making it more difficult for development agencies to engage.

Development agencies often refrain from engaging with non-State actors, including non-State armed groups, because this may be perceived by national governments as legitimizing them, and may pose additional challenges if these same actors are also internationally sanctioned. In addition, given the inherent political nature of development planning, development agencies may not be perceived as impartial by non-State actors, or, if they do engage with non-State actors, they incur the risk of legitimizing them in the eyes of national governments, thus compromising important relationships and further constraining their ability to operate in a situation of crisis and recovery.

Development agencies are increasingly realizing, however, that withdrawing altogether can be damaging for future post-conflict development efforts. While the World Bank's articles prevent it from providing humanitarian assistance, this culture barrier has been partly overcome by operational policy OP8.00,46 which allows for rapid response to emergencies, including to restore essential water supply and sanitation services, and policy OP10.00, which allows for accelerated project preparation or restructuring in situations of urgent need.47

National governments, which are the typical counterparts of development agencies, may not be able to implement the needed emergency activities during a crisis, and the development agency may partner with different organizations, such as the UN or the ICRC, to develop and implement programmes in collaboration. This increased collaboration between the World Bank and humanitarian agencies is a recent positive trend, and is part of broader World Bank efforts to develop strategic partnerships with key humanitarian actors such as the ICRC.48 In the long term, these strategic partnerships should allow for more systematic handovers of essential services and some projects between development and humanitarian actors when a conflict sets in. They should also allow for an improved understanding of mandates, which will help to remove some of the culture barriers and ensure that key organizational aspects such as neutral, independent and impartial humanitarian action for humanitarian organizations are respected.

The active conflict in Yemen provides a first example of how barriers can be overcome during a crisis. The protracted armed conflict is posing serious risks to human development in Yemen. Just in relation to water access, about 20 million Yemenis are estimated to lack access to clean drinking water and sanitation services.49 To mitigate these long-term impacts of conflict, the World Bank has approved an emergency crisis response project of which a significant part deals with maintaining water service provision and expanding community infrastructure associated with clean water supplies. Staying engaged in Yemen has meant first of all overcoming barriers related to financing constraints, to allow for the implementation of an emergency water, health and nutrition project, budgeted at $683 million, through the World Health Organization and UNICEF.50

To overcome the cash and culture barriers, the project applies the Fiduciary Principles Accord developed by the World Bank in partnership with the UN.51 Rather than seeking project-based convergence on policies and procedures, the Accord recognizes the differences between the World Bank and UN organizations and focuses on defining a shared set of principles52 (on financial management, procurement, project design, implementation and monitoring, treatment of fraud and corruption) that are consistent with the particular institutional policies of the other organization. In practice, this means that World Bank and UN organizations don't have to carry out ex ante assessments or due diligence of the other organization's practices and requirements before starting to execute activities. This approach overcomes the culture and cash barriers by relying on each organization's “self-certification” that its internal practices are consistent with the agreed standards of the Fiduciary Principles Accord. Similar approaches could be tested and implemented with other humanitarian and development agencies.

The World Bank's efforts to remain engaged in Yemen's protracted conflict are the result of a clear change in approach and organizational culture that advocates for the institution to be an active promoter of peace and social stability. This stems from the recognition that maintaining basic services, as well as national implementation capacity and structures, helps to preserve the foundations for post-conflict recovery of the water supply and sanitation sector, as well as other sectors. Yet this is a one-of-a-kind activity, illustrating how much still needs to be learned from engagement during active conflicts, as also demonstrated by the request of the World Bank's board for sharing and building upon the knowledge generated from this type of engagement.53 Other organizations with different mandates and modes of operations (e.g., Mercy Corps) have also managed to change and adapt their operations in response to the evolution of conflicts.54 For example, the ICRC has adapted its operations to provide immediate assistance and is increasingly taking on long-term projects to aid civilians in need, notably water and habitat services and provision of prosthetics.

As noted above, the consequences of protracted armed conflicts often spill over into neighbouring countries not directly involved in the conflict. A development approach to addressing the consequences of protracted armed conflict requires supporting the humanitarian efforts of governments whose ability to provide basic services and regulate resource use has been strained by spillover effects, such as a sudden influx of refugees. To support countries hosting a large number of refugees, the World Bank has promoted a Global Concessional Financing Facility, which provides concessional loans (i.e., loans that have a zero or very low interest rate and repayments that are stretched over twenty-five to forty years) to middle-income countries affected by refugee crises across the world. To be eligible for this concessional funding, countries need to (1) host at least 25,000 refugees, or refugees must amount to at least 0.1% of the population; (2) have an adequate framework for the protection of refugees; and (3) have an action plan or strategy with concrete steps, including possible policy reforms for long-term solutions that benefit refugees and host communities.55 Developing this facility required the development of an innovative financing model, overcoming the cash barriers related to the ineligibility of some countries for concessional loans. Allocations from the Global Concessional Financing Facility are now being used in Jordan and Lebanon to support projects to improve infrastructure and public service delivery, including water supply and sanitation.56

The approach advocated here – and increasingly being adopted by the World Bank57 – means that reconstruction and development need to start before conflict is over. This might include, for instance, working with sub-national or local governments, NGOs and charities rather than more traditional World Bank partners such as national governments and UN agencies. In some contexts, there may not be a functioning national government; however, there might be local governments and institutions that can lay out the foundations of a recovery and reconstruction programme.

Engaging in a situation of crisis also means taking on a more non-conventional advocacy role. Development agencies should use their expertise and convening power to identify critical infrastructure (i.e., infrastructure essential for the health and well-being of people), including water infrastructure, and raise awareness about its importance for development, livelihoods and well-being. This is particularly important given the growing evidence of the impact of war on water infrastructure, resulting from incidental damage and intentional targeting of critical infrastructure during war.58

Situations of recovery and development opportunity

When conflict subsides, humanitarian and development agencies need to work together to address remaining emergency needs (e.g., those of displaced people) while rehabilitating infrastructure and creating the conditions for sustainable resource use and service delivery. This requires balancing the relative effort placed on providing urgently needed emergency relief and water supply and sanitation services with the effort placed on re-establishing sector oversight roles and the capacity of local institutions to oversee and manage service delivery in the long term.59

A first experience in bridging emergency relief with longer-term solutions comes from Somalia. The country is not eligible for International Development Association (IDA) financing from the World Bank due to outstanding arrears.60 To overcome this cash barrier, the World Bank has leveraged a first-of-its-kind partnership arrangement with the ICRC and the UN Food and Agricultural Organization in order to implement a $50 million emergency drought response and recovery project to rapidly deliver food, water, cash and basic goods to half a million people and provide vaccinations or treatment to the livestock of 200,000 people.61

The project aims to bridge the humanitarian–development divide by focusing on short-term solutions for immediate response and delivery of services aimed at confronting the consequences of drought, as well as long-term solutions focused on livelihood-centred activities. To meet the immediate needs of up to 656,000 people in Somalia, the World Bank is financing activities not typically included in its projects such as water trucking, unconditional cash grants to assist households with purchase of water, household water treatment, deepening of hand-dug wells, and provision of extra storage.62 This set of short-term measures is accompanied by investments to support medium-term recovery, including rehabilitation of existing irrigation canals, restoration of catchments and erosion control.

At the core of this experience, there is a recognition of the dire humanitarian crisis in Somalia as well as a formal request for support from the Federal Government of Somalia. There is also, as noted for the case of Yemen, an increasing strategic interest in the part of the World Bank to engage early on in fragile contexts in order to reduce the risk of further fragility and provide support that overcomes cash barriers to successful humanitarian–development engagement.

Another set of experiences bridging emergency relief with development efforts in situations of recovery comes from the World Bank's Water and Sanitation Program (WSP) engagement in Sub-Saharan Africa. Through its experience in fragile and conflict-affected countries in Sub-Saharan Africa, the WSP identified primary data collection as a key instrument for successfully working at the humanitarian and development interface in situations of development opportunity. Data on water service delivery – water point mapping, water quality monitoring, and service-level benchmarking – helps development agencies and donors to see which delivery models work well, contributing to a shift from humanitarian response and temporary coping arrangements to country-led government programmes.63

Experiences from the WSP also suggest that timing is a critical issue for working at the humanitarian–development interface in situations of recovery. Development agencies should try as much as possible to remain engaged during a crisis, and should then engage as soon as they are able in the recovery period. Evidence from countries in Sub-Saharan Africa affected by armed conflict shows that as time passes, it becomes progressively harder to build government capacity to oversee the water sector and to reform utilities.64 This is because, as time passes, governments and water utilities lose capacity and the number of non-State and informal private suppliers increases, making it harder to re-establish sector delivery and oversight capacity in the long term. Early engagement in the recovery period helps development agencies to interface directly with humanitarian actors, to build upon their understanding and actions and to allow for more systematic transfer of projects, services and contacts from humanitarian actors to national authorities, supported by development agencies.

Finally, in situations of recovery, development agencies need to enhance the internal capacities of government agencies and water utilities, particularly on aspects related to financial sustainability and regulation. Strengthening capacity with respect to financial sustainability helps promote cost recovery in water supply and sanitation services delivery.65 Regulatory capacity-building provides governments with the ability to oversee and work more closely with the private sector and other independent service providers, which often account for a large share of water service delivery during and after a protracted conflict.

Conclusion

This note has discussed the challenge of water service delivery during the different phases of a protracted armed conflict, describing the barriers that might impede successful transition from humanitarian to development interventions and suggesting some possible ways of overcoming them. The note presented examples of World Bank engagements and projects in order to illustrate how coordination and transition from humanitarian to development interventions across phases of protracted conflict can be improved. This includes setting up a Water Sector Working Group in Palestine to overcome culture and capacity barriers and facilitate information-sharing, and applying the Fiduciary Principles Accord developed by the World Bank in partnership with the UN to overcome cash barriers and provide emergency crisis response in Yemen.

Most barriers between humanitarian and development efforts still persist. Some of the approaches required to bridge humanitarian and development action, most notably incentives within organizations and institutional policies, are still far from influencing mainstream development practice. This finding is in line with broader assessments of development action in fragile contexts, which have found that many of the constraints internal to the operations of development actors still prevent them from successfully engaging.66

From the perspective of a development agency, several institutional policies and incentives need to be modified in order to mainstream engagement before, during and after protracted conflict. First, addressing human resource constraints is essential to bridging the humanitarian–development divide. In practice, this means increasing the number of staff in the field and improving incentives and means for career progression for development agency staff working in countries affected by protracted conflict. Second, operational approaches need to be revised and updated to more effectively consider and address the financial and technical difficulties associated with implementing projects during protracted conflict. Third, capturing, developing and disseminating knowledge on what works and what does not work in terms of engagement during protracted conflict is essential. This includes providing support and advice to internal as well as external actors (i.e., representatives from humanitarian agencies and governments) through specialized courses and guidance notes.

- 1United Nations (UN), The Millennium Development Goals Report 205, New York, 205, p. 8, available at: www.un.org/millenniumgoals/205_MDG_Report/pdf/MDG%20205%20rev%20%28July… (all internet references were accessed in May 2020).

- 2World Bank, Forcibly Displaced: Toward a Development Approach Supporting Refugees, the Internally Displaced, and Their Hosts, Washington, DC, 017.

- 3Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), States of Fragility 2015: Meeting Post-2015 Ambitions, Paris, 2015.

- 4UN, above note 1, p. .

- 5John Norris, Casey Dunning and Annie Malknecht, Fragile Progress. The Record of the Millennium Development Goals in States Affected by Conflict, Fragility and Crisis, Center for American Progress and Save the Children, 201.

- 6Paul Collier, V. L. Elliott, Håvard Hegre, Anke Hoeffler, Marta Reynal-Querol and Nicholas Sambanis, “Breaking the Conflict Trap: Civil War and Development Policy”, World Bank and Oxford University Press, Washington, DC, 2003, pp. 13 ff.

- 7For a discussion of the ambition and challenges of SDG 6 on clean water and sanitation for all, see Veronica Herrera, “Reconciling Global Aspirations and Local Realities: Challenges Facing the Sustainable Development Goals for Water and Sanitation”, World Development, Vol. 118, June 2019.

- 8International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), Protracted Conflict and Humanitarian Action: Some Recent ICRC Experiences, Geneva, 2016, p. 9.

- 9For a discussion of the importance of considering the cumulative impacts of conflict, see ICRC, Urban Services during Protracted Armed Conflict: A Call for a Better Approach to Assisting Affected People, Geneva, 2015.

- 10World Bank and UN, Pathways for Peace: Inclusive Approaches to Preventing Violent Conflict, Washington, DC, 2018. p. 255.

- 11World Bank, The Toll of War: The Economic and Social Consequences of the Conflict in Syria, Washington, DC, 2017.

- 12Shantayanan Devarajan and Lili Mottaghi, “The Economic Effects of War and Peace”, Middle East and North Africa Quarterly Economic Brief, World Bank, Washington, DC, January 2016.

- 13Ibid.

- 14Shantayanan Devarajan, “An Exposition of the New Strategy: Promoting Peace and Stability in the Middle East and North Africa”, World Bank, Washington, DC, 2015.

- 15OECD, The Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness and the Accra Agenda for Action, 2008, p. 4, available at: www.oecd.org/dac/effectiveness/34428351.pdf.

- 16“A New Deal for Engagement in Fragile States”, International Dialogue on Peacebuilding and Statebuilding, p. 2, available at: https://tinyurl.com/yc9zgbl9.

- 17More details on SDG 16 can be found on the Sustainable Development Knowledge Platform, available at: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/sdg16.

- 18For an elaboration of this point, see Filipa Schmitz Guinote, A Humanitarian–Development Nexus that Works”, Humanitarian Law and Policy Blog, 21 June 20, available at: http://blogs.icrc.org/law-and-policy/20/06/21/humanitarian-development-….

- 19Perspectives on development are varied and multifaceted. For a more detailed account of development from the perspective of the World Bank, see Mary Morrison and Shani Harris, Working with the World Bank Group in Fragile and Conflict-Affected States: A Resource Note for United Nations Staff, World Bank, Washington, DC, 2015.

- 20For a more detailed account of the significance of institutions in economic development, see Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson, “The Role of Institutions in Growth and Development”, in David W. Brady and Michael Spence (eds), Leadership and Growth, World Bank, Washington, DC, 10.

- 21On the role of climate change, see, for instance, Asian Development Bank, A Region at Risk: The Human Dimensions of Climate Change in Asia and the Pacific, Manila, 2017. On the importance of justice and political stability, see UN Briefing on SDG 16, available at: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/files/metadata-compilation/Metadata-Goal-16….

- 22Fiduciary control ensures that development funds are transparently used for the intended purposes, that they achieve value for money, and that they are accounted for. In fragile contexts, countries are often not able to guarantee this fiduciary control, which increases the risk of corruption and inappropriate use of development funds.

- 23World Bank and UN, above note 10, p. 249.

- 24United Nations Monetary and Financial Conference, Articles of Agreement: International Monetary Fund and International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, US Treasury, Washington, DC, 1944, available at: https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/files/docs/historical/martin/17_07_194407….

- 25John Borton, Future of the Humanitarian System: Impacts of Internal Change, Feinstein International Center, Somerville, MA, 2009

- 26Justin Armstrong, The Future of Humanitarian Security in Fragile Contexts, European Interagency Security Forum, 2013.

- 27Claudia McGoldrick, “The State of Conflicts Today: Can Humanitarian Action Adapt?”, International Review of the Red Cross, Vol. 97, No. 900, 2015.

- 28UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, “OCHA on Message: Humanitarian Principles”, 2012, available at: www.unocha.org/sites/dms/Documents/OOM-humanitarianprinciples_eng_June1…; World Food Programme, “Humanitarian Principles”, WFP/EB.A/2004/5-C, Rome, 2004; UNICEF, “UNICEF's Humanitarian Principles”, 2003, available at: https://tinyurl.com/y7cgmasy; Office of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, “Humanitarian Principles”, available at: https://emergency.unhcr.org/entry/1147/humanitarian-principles.

- 29See the UN's “Deliver Humanitarian Aid” web page, available at: www.un.org/en/sections/what-we-do/deliver-humanitarian-aid/.

- 30For more details on UNRWA's work, visit the UNRWA website at: www.unrwa.org/who-we-are.

- 31“Other situations of violence” are situations in which acts of violence are perpetrated collectively but which are below the threshold of armed conflict according to the ICRC. See ICRC, “The International Committee of the Red Cross's Role in Situations of Violence Below the Threshold of Armed Conflict”, International Review of the Red Cross, Vol. 96, No. 893, 2014.

- 32ICRC, “Fundamental Principles: Yesterday, Today, Tomorrow”, 7 October 2015, available at: www.icrc.org/en/document/red-cross-principled-humanitarian-action.

- 33See, for instance, Christina Bennett, The Development Agency of the Future: Fit for Protracted Crises?, Overseas Development Institute Working Paper, London, 2015; Lucy Earle, “Addressing Urban Crises: Bridging the Humanitarian–Development Divide”, International Review of the Red Cross, Vol. 98, No. 901, 2016; Kristalina Georgieva and Jakob Kellenberger, “Discussion: What are the Future Challenges for Humanitarian Action?”, International Review of the Red Cross, Vol. 93, No. 884, 2011.

- 34World Bank and UN, above note 10, p. 249.

- 35World Bank, World Development Report 2011: Conflict, Security, and Development, Washington, DC, 2011.

- 36World Bank, World Bank Group Engagement in Situations of Fragility, Conflict, and Violence, Washington, DC, 2016, available at: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/24915.

- 37World Bank and UN, above note 10, p. 250.

- 38The countries that the World Bank Water and Sanitation Program worked in were the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Liberia, Nigeria, the Republic of Congo, Sierra Leone, Somalia, South Sudan and Zimbabwe.

- 39World Bank and UN, above note 10, p. xviii.

- 40Claudia W. Sadoff, Edoardo Borgomeo and Dominick de Waal, Turbulent Waters: Pursuing Water Security in Fragile Contexts, World Bank, Washington, DC, 2017.

- 41Several development agencies have produced guidelines for understanding and applying conflict sensitivity approaches in their interventions, including the “do no harm” approach. See, for example, Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency, “Conflict Sensitivity in Programme Management”, Stockholm, 2017; Conflict Sensitivity Consortium, “How-to Guide to Conflict Sensitivity”, UK Department for International Development, London, 2012.

- 42World Bank, “Results Framework and M&E Guidance Note”, Washington, DC, 2013.

- 43Sandra Ruckstuhl, Conflict Sensitive Water Supply: Lessons from Operations, Social Development Working Paper No. 127, Washington, DC, 2012.

- 44M. Morrison and S. Harris, above note 19, p. 24.

- 45Ibid.

- 46World Bank, Operational Manual: OP 8.00 – Rapid Response to Crises and Emergencies, Washington, DC, 2013.

- 47M. Morrison and S. Harris, above note 19, p. 24.

- 48See World Bank, “ICRC, World Bank Partner to Enhance Support in Fragile and Conflict-affected Settings”, 9 May 2018, available at: www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2018/05/09/icrc-world-bank-partner-to….

- 49World Bank, Yemen Integrated Urban Services Emergency Project, Washington, DC, 2017.

- 50World Bank, “Yemen Emergency Health and Nutrition Project”, Factsheet, Washington, DC, 2019, available at: www.worldbank.org/en/news/factsheet/2019/05/14/yemen-emergency-health-a….

- 51World Bank, World Bank and United Nations Fiduciary Principles Accord for Crisis and Emergency Situations, Washington, DC, 2008.

- 52Ibid., Annex C.

- 53World Bank, Yemen Emergency Crisis Response Additional Financing Project and Yemen Emergency Health and Nutrition Project: Chair Summary”, 2017, available at: https://tinyurl.com/ybaas4wy.

- 54See Mayada El-Zoghbi, “Bridging the Humanitarian and Development Divide”, CGAP Blog, 2017, available at: www.cgap.org/blog/bridging-humanitarian-and-development-divide.

- 55See World Bank, “Eight Countries Eligible for new IDA Financing to Support Refugees and Hosts”, 16 November 2017, available at: https://reliefweb.int/report/world/eight-countries-eligible-new-ida-fin….

- 56For a list of projects supported so far, see the Global Concessional Financing Facility website, available at: http://globalcff.org/supported-projects/.

- 57S. Devarajan, above note 14.

- 58ICRC, Bled Dry: How War in the Middle East is Bringing the Region's Water Supplies to Breaking Point, Geneva, 2015; Jeannie L. Sowers, Erika Weinthal and Neda Zawahri, “Targeting Environmental Infrastructures, International Law, and Civilians in the New Middle Eastern Wars”, Security Dialogue, Vol. 48, No. 5, 2017.

- 59Dominick de Waal , Water Supply: The Transition from Emergency to Development Support, World Bank, Nairobi, 2017.

- 60IDA is the World Bank's fund to provide concessional financing (loans extended on terms more generous than market loans, with interest rates below market rates and grace periods) through credits and grants to governments of the poorest countries. Eligibility for IDA support depends first and foremost on a country's relative poverty, defined as gross national income per capita below an established threshold and updated annually ($1,175 in fiscal year 2020). For some countries, like Somalia, there is no IDA financing because of protracted non-accrual status. For more information, see: http://ida.worldbank.org/.

- 61World Bank, Somalia Emergency Drought Response and Recovery Project, Washington, DC, 2017.

- 62Ibid.

- 63D. de Waal et al., above note 59, p. 13.

- 64Ibid., p. 36.

- 65Loan Diep, Tim Hayward, Anna Walnycki, Marwan Husseiki and Linus Karlsson, Water, Crises and Conflict in MENA: How Can Water Service Providers Improve Their Resilience?, IIED Working Paper, 2017.

- 66Erwin van Veen and Veronique Dudouet, Hitting the Target but Missing the Point? Assessing Donor Support for Inclusive and Legitimate Politics in Fragile Societies, International Network on Conflict and Fragility, OECD, Paris, 2017.