What's new in law and case law around the world? Protection of children in armed conflict: Thematic update on national implementation of international humanitarian law 2014–2019

The ICRC's Advisory Service on International Humanitarian Law aims to provide a systematic and proactive response to efforts to enhance the national implementation of international humanitarian law. Working worldwide, through a network of legal advisers, to supplement and support governments’ own resources, its four priorities are: (i) to encourage and support adherence to IHL-related treaties; (ii) to assist States by providing them with specialized legal advice and the technical expertise required to incorporate IHL into their domestic legal frameworks;1 (iii) to collect and facilitate the exchange of information on national implementation measures and case law;2 and (iv) to support the work of committees on IHL and other entities established to facilitate the IHL implementation process.

The update on national legislation and case law is an important tool for promoting the exchange of information on national measures for the implementation of international humanitarian law (IHL). This edition of the update will focus on concrete measures that States have taken in recent years on the thematic subject of this issue of the Review: strengthening the protection of children in armed conflict domestically and regionally. Children are especially vulnerable to armed conflicts and need special safeguards from the numerous dangers they face during armed hostilities and to help them rebuild their lives after the end of the conflict.

In its first part, the update will include relevant information related to accession and ratification of instruments providing for the protection of children in armed conflict, especially the Convention on the Rights of the Child and its Second Optional Protocol on the Involvement of Children in Armed Conflict. The second part of the update will include a compilation of domestic laws, case law and national and regional programmes and policies which have been introduced by States between 2014 and 2019 in order to strengthen the protection of children exposed or vulnerable to conflict-related abuse and mistreatment.

Update on the accession and ratification of IHL and other related international instruments

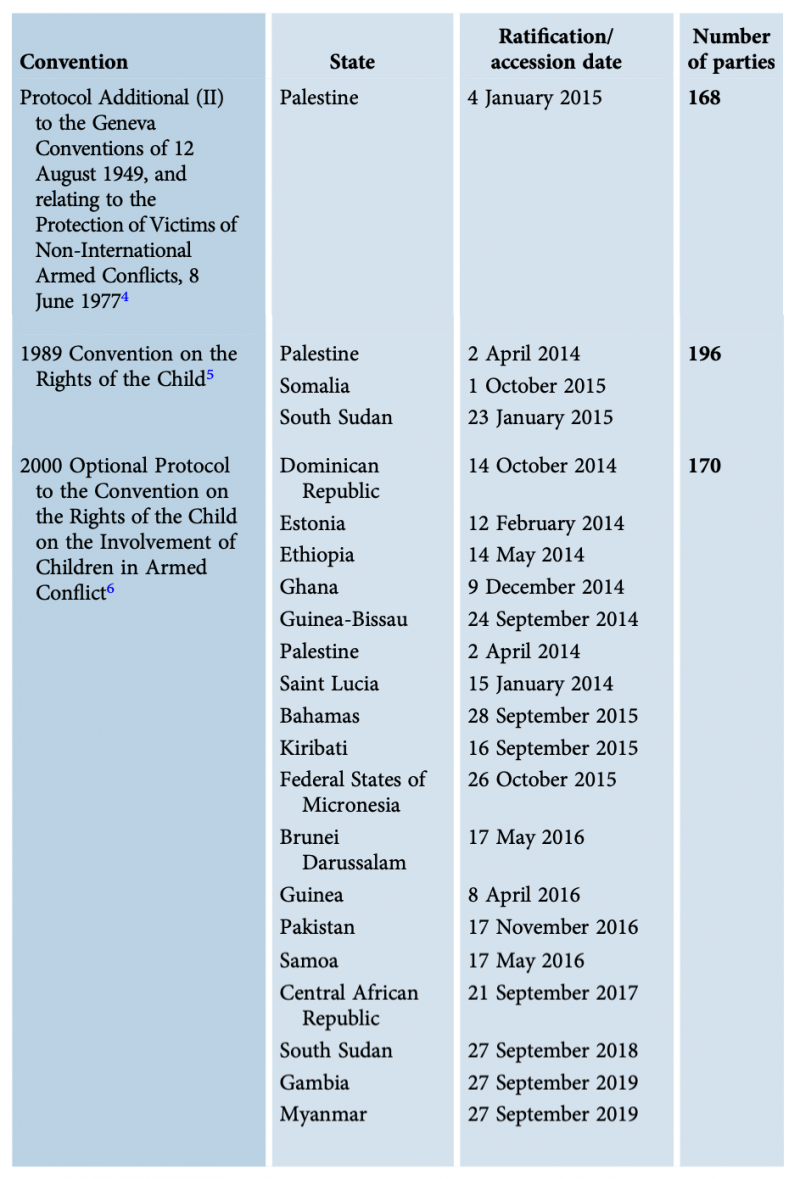

Universal participation in IHL and related treaties is a first vital step toward the respect of life and human dignity in situations of armed conflict. In the period under review, three international conventions and protocols related to the protection of children in armed conflict were ratified or acceded to by nineteen States.3 In addition to the 1977 Protocol Additional (II) to the Geneva Convention of 12 August 1949 relating to the Protection of Victims of Non-International Armed Conflicts, the other treaties are the 1989 Convention on the Rights of the Child and the 2000 Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the Involvement of Children in Armed Conflict. The period 2014–19 marks a notable adherence to the 2000 Optional Protocol, bringing the number of its States Parties to 170. This Protocol provides that its States Parties should take all feasible measure to ensure that individuals under the age of 18 are not mandatorily recruited into their armed forces or into armed groups distinct from the armed forces of a State, that such individuals are not used in hostilities, and that the minimum age for voluntary recruitment into States’ national forces be raised from 15 years. The widespread ratification of and accession to the 2000 Optional Protocol contributes to the strengthening of the protection of children below the age of 18 from direct exposure to the dangers of armed conflicts through their recruitment or participation in hostilities.

The following table outlines the total number of ratifications of and accessions to IHL treaties and other relevant international instruments related to the protection of children in armed conflict, from mid-January 2014.

Ratifications and accessions, 2014–19

From the above table: Protocol Additional (II) to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, and relating to the Protection of Victims of Non-International Armed Conflicts, 8 June 19774 ; 1989 Convention on the Rights of the Child5 ; 2000 Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the Involvement of Children in Armed Conflict6 .

National implementation of international humanitarian law

The laws and judicial decisions presented below were either adopted/promulgated/entered into force by States or delivered by domestic courts between 2014 and 2019. They demonstrate a commitment on the part of States to respect IHL and to protect children from the devastating effects of armed conflict. The majority of these laws include a particular focus on preventing and combating the recruitment of children into State forces and armed groups, or their use in hostilities. The countries covered are Afghanistan, Algeria, Austria, Bahrain, Bulgaria, Canada, Chad, Colombia, Estonia, France, Germany, India, Indonesia, Kyrgyzstan, Myanmar, Niger, Norway, Peru, the Philippines, Syria, Tajikistan, Tunisia, Turkmenistan, Ukraine, the United Arab Emirates and the Member States of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS).

This compilation is not meant to be exhaustive; it represents a selection of the most relevant developments collected by the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) relating to the implementation of rules of IHL pertaining to the protection of children in armed conflict. The full texts of these laws and case law can be found in the ICRC's Database on National Implementation of IHL.7

2014

Canada

Prohibiting Cluster Munitions Act, S.C. 2014, c. 278

On 6 November 2014, the government of Canada adopted the Prohibiting Cluster Munitions Act. The purpose of this Act is to implement Canada's commitments under the Convention on Cluster Munitions of 2008. The preamble of the Cluster Munitions Convention states that its States Parties are concerned that cluster munition remnants kill or maim civilians, including women and children, and while adopting this Convention, they are bearing in mind United Nations (UN) Security Council Resolution 1612 on Children in Armed Conflict.9

Chad

Presidential Ordinance No. 001/PR/2014 on Child Soldiers10

On 4 February 2014, the president of the Republic of Chad signed an Ordinance prohibiting and repressing the recruitment and use of children in armed conflicts.

Article 1 of the Ordinance prohibits the participation and involvement of children in armed conflict, as well as their enlistment of any nature in the State armed forces or armed groups. Article 2 of the Ordinance provides for imprisonment of five to ten years and fines for persons who have recruited or facilitated the enlistment or use of children in the State armed forces or in armed groups.

Estonia

Act Amending the Penal Code and Other Related Acts11

On 3 July 2014, the Act Amending the Penal Code was promulgated in Estonia. The amendment, which prohibits both the recruitment of children in armed forces and their engagement in acts of war, entered into force on 1 January 2015.

Under Article 102(3) of the Penal Code, acceptance or recruitment of a person younger than 18 years of age in national armed forces or armed units distinct from the national armed forces, or in engagement in acts of war, is punishable by one to five years’ imprisonment. The same act, if committed by a legal person, is also punishable by a fine.

In its report to the Committee on the Rights of the Child (G1618889), Estonia clarified the following: “[A]lthough under certain circumstances the active members of the Defence League may be considered as members of the armed forces, the restrictions applicable to junior members exclude such status. Engagement of minors, including junior members of the Defence League in direct acts of war will also remain prohibited.”12

Indonesia

Law No. 35 of 2014 on the Amendment of Law No. 23 of 2002 on Child Protection13

Law No. 35 was adopted on 17 October 2014, amending several provisions in Law No. 23 of 2002 on Child Protection. The main amendment is related to heavier criminal sanctions for sexual abuses against children.

Article 1.1 of the 2014 Law defines a child as anyone who is below 18 years of age. It also maintains the Article 15 provision under which children shall be protected from being involved in armed conflict or war. The exemplary memorandum to this particular provision stresses that such protection should be implemented both directly and indirectly in order to ensure the protection of children's physical and psychological welfare.

Further, Article 76H stipulates that recruiting or using children for military purposes is prohibited. This prohibition, as stated in Article 87, carries a maximum penalty of five years’ imprisonment or a fine of up to 100 million rupiah ($7,000).

2015

Algeria

Law No. 15-12 on Child Protection14

On 15 July 2015, the president of Algeria promulgated Law No. 15-12 on Child Protection.

The Law refers to the 2000 Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the Involvement of Children in Armed Conflict. It calls for global protection of children's rights, but also provides for the protection of children in the family, at school or in the street.

Under Article 2 of the Law, a child is anyone who has not attained the age of 18. Under the same provision, the Law defines the term “child in danger” as a child who is a refugee or a victim of sexual exploitation, armed conflicts or other cases of disturbance and insecurity, as that child is considered to be exposed to danger under the present Law.

Moreover, under Article 6 of the Law, the State guarantees the protection of the rights of the child from physical or sexual attacks, or attacks on his or her morale. Moreover, in situations of emergency, disaster and armed conflict, the State shall take all appropriate measures to establish the necessary conditions for the protection of the child's life and development, and to ensure his or her education in a sound and proper environment.

Bulgaria

Law on the Implementation of the Convention on Cluster Munitions and the Convention on the Prohibition of the Use, Stockpiling, Production and Transfer of Anti-Personnel Mines and on Their Destruction15

On 24 November 2015, the National Assembly of Bulgaria adopted the Law on the Implementation of the Convention on Cluster Munitions and the Convention on the Prohibition of the Use, Stockpiling, Production and Transfer of Anti-Personnel Mines and on Their Destruction (Anti-Personnel Mine Convention). The purpose of the Law is to implement Bulgaria's commitments under the two Conventions.

Article 30(1) of the Law defines victims as all individuals who have perished or suffered physical or psychological trauma, economic loss or difficulty in the enjoyment of their human rights as a result of the use of cluster munitions, anti-personnel mines and their remnants under the jurisdiction or control of the Republic of Bulgaria. Under Article 30(2), the spouses, children or parents of those individuals mentioned in Article 30(1) are also considered victims.

The preamble of the 2008 Convention on Cluster Munitions states that its States Parties are concerned that cluster munition remnants kill or maim civilians, including women and children, and that while adopting this Convention, they are bearing in mind UN Security Council Resolution 1612 on Children in Armed Conflict.16 The preamble of the 1997 Anti-Personnel Mine Convention states that its States Parties are determined to put an end to the suffering and casualties caused by anti-personnel mines and to the killing and maiming of innocent civilians, especially children.

India

Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act 201517

The Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act was adopted on 30 December 2015 and promulgated on 1 January 2016. The Act provides for a number of measures to be taken to ensure the proper care, protection, development, treatment, social reintegration, child-friendly adjudication, and rehabilitation of children alleged and found to be in conflict with the law, and children in need of care and protection.

Under Article 2(14)(xi) of the Act, a “child in need of care and protection” is defined as a child “who is victim of or affected by any armed conflict, civil unrest or natural calamity”.

Article 83(1) of the Act provides for criminal sanctions for the recruitment or use for any purpose of children by self-styled militant groups designated as such by the central government. This provision potentially expands the prohibition under Article 4 of the 2000 Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the Involvement of Children in Armed Conflict, which only prohibits and criminalizes the recruitment and use of children in hostilities.18

Tajikistan

Law of the Republic of Tajikistan No. 1196 on the Protection of the Rights of the Child19

Law No. 1196 on the Protection of the Rights of the Child was promulgated in Tajikistan on 18 March 2015.

Under Article 1 of Law No. 1196, a child is as an individual who has not attained the age of 18. The Law generally provides for the protection of the rights and freedoms of children, including their right to life, freedom, inviolability, honour, dignity, identity, health care, freedom of speech, property, dwelling, education, labour and rest. It also protects the rights of children in special educational institutions for minors, the rights of child refugees on the territory of Tajikistan, the rights of orphaned children and children without parental care, and the rights of disabled children, and it protects children from illegal movement across the State border.

Article 26 of Law No. 1196 prohibits the participation of children in hostilities and armed conflicts, as well as the creation of children's paramilitary groups, and the spreading of war propaganda and violence among children. The State is obliged to take all possible measures to ensure the protection of the rights of children in zones of hostilities and armed conflict and to take care of them. Children are to be provided with material, medical and other assistance, and, if necessary, should be placed in institutions for orphans and children left without parental care, or in institutions of the educational sector.

Tunisia

Organic Law No. 2015-26 of 7 August 2015 relating to the Fight against Terrorism and the Repression of Money Laundering20

On 7 August 2015, the president of Tunisia promulgated Organic Law No. 2015-26 relating to the Fight against Terrorism and the Repression of Money Laundering.

The Law places the State's efforts in these areas within the framework of respect for human rights and IHL. Article 2 of the Law provides for respect by the authorities responsible for its application of international, regional and bilateral conventions ratified by Tunisia in the field of human rights, the protection of refugees and IHL.

Under Article 10 of the Law, the perpetrator of a terrorist offence as provided for under the Law shall receive a maximum penalty if the offence was committed through the use of a child. This provision is without prejudice to the application of mitigating circumstances specific to children, who are subject to Tunisia's Code on the Protection of Children in accordance with Article 3 of the Law.

Turkmenistan

Law of Turkmenistan on the Introduction of Amendments and Modifications to the Criminal Code of Turkmenistan21

On 3 December 2015, the president of Turkmenistan promulgated the Law on the Introduction of Amendments and Modifications to the Criminal Code of Turkmenistan. The Law introduces into the Criminal Code eleven new articles under Chapter 21, which is titled “Crimes against Peace and Security of Mankind”.

The newly introduced Article 167(6) provides for criminal sanctions for crimes in violation of norms of IHL in times of armed conflict. In particular, para. 5 of this provision criminalizes the recruitment of individuals under the age of 15 in the armed forces and allowing their participation in hostilities. In addition, para. 6 of the same provision prohibits the recruitment of individuals under the age of 18 into armed groups that are distinct from the armed forces of the State, or the use of such individuals in hostilities as members of armed groups.

2016

Norway

Act on Military Service and Service in the Armed Forces (Defence Act)22

The Act on Military Service and Service in the Armed Forces was adopted on 12 August 2016 and came into force on 1 July 2017 in Norway.

Article 4 of the Act, titled “Restriction on Service for Those Under 18 Years of Age”, provides that persons who are under the age of 18 and serve in the Norwegian Armed Forces should not be trained to participate in combat-related activities, that they are not eligible for extraordinary service (defined in Article 17(3) of the Act), and that they will immediately be excused from service in situations where Norway is involved in an armed conflict, is threatened by one, or when the Armed Forces have commenced force generation.

The same amendment was also introduced into the former Military Service Act (LOV-1953-07-17-29, Article 4) and into the Military Service Regulations (FOR-2010-12-10-1605, Article 3(3) as modified by FOR-2014-12-19-1730).

Peru

Supreme Decree Approving the Protocol for the Care of Persons and Families Abducted by Terrorist Groups (Supreme Decree No. 010-2016-MIMP)23

On 29 July 2016, the Supreme Decree Approving the Protocol for the Care of Persons and Families Abducted by Terrorist Groups entered into force. Under Article 3 of the Protocol, its main objective is to promote the restitution of the rights and autonomy of people (including children, adolescents and families) rescued from the control of the remnants of the armed group party to the non-international armed conflict between 1980 and 2000.

Under Article 4 of the Protocol, the Prosecutor's Office specialized in terrorism crimes is competent to determine who is beneficiary of the programme. Beneficiaries are sorted into three groups: children and adolescents in alleged abandonment, adults alone, and adults with children and adolescents (families). Among others, people suspected of taking part in terrorist activities may not benefit from the programme.

Under Article 6, the Protocol will be implemented with an approach that takes into account the best interests of the child.

Under Articles 9.1 and 9.3 of the Protocol, during the rescue operation and during the emergency stage, police and armed forces shall protect the rights of children with disabilities. Children under three years of age and nursing infants shall remain with their mother or, if not, with their father. Unaccompanied children will be put under the care of other families within the rescued group.

Under Article 9.9, the Ministry of Education is tasked with providing children with preparation sessions for formal, intercultural and bilingual education, paying special attention to the educational needs of these children in coordination with personnel in charge of their mental health in order to avoid revictimization.

Tunisia

Organic Law No. 2016-61 of 3 August 2016 on the Prevention and Fight against Trafficking in Persons24

On 12 August 2016, the president of Tunisia promulgated Organic Law No. 2016-61 of 3 August 2016 on the Prevention and Fight against Trafficking in Persons. Under Article 1, the purpose of the Law is to prevent all forms of exploitation to which people, especially women and children, may be exposed, to combat trafficking, to punish the perpetrators, and to protect and assist victims. It also aims to promote national coordination and international cooperation in the fight against trafficking in persons within the framework of international, regional and bilateral conventions ratified by Tunisia.

Article 2(1) of the Law defines trafficking in persons in a broad manner, making its provisions applicable both in times of peace and in war. In addition, Article 2(2) of the Law defines “situation of vulnerability” with particular reference to, inter alia, children. In Article 2(5), the Law also addresses practices similar to slavery, which include the exploitation of children in criminal activities or in armed conflict, the adoption of children for exploitation of any form, and the economic or sexual exploitation of children in the course of their employment.

In Article 4, the Law provides for the application of Tunisia's Criminal Code, Code of Criminal Procedure, Code of Military Justice and other relevant texts to the offences of trafficking in persons and related offences provided for in the Law. Children are subject to the provisions of Tunisia's Code on the Protection of Children.

Under Article 5 of the Law, the consent of the victim will not be considered in the assessment of a potential offence committed through the means falling under the definition of trafficking in person under Article 2(1). In addition, where the victim is a child, the means of committing an offence under the Law is not restricted to the means listed in Article 2(1).

Chapter II (Articles 8–26) prescribes the punishment for the perpetrators of offences under the Law. Under Article 23, an aggravated punishment is imposed on the perpetrator when the victim is a child.

Ukraine

Law of Ukraine on Amendments to Some Legislative Acts of Ukraine on Strengthening Social Protection of Children and Supporting Families with Children25

On 26 January 2016, the president of Ukraine promulgated the Law on Amendments to Some Legislative Acts of Ukraine on Strengthening Social Protection of Children and Supporting Families with Children (Law on Amendments). The Law amends the Family Code of Ukraine, the Law on the Protection of Childhood and other laws by adding provisions on the protection of children in difficult circumstances, orphans or other categories of children that require special protection.

The amended Article 30 prohibits the participation of children in hostilities and armed conflict, including their recruitment, financing, material support, and training for the purpose of being used in armed conflicts of other States or violent acts aimed at overthrowing State power or violating territorial integrity. The provision also prohibits the use of children in hostilities or armed conflicts and their involvement in militarized or armed groups not provided for by the laws of Ukraine. Under the amended Article 30, the State should take all necessary measures to prevent the recruitment and use of children in hostilities and armed conflicts, to identify such children, and to release them from military service. It also designates the governmental body responsible for dissemination of information on the topic.

Furthermore, the Law on Amendments introduces Article 30(1) into the Law on the Protection of Childhood. Article 30(1) applies to children in zones of hostilities and armed conflict, as well as to children who have suffered as a result of hostilities or armed conflict.

The Law on Amendments also amends Article 32 of the Law on the Protection of Childhood. The amended article obliges the State to take all necessary and possible measures to search for children who have been illegally taken abroad, including in connection with circumstances related to hostilities and armed conflict.

Finally, the Law on Amendments introduces a new sentence in Article 4(1) of the Law on Ensuring the Rights and Freedoms of Internally Displaced Persons, which provides that every displaced child, including those who are unaccompanied, receives a certificate for internally displaced persons following the appropriate procedure.26

2017

Ukraine

Resolution of the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine on Adopting the Procedure for Granting the Status of a Child Affected by War and Armed Conflict27

Based on Article 30(1) of Ukraine's Law on the Protection of Childhood, on 5 April 2017 the Cabinet of Ministers introduced a new legal status for children who suffer from the effects of the armed conflict in Ukraine. The preamble of the Procedure states that it has been elaborated to protect children who experience any type of violence in the course of ongoing hostilities in the Ukraine.

The Procedure lays down the mechanism for obtaining the status of a child affected by war and armed conflict. Under Article 3 of the Procedure, this status can be obtained by any individual who, as a result of hostilities, suffers physical injuries, physical or sexual abuse, kidnapping, recruitment in armed groups, illegal detention or captivity, or psychological abuse, and who has not attained the age of 18 at the time the events occur. In Article 2(3), the Procedure gives a very broad definition of psychological violence that can be understood as any kind of suffering experienced due to living in, or relocation or displacement from, the conflict area. The remaining provisions set out the list of documents necessary to obtain the status, the authorities responsible for the approval of the documents, and the persons authorized to submit such documents in the interest of a child.

United Arab Emirates

Federal Decree Law No. 12 of 2017 on International Crimes28

On 18 September 2017, the president of the United Arab Emirates promulgated Federal Decree Law No. 12 of 2017 on International Crimes.

The Law establishes national jurisdiction over four categories of international crimes. Chapter I contains a provision on the subject matter jurisdiction of the State courts under the Law. Chapter II provides the definition of genocide and crimes against humanity, as well as the applicable punishment for certain modes of the commission of those crimes. Chapter III provides the definition of a number of war crimes, committed in both international and non-international armed conflict, and provides the applicable punishment for each crime. Chapter IV provides the definition of the crime of aggression and the applicable punishment.

In relation to the protection of children, Article 2(5) of the Law criminalizes as an act of genocide the forcible transfer of children of a protected group to another group. Article 6(1) of the Law criminalizes as a crime against humanity acts of enslavement, including trafficking in persons, in particular women and children.

Finally, Article 17 criminalizes as a war crime the compulsory or voluntary conscription or enlistment of children under the age of 15 into armed forces or their use for active participation in hostilities. The provision applies in, or in connection with, both international and non-international armed conflicts.

2018

Bahrain

Decree Law No. 44 of 2018 on International Crimes29

Decree Law No. 44 of 2018 on International Crimes entered into force in Bahrain on 6 October 2018.

The Law establishes national jurisdiction over four categories of international crimes. Chapter 1 contains general provisions on the application of the Law, Chapter 2 contains provisions relating to individual criminal responsibility, and Chapter 3 relates to the definition of the crimes of genocide and crimes against humanity. Chapter 4 contains provisions on war crimes, in particular war crimes consisting in the use of prohibited methods and means of warfare, war crimes against persons, war crimes against property and other rights, and war crimes against humanitarian missions and distinctive emblems. Chapter 5 contains provisions on the crime of aggression.

In relation to the protection of children, Article 13(e) of the Law criminalizes as a crime against humanity acts of enslavement, including trafficking in persons, in particular women and children. Article 15(a) of the Law criminalizes as an act of genocide the forcible transfer of children of a protected group to another group.

Article 23 criminalizes the compulsory or voluntary conscription or enlistment of children under the age of 18 into armed forces or their use for active participation in hostilities. The provision applies in, or in connection with, both international and non-international armed conflicts.

Niger

Law No. 2018-74 on the Protection and Assistance of Internally Displaced Persons30

On 10 December 2018, the National Assembly of Niger approved the Law on the Protection and Assistance of Internally Displaced Persons. The Law contains specific provisions on the protection and assistance of displaced children.

Article 2(1) of the Law defines internally displaced persons as persons or groups of persons who have been forced or obliged to flee or abandon their homes or places of habitual residence, in particular after, or in order to avoid the effects of, armed conflicts, situations of widespread violence, human rights violations, and/or natural or man-made disasters, and who have not crossed the territorial borders of Niger. Article 2(11) of the Law defines a child as an individual under the age of 18.

Article 19 of the Law contains specific provisions on the assistance of children and their treatment in according to their specific needs related to health, nutrition, education, access to health care in general and in cases of sexual violence.

Article 30(2) of the Law criminalizes the recruitment of internally displaced children and forcing or permitting them to participate in hostilities. In addition, Article 30(3) provides for the criminalization of the abuse or exploitation of displaced children, and Article 30(4) criminalizes the kidnapping, hostage taking, sexual slavery or any other form of sexual exploitation of internally displaced persons, and in particular internally displaced children.

2019

Afghanistan

Law on Protection of Child Rights31

On 5 March 2019, the president of Afghanistan endorsed the Law on Protection of Child Rights, ratified by the Cabinet of Afghanistan on the same day.

Article 3 of the Law defines a child as a person who has not completed the age of 18.32 Under Article 12 of the Law, every child has a number of basic rights, including the right to live; to be protected from any forms of discrimination; to health and access to health-care services; to learning and education; to freedom of speech and expression; to family; to prevention from recruitment in military and semi-military services; to protection against any form of torture, excruciation, inhuman or insulting punishment, and cruel actions; to benefit from the rights of the suspect and the accused, and from fair trial; to be protected from being used in immoral or sexual acts; and to be protected against kidnapping and trafficking. These rights are elaborated on in subsequent provisions.

Article 34 of the Law provides for an obligation of relevant ministries and government organizations to undertake necessary measures to achieve physical and mental rehabilitation of a child who is harmed, inter alia, due to armed conflicts.

Article 75 of the Law prohibits the recruitment of children and using them in military forces, including the Ministries of Defence and Interior Affairs and the General Directorate of National Security Forces, or forces of other organizations with a military structure. Such recruitment or use is considered a violation of a child's human rights and is subject to criminal prosecution.

Article 76 of the Law provides an obligation to relevant ministries and governmental organizations to observe IHL, especially rules related to children. Such ministries and organizations are obliged to prevent the use and recruitment of individuals who have not completed the age of 18 in the armed forces and their participation in armed conflicts. They are also obliged to take necessary action to ensure the protection of children affected by armed conflict.

Kyrgyzstan

Criminal Code of the Kyrgyz Republic33

The new Criminal Code of the Kyrgyz Republic was adopted by the Parliament on 2 February 2017 and entered into force on 1 January 2019.

Article 182 of the Criminal Code prohibits the transfer of individuals under the age of 18 into zones of armed hostilities or armed conflict on the territory of another State, including by a parent or another person entrusted with responsibility over the minor.

The Criminal Code introduces its new Chapter 53, titled “War Crimes and Other Violations of Laws and Customs of Warfare”. Article 392(6) of this Chapter prohibits the recruitment of individuals under the age of 18 in the armed forces or permitting such individuals to take part in hostilities. In addition, Article 392(7) criminalizes the recruitment of individuals under the age of 18 in armed groups that are distinct from the armed forces of the State, or the use of such individuals in hostilities as members of such armed groups.

Myanmar

Child Rights Law34

On 23 July 2019, the president of Myanmar enacted the Child Rights Law.

Under Article 3(d) of the Law, a child is anyone under the age of 18. Chapter 17 of the Law is entitled “Children and Armed Conflict” and contains several provisions dealing with children affected by armed conflict. Article 60 sets out the obligation of State bodies and agencies, as well as of non-State entities, in relation to the protection of children affected by armed conflict and their rights. Such obligations include preventing physical and sexual violence and the recruitment and use of children in armed conflict, and ensuring the treatment, rehabilitation, education and reintegration of children affected by armed conflict. In addition, under Article 60(b), all children affected or displaced by armed conflict are considered victims.

Article 61 of the Law criminalizes the recruitment and use of children in armed conflict, physical or sexual violence against children, attacks on educational institutions or hospitals, and obstructing the receipt of humanitarian assistance. Article 62 of the Law sets out the rights of children in armed conflict, including their entitlement to protection against physical violence, neglect, exploitation and sexual violence, abduction and detention, as well as their right to assistance as victims affected by armed conflict.

Article 63 of the Law prohibits the recruitment or enlistment of individuals under the age of 18 into the armed forces of the State or their use in hostilities. Article 64 of the Law prohibits the recruitment or use of individuals under the age of 18 in hostilities by non-State armed groups.

Philippines

Special Protection of Children in Situations of Armed Conflict Act35

The Special Protection of Children in Situations of Armed Conflict Act was promulgated in the Philippines on 10 January 2019 and came into force on 25 January 2019. Recognizing the vulnerable status of children, especially those in situations of armed conflict, the Act declares children as “Zones of Peace” and mandates the State to provide them with special protection.

Section 2 provides that it is the policy of the State to provide special protection to children in situations of armed conflict from all forms of abuse, violence, neglect, cruelty, discrimination and other conditions prejudicial to their development. It also provides, inter alia, for the full implementation of IHL and human rights treaties providing for the protection of children; for the respect of the human rights of children at all times; for the prevention of the recruitment and use of children in armed conflict;36 for the provision of effective protection and relief to all children in situations of armed conflict; and for ensuring the right to participation of children affected by armed conflict in all of the State's policies, actions and decisions concerning children's rescue, rehabilitation and reintegration.

In accordance with Section 3, the Act applies to all children involved in, affected by, or displaced by armed conflict.

Under Section 5(g) of the Act, a child is defined as a person below the age of 18 or a person of 18 years or older who is unable to fully take care of or protect himself or herself or act with discernment because of physical or mental disability. Furthermore, Sections 5(i), (j) and (k) define “children affected by armed conflict”, “children involved in armed conflict” and “children in situations of armed conflict” respectively.

Section 7 of the Act provides a broad range of rights applicable to children in armed conflict, most significantly the right to be treated as a victim. It also guarantees the protection of the civil, political, economic and social rights of children.

Section 8 of the Act specifies the measures that the State is to take to prevent the recruitment, re-recruitment, use, displacement of, or grave violations against children involved in armed conflict.

Section 9 of the Act provides for criminal sanctions for a number of violations committed against children in the context of armed conflict. These include killing, torture, rape and gender-based violence, cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, abduction or hostage-taking, the use or involvement of children in armed conflict in any capacity, refusal or denial of humanitarian access or assistance and food blockading, as well as arrest, arbitrary detention or unlawful prosecution of children allegedly associated with armed groups or government forces. Sections 13–21 provide for the investigation and prosecution of the acts penalized under the Act.

Section 22 directs the State to institute policies, programmes and services for the rescue (including the recovery from armed groups or government forces), rehabilitation and reintegration of children in situations of armed conflict.

Section 28 of the Act provides for dismissal of criminal cases against children involved in armed conflict, and their immediate referral to the social welfare authorities for rehabilitation and reintegration programmes. Additionally, Section 31 provides for the retroactive application of the law to persons who have been convicted or are serving sentence at the time of the effectivity of the Act but who were below 18 at the time of the commission of the offence.

Case law

Austria

Supreme Court Judgment 13.02.2018 14 Os 116/17s37

On 13 February 2018, the Austrian Supreme Court confirmed the conviction (issued by the Regional Criminal Court of Graz on 2 June 2017) of four defendants (two couples) for, among other charges, torturing their eight children by taking them into a territory controlled by the non-State armed group Islamic State (IS).

In December 2014, the four defendants travelled to Syria with their children, aged between 2 and 11 years. There they lived in territory controlled by IS, where the children were exposed to violent propaganda and extreme acts of violence on a daily basis, including public executions in the form of beheadings and stoning. The children were also subjected to a system of radical Islamic education. The defendants were charged with and found guilty of psychological torture pursuant to Article 92(1) of the Austrian Criminal Code. They were also convicted for membership of a terrorist organization and of a criminal organization. The Supreme Court, however, repealed the first-instance decision on trial costs, which has been sent back for a new hearing before the Regional Criminal Court of Graz.

Canada

Désiré Munyaneza Case, Quebec Court of Appeals, 22 May 201438

On 7 May 2014, the Court of Appeal of Quebec upheld the conviction of Désiré Munyaneza, a Rwandan citizen arrested and prosecuted in Canada under the Crimes against Humanity and War Crimes Act of 2000, for seven counts of genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes committed during the 1994 Rwandan genocide.

The appeal arose from the judgment delivered by the Superior Court of Quebec in 2009,39 which found Munyaneza guilty of war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide. After classifying the conflict in Rwanda between 1 April and 31 July 1994 as non-international, the Court found that Munyaneza had intentionally murdered, sexually assaulted and looted the homes of a number of individuals from the Tutsi ethnic group who had not participated directly in hostilities. Many of the victims were children or below the age of 18 years.

The Court of Appeals affirmed Munyaneza's sentence of life imprisonment.

Colombia

Decision No. C-007, Constitutional Court, 1 March 201840

Judgment C-007-18 was delivered by the Colombian Constitutional Court on 1 March 2018.

The Constitutional Court reviewed Amnesty Act 1820 of 2016 (Ley 1820 de 2016), which concerned the realization of one of the points of the 2016 Peace Agreement concluded between the Colombian government and the former armed group the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia, FARC). Under this point, most members of FARC were granted amnesties, with the exception of those accused of having committed war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide, which may include extrajudicial executions, hostage taking and other serious deprivations of liberty, torture, enforced disappearance, rape and other forms of sexual violence, child abduction and recruitment of minors.

In its analysis, the Constitutional Court reiterated its position that the war crime of child recruitment includes both direct and indirect types of participation in armed conflict, which reflects the position of the International Criminal Court on the matter.

Additionally, the Court stated that as of 25 June 2005 (the date of entry into force in Colombia of the Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the Involvement of Children in Armed Conflict), the age limit for the prohibition of child recruitment in Colombia is 18 years. Before the entry into force of the Optional Protocol, it was prohibited to recruit children under the age of 15 years. In both cases, the Court based its position on an analysis of IHL standards, doctrine, customary IHL and the principle of the best interest of the child. On this basis, the Court concluded in para. 484 of the Judgment that the prohibition on recruiting children under the age of 18, applicable in Colombia as of 25 June 2005, “is a matter of customary law”.

Lastly, the Constitutional Court concluded that child recruitment was a crime not eligible for amnesty or a decision not to bring criminal prosecution against former FARC members under Amnesty Act 1820.

Germany

Decision OVG 10 S 43.19, Higher Administrative Court for Berlin-Brandenburg, 6 November 201941

On 10 July 2019, the Berlin Court of First Instance issued a decision, ruling that Germany's Ministry of Foreign Affairs should repatriate from the Al-Hol camp in Syria the German wife and three children of a suspected fighter of the non-State armed group Islamic State. The Court held that the children's right to be repatriated back to Germany stems directly from Article 2(2) of the German Constitution, on the right to life and physical integrity. The decision was appealed.

The Higher Administrative Court for Berlin-Brandenburg rendered the final decision on the case on 6 November 2019. The Court decided that Germany is under an obligation to return the children to Germany, together with their mother, in order to protect the integrity of the family unit. It did not question that the respondent (the Federal Republic of Germany) has in principle a wide margin of appreciation as to how it protects fundamental rights and does not require a specific procedure for the return. It noted, however, that Germany has previously found ways to repatriate children from Al-Hol, despite its lack of access, through the assistance of “a non-governmental organisation” (para. 48). It also held that circumstances will make return difficult, but not impossible (para. 49).

In relation to the repatriation, the Court recognized the right and duty of the State to protect citizens on German territory in case of a concrete risk. However, it did not consider it sufficiently concrete that the federal public prosecutor is conducting an investigation against the applicant in the case on suspicion of membership of a terrorist organization abroad, or that “IS women” in general may have committed war crimes.

Other relevant highlights

Canada

Regulations Implementing the United Nations Resolutions on Mali, SOR/2018-20342

On 9 September 2017, the UN Security Council adopted Resolution 2374 creating a sanctions regime targeting actors derailing the Agreement for Peace and Reconciliation in Mali. The Regulations adopted by the government of Canada on 10 October 2018 implement into Canadian domestic law the sanctions regime imposed by the Security Council. The Regulations prohibit persons in Canada, and Canadians outside Canada, from knowingly dealing in the property of certain persons designated by the Security Council. These measures apply to persons responsible for or complicit in, or having directly or indirectly engaged in, the use or recruitment of children by armed groups or armed forced in violation of international law.

Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS)

ECOWAS Child Policy 2019

The ECOWAS Child Policy 2019 is a legally binding regional policy that provides a broad-based structure and policy direction for ECOWAS member States in their common regional and international aspirations towards fulfilling child rights in West Africa. The imperative for a regional child policy stems from ECOWAS member States’ commitment to fulfilling their obligations towards children in accordance with the Revised ECOWAS Treaty of 1993 and its associated instruments. Article 4 of the Treaty guarantees the fundamental principles of human rights in accordance with the provisions of the African Charter on Human and People's Rights. With respect to child well-being, all ECOWAS member States have ratified and domesticated the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989) and the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child (1990). A child is defined as any person below the age of 18, unless the laws of a particular country set the legal age for adulthood lower.

The Child Policy raises a number of concerns about the vulnerability of children affected by armed conflict or other crisis situations in West Africa. These concerns include internal and cross-border displacement and difficulties in tracing children and unifying them with their families. In addition, children suffer serious consequences as a result of frequent violations of treaty and customary rules of IHL – sexual violence, indiscriminate or disproportionate attacks, detention, unlawful recruitment, unlawful denial of access to humanitarian assistance, and attacks on health-care and educational facilities. According to the Child Policy, activities of non-State armed groups against children, such as abduction, sexual and gender-based violence, or the use of children in acts deemed to be terrorist, are a matter of grave concern for the region. Another concern raised by the Policy is severe traumatization and possible stigmatization suffered by children in post-conflict situations and the complexity of providing appropriate rehabilitation and reintegration for child survivors of armed conflict.

In this respect, Goal 3 of the Policy is the protection of children from all forms of violence, abuse and exploitation, as well as providing them with access to prevention and response services. Objective 1 of Goal 3 is the adoption by each ECOWAS member State of relevant laws and policies, as well as the establishment of institutions to support prevention and response actions that will protect children in the region from violence, abuse and exploitation in compliance with international and regional legal frameworks. In this respect, member States are required to ratify and domesticate all relevant international legal instruments establishing standards of child protection within and outside the context of an armed conflict, to formulate and implement appropriate national policies and action plans in accordance with specific commitments in relation to the protection of children affected by armed conflict, and to establish relevant national mechanisms.

Objective 2 of Goal 3 requires States to ensure that international standards are met in relation to children in detention, and that detention is only used as a last resort. To that end, States are required to implement international standards relating to juvenile justice and promote specific policies for children in conflict, to end detention of children for immigration purposes, and to establish functioning alternatives to detention.

Objective 4 of Goal 3 requires key community institutions to develop increased positive attitudes to social protection programmes for children.

France

Instruction on the Care of Minors on Their Return from Terrorist Groups’ Areas of Operations (in Particular the Iraqi–Syrian Area)43

The Instruction on the Care of Minors on Their Return Home from Terrorist Groups’ Areas of Operations was adopted in France on 23 February 2018.

The Instruction organizes the care of minors upon their return to French territory from terrorist groups’ areas of operations and provides for specific support adapted to their individual situations. The system is largely based on existing legislation and seeks to mobilize all State services on this issue, to improve their coordination with the departmental councils responsible for the care of these children, and to specify how the existing legal mechanisms interact in order to provide the most adapted support and ensure longer monitoring. The Instruction specifies how the children are to be taken care of upon their return, in particular in terms of both physical and medico-psychological assessment and support, schooling, specific training of professionals in charge of support, coordination, and assessment and monitoring guidelines. A monitoring committee for the system is set up under the supervision of the Ministry of Justice and the Ministry of Solidarity and Health, the secretariat of which is provided by the General Secretariat of the Inter-Ministerial Committee for the Prevention of Crime and Radicalization.

Norway

Action Plan against Radicalization and Violent Extremism44

On 10 June 2014, the government of Norway published an Action Plan against Radicalization and Violent Extremism. The Action Plan aims at preventing radicalization and at giving returning foreign fighters and their families necessary and special follow-up.

The Action Plan identifies the cases in which the Ministry of Children, Equality and Social Inclusion and other governmental organs will be responsible for undertaking measures in relation to children and youths in danger of, or having suffered as a result of, radicalization and violent extremism. Preventive measures include holding dialogue conferences for young people, support for voluntary organizations working to prevent radicalization and violent extremism, developing a scheme to provide guidance to parents and guardians who are concerned for their children in this respect, and a number of measures to prevent radicalization and recruitment through the Internet. Reactive measures include developing trauma-focused treatment for returning children and youths who have taken part in military actions abroad as foreign fighters or are family members of foreign fighters.

Syria

Law No. 11, Addendum to the Penal Code Regarding the Involvement of Children in Hostilities45

On 24 June 2013, the Syrian Parliament approved an amendment to the Syrian Criminal Code in relation to the involvement of children in hostilities. The Syrian Arab Republic ratified the Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the Involvement of Children in Armed Conflict on 17 October 2003. The amendment modifies Article 488 of the Criminal Code by establishing in Article 1(1) a punishment of ten to twenty years’ temporary hard labour and a fine for any person recruiting a child under the age of 18 for the purpose of involving him in hostilities or in other related acts such as carrying arms, equipment or ammunition. The same sanction applies to persons recruiting a child to use him as a human shield or for any form of assistance to the perpetrators or other acts in hostilities. A penalty of lifetime forced labour is foreseen if the child suffers from a permanent disability as a result of his participation in hostilities, or if he was sexually abused or given drugs while being recruited. Under Article 1(2), the death penalty is foreseen for cases where a child dies as a result of his involvement in hostilities.

- 1In order to assist States, the ICRC Advisory Service proposes a multiplicity of tools, including thematic fact sheets, ratification kits, model laws and checklists, as well as reports from expert meetings, all available at: www.icrc.org/en/war-and-law/ihl-domestic-law (all internet references were accessed in January 2020).

- 2For information on national implementation measures and case law, please visit the ICRC Database on National Implementation of IHL, available at: www.icrc.org/ihl-nat.

- 3To view the full list of IHL-related treaties, please visit the ICRC Treaty Database, available at: https://ihl-databases.icrc.org/ihl.

- 4Available at: https://tinyurl.com/rfzps9

- 5Available at: https://tinyurl.com/yb3fzjh8

- 6Available at: https://tinyurl.com/y9fl7l6c

- 7See above note 2.

- 8Available at: https://tinyurl.com/ugjbasc.

- 9The text of Resolution 1612 is available at: https://tinyurl.com/rdr6ko.

- 10Available at: https://tinyurl.com/u8m25tu.

- 11Available at: https://tinyurl.com/w4oox64.

- 12UN Committee on the Rights of the Child, State Party Report: Estonia, UN Doc. CRC/C/OPAC/EST/1, 3 June 2016, para. 28, available at: https://tinyurl.com/soeswkc.

- 13Available at: https://tinyurl.com/velb458.

- 14Available at: https://tinyurl.com/u7tfchg.

- 15Available at: https://tinyurl.com/sc9k3nv.

- 16See above note 9.

- 17Available at: https://tinyurl.com/vgjqs5y.

- 18India has been a party to the Convention on the Rights of the Child since 11 December 1992, and to its Second Optional Protocol since 30 November 2005.

- 19Available at: https://tinyurl.com/ue6qg2x.

- 20Available at: https://tinyurl.com/sgvmdgw.

- 21Available at: https://tinyurl.com/reh256n.

- 22Available at: https://tinyurl.com/qsbsp7y.

- 23Available at: https://tinyurl.com/ycr29fes.

- 24Available at: https://tinyurl.com/rh9j38b.

- 25Available at: https://tinyurl.com/sjmc5kk.

- 26In this regard, it should be noted that under Article 1(1) of the Law of Ukraine on Ensuring the Rights and Freedoms of Internally Displaced Persons, internally displaced persons are Ukrainian citizens, as are foreigners and stateless persons who are legally in the territory of Ukraine and have the right to permanently reside there, and who have left behind or abandoned their place of residence as a result of, or to avoid the negative consequences of, conflict, temporary occupation, widespread violence, violation of human rights, or natural or man-made disaster.

- 27Available at: https://tinyurl.com/suhxofc.

- 28Available at: https://tinyurl.com/tkzaalz.

- 29Available at: https://tinyurl.com/tr4r52x.

- 30Available at: https://tinyurl.com/wkk5xuj.

- 31Available at: https://tinyurl.com/t7cgvzd.

- 32This means that adulthood is attained on the individual's 19th birthday.

- 33Available at: https://tinyurl.com/wv4sbc8.

- 34Available at: https://tinyurl.com/qpg5ynu.

- 35Available at: https://tinyurl.com/rgsruhd.

- 36Section 5(c) of the Act defines “armed conflict” as armed confrontations occurring between government forces and one or more armed groups, or between such groups, arising in the Philippine territory. This includes activities which may lead up to or are undertaken in preparation for armed confrontation or armed violence that put children's lives at risk and violate their rights. The Act does not seem to apply to children affected by international armed conflict.

- 37Available at: https://tinyurl.com/s5lxtzp.

- 38Available at: https://tinyurl.com/supdxo6.

- 39Quebec Superior Court, Désiré Munyaneza Case, 22 May 2009, available at: https://tinyurl.com/wajz465.

- 40Available at: https://tinyurl.com/tlbc5gw.

- 41Available at: https://tinyurl.com/ved3scp.

- 42Available at: https://tinyurl.com/rcxualq.

- 43Available at: https://tinyurl.com/wrugowt.

- 44Available at: https://tinyurl.com/rewkgsl.

- 45Available at: https://tinyurl.com/smb6rn9.