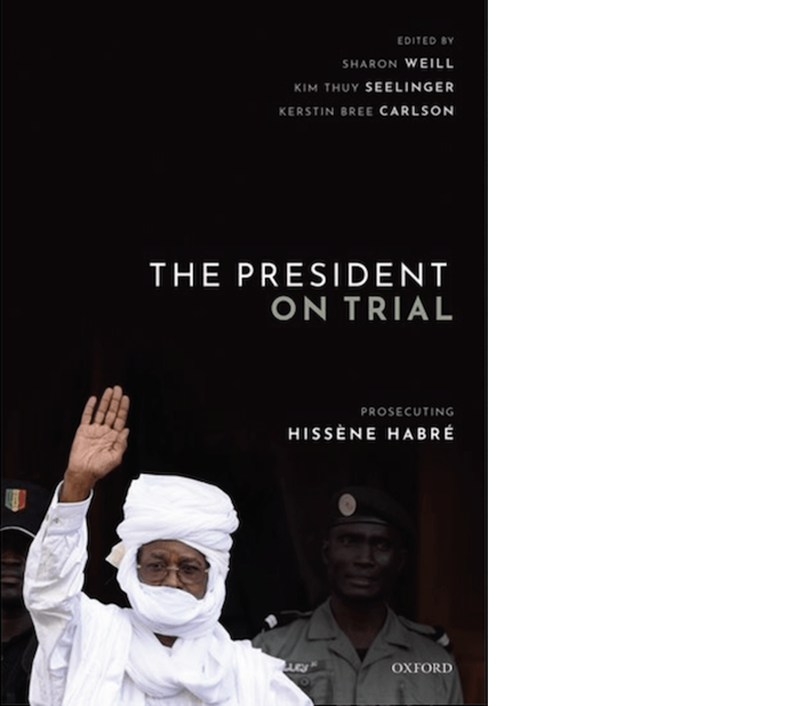

The President on Trial: Prosecuting Hissène Habré

In May 2016, Hissène Habré, president of Chad from 1982 to 1990, was convicted by the Extraordinary African Chambers (EAC) – a hybrid tribunal established in the courts of Senegal on the basis of the principle of universal jurisdiction – of war crimes, crimes against humanity and acts of torture. His conviction was upheld by the EAC's Appeals Chamber on 27 April 2017,1 and he was sentenced to life in prison. It was the first time that an African defendant was convicted of war crimes on African soil, and the first time that a deposed head of State faced justice for the atrocities committed by his security forces against his own population on the continent. The Habré trial was the culmination of twenty years of efforts by Chadian victims’ organizations, supported by NGOs like Human Rights Watch (HRW), to bring their former president to justice. It happened against considerable odds, an unlikely and unprecedented ending to a long judicial and political saga.

ICRC Library

The “Librarian's Pick” is a regular section of the Review in which one of the International Committee of the Red Cross's (ICRC) librarians picks and writes about their favourite new book relating to international humanitarian law, policy or action, which they recommend to the readers of the journal.

The ICRC Library welcomes researchers interested in international humanitarian law (IHL) and the institution's work throughout the years. Its online catalogue is the gateway to the most recent scholarship on the subject, documents of diplomatic and international conferences, all ICRC publications, rare documents published between the founding of the ICRC and the end of the First World War, and a unique collection of military manuals. The Library Team also publishes research guides in order to help researchers access the full texts of the most relevant and reliable sources in the field of IHL and the ICRC, as well as a comprehensive IHL Bibliography, with three issues every year.

The online catalogue is available at: library.icrc.org. For more information on the research guides, see: blogs.icrc.org/cross-files/category/research-guide. To subscribe to the IHL Bibliography, email library@icrc.org with “IHL Bibliography subscription” in the subject line.

Regarded as a landmark achievement in international justice, the Habré trial could become a milestone in the fight against global impunity – or it could remain an exception, brought about by the sheer determination of victims’ advocates just as the right political stars finally aligned. This leaves practitioners and scholars with no guarantees as per the legacy of the trial, but with many interrogations regarding its successes, shortcomings2 and potential replicability. The President on Trial: Prosecuting Hissène Habré is a volume rooted in this uncertain space. It manages to capture the hopes and insights of the trial's protagonists at the same time as it propels forward the scholarship on the trial's significance and legacy. This approach hinges on an innovative methodology that sparks a conversation between academic authors and the trial's participants.

The first part of the volume is a collection of twenty-six first-person accounts by protagonists of the trial. The contributions are based on interviews conducted by the volume's editors, mixing voices from inside and outside the court. They alternate between local and international perspectives, between activist, official and academic voices, and include accounts from both the prosecution and the defence's3 standpoints. Though quite short, the individual contributions are often remarkably introspective and thought-provoking, leaving the reader with the sole frustration of being unable to ask follow-up questions. The protagonists present factual accounts of their individual contributions to the trial, but personal hopes, wishes and frustrations do arise as well. Many recount the challenges they faced, from political obstruction to financial and time constraints. This succession of voices creates a powerful narrative, painting a clear picture of the trial as an uphill battle. It delves into processes and participants, giving the reader an invaluable case study of the operationalization of international criminal justice. The selection includes some well-known actors – like Reed Brody from HRW,4 presented as the public face of the trial in the Anglophone world – but the book gives most of the space to lesser-known protagonists, in line with the editors’ wish to “bring local experience and knowledge out of Dakar and to the world”.5 These include former trial officials that occupied a wide range of positions: judges, a clerk, and multiple administration, outreach and finance officials. EAC Investigating Judge Jean Kandé speaks about the limits to judicial cooperation that he faced in the case, which led to Habré being the sole defendant on trial.6 Franck Petit, former team leader for the Outreach Consortium on the EAC, discusses the challenges of bridging the distance between the Chadian population and the trial taking place in Dakar.7

The most memorable contributions, however, are arguably those belonging to the coalition of victims, lawyers and activists that drove the investigation and spearheaded the case, notably Souleymane Guengueng8 and Jacqueline Moudeina.9 The Habré trial is systematically presented as a “victim and NGO-driven case”, and the writings of these contributors show what that entailed. They speak of the victims’ determination and fears, of reprisals and community backlash, of the difficulty of gaining access and trust and of ensuring the security of civil parties and witnesses during the trial. Moudeina notably recounts the stories behind the testimonials of the women victims of sexual violence. Her contribution enlightens us as to why such crimes were not part of the original charges brought against Habré and how they finally came to light, leading to a verdict that is regarded as a breakthrough for the prosecution of sexual violence in international criminal justice.

The second part of the book follows a more traditional path. It is a collection of seventeen academic contributions by international criminal law scholars, divided into four categories according to their outlook on the discipline. These contributions investigate the legal issues that are central to the trial, including the non-retroactivity of criminal law, the jurisdiction and legitimacy of the EAC, the prosecution of sexual violence, victim participation, hybrid courts, and the attribution and allocation of reparations. They paint a broader picture of the future of transitional justice on the African continent, and of the mechanisms and politics at play. They are at their most impactful when they echo the first-person accounts of the book and explore the theoretical and practical ramifications of the Habré trial. Dov Jacobs’ contribution on the position of the defence in hybrid tribunals, for example, resonates with the arguments put forward by Habré's lawyer Mounir Ballal as it looks at the implications of the victim-oriented trend of international criminal justice for the rights of the defence.10 Sarah Williams’ chapter is a welcome external view on the approach and content of the amicus curiae brief on sexual violence submitted to the EAC to advocate for a revision of the charges against Habré.11 Her analysis follows a first-person contribution by some of the authors of the amicus curiae brief included in the first part of the book12 and represents one of the many contributions exploring the impact of peripheral actors or mechanisms on the trial.

Given its unconventional methodology, the book benefits from a clear, well-thought-out structure. Each section has a specific introduction which brings to light the stakes of the contributions to come and the logic behind their articulation. The book opens with chronologies and graphs that provide the reader with the contextual information needed to follow a necessarily fragmented narrative, told as it is by a multitude of actors. This kaleidoscopic take on the trial is in fact the book's major strength. Read in connection with the others, each contribution takes on new meanings. Stories are corroborated, concerns are shared, and at times viewpoints collide; the book keeps all the plates spinning smoothly. Inviting more research, it provides practitioners with a series of leads and clues, rather than with a definitive conclusion on the legacy of the trial. Ultimately, The President on Trial is a distinctive and timely read on an emblematic case. It captures the current preoccupations and hopes of advocates and practitioners of international criminal justice, at a time marked by a much-discussed African backlash against the International Criminal Court. The book looks back on the history of the Habré trial but remains rooted in the present and turned towards to the future, aiming to explore – and perhaps challenge – assumptions that the trial is doomed to be a precedent with no future.13

- 1With one notable exception: a case of personal commission of rape, of which he was acquitted on procedural grounds.

- 2In particular, the lack of distribution of the retributions awarded to victims, to this day, is mentioned by many of the volume's contributors. The lack of cooperation with the EAC by Habré also raises questions relative to the rights of the defence.

- 3The absence of Habré's chosen counsel as well as of Senegalese and Chadian government officials is mentioned up front with regret by the editors. The defence's perspective is explored in a contribution by Hélène Cissé (“Defending Hissène Habré in Senegal during the Early Years”), who participated in Habré's defence in 2000–01 before the criminal court in Dakar, and in a chapter by Mounir Ballal (“Defending Habré”), one of Habré's court-appointed lawyers at the EAC. It is also represented in an excerpted testimony that sees Daniel Fransen, Belgian investigating judge, answer Mounir Ballal's questions (“The Belgian Investigation of the Habré Regime: Excerpt of Trial Testimony by Daniel Fransen, Belgian Investigating Judge”). To include the voice of Hissène Habré himself – as he remained silent during the trial, refusing to recognize the legitimacy of the EAC and to collaborate with his court-appointed lawyers – the editors have included excerpts from his 2011 interview with Senegalese reporters from the newspaper La Gazette (“In His Own Words: An Interview with Hissène Habré”).

- 4See Reed Brody, “Tenacity, Perseverance, and Imagination in the ‘Private International Prosecution’ of Hissène Habré”, in The President on Trial, pp. 39–7.

- 5The President on Trial, p. 2.

- 6See Judge Jean Kandé, “Investigations in Senegal and Tchad: Cooperation and Challenges”, in The President on Trial, pp. 81–89.

- 7See Franck Petit, “Outreach for the EAC”, in The President on Trial, pp. 186–193.

- 8See Souleymane Guengueng, “Documenting Crimes and Organizing Victims in Chad”, in The President on Trial, pp. 31–3. Guengueng is the founder of the Association of Victims of Political Repression in Chad, a civil party in the Habré trial, and director of the Souleymane Guengueng Foundation.

- 9See Jacqueline Moudeina, “From Victim to Witness and the Challenges of Sexual Violence Testimony”, in The President on Trial, pp. 118–124. The first woman to practice law in Chad, Moudeina was the victims’ legal counsel before the EAC and is the former president of the Chadian Association for the Promotion and Defence of Human Rights.

- 10See Dov Jacobs, “Hybrid Justice and the Rights of Defence: Existence at the Periphery”, in The President on Trial, pp. 252–264.

- 11See Sarah Williams, “Hybrid Courts and Amicus Curiae Briefing”, in The President on Trial, pp. 351–364.

- 12See Kim Thuy Seelinger, Naomi Fenwick and Khaled Alrabe, “Can We Be Friends? Offering an Amicus Curiae Brief on Sexual Violence to the EAC”, in The President on Trial, pp. 134–141.

- 13See Ndeye Amy Ndiaye, “The Habré Trial and the Malabo Protocol: An Emerging African Criminal Justice?”, in The President on Trial, p. 240, referring to Christophe Châtelot's thesis in his article, “La condamnation de Hissène Habré: Un précédent sans lendemain?”, Le Monde, 24 May 2016.