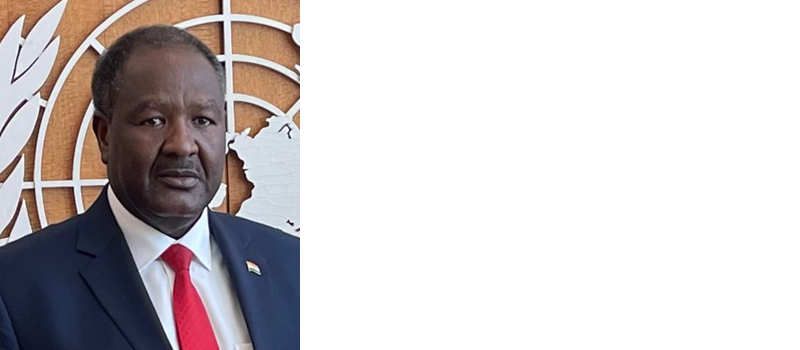

Interview with His Excellency Mr Abdou Abarry

By way of introduction, could you elaborate on the role and responsibilities you exercise in the UN Security Council on behalf of your country, Niger, which has been an elected member since January 2020? What are the main topics you have been keen to highlight under this mandate so far? Is there any progress or are there any achievements that you would like to bring to the attention of our readers?

As part of this mandate, which comes nearly forty years after the previous one, Niger is defending and promoting consideration of the challenges faced by developing countries, such as those in the Sahel. More specifically, Niger is highlighting four major challenges that are particularly acute in the Sahel.

First, there is the challenge of peace and security. The Sahel countries are facing multiple security threats, including violent extremism, terrorism and organized crime. These threats are exacerbated by instability in Libya, armed conflicts in Mali and the proliferation of armed groups, armed gangs and weapons throughout West Africa. In fact, the Sahel is now one of the most troubled regions in the world, and one of our main objectives is to draw the attention of the international community in general, and of the Security Council in particular, to this state of affairs.

Second, Niger is drawing the attention of the international community to the impact of these security threats on the development of the Sahel countries. The substantial funding that our countries are having to allocate to the fight against these threats is a precious resource that could be devoted to social and economic sectors such as education, health and agricultural development. The persistence of security threats and the urgency of addressing them mean that these important growth-producing sectors are not receiving the attention we would like to give them, which has implications for the development of our countries.

Third, there is the need to protect women and girls – especially girls. Women and young people make up nearly 52% of our population, and they are major pillars of our development. The security context described above exposes them to many forms of violence and abuse, including armed attacks, sexual violence, hostage-taking and deprivation of the right to education. It is therefore urgent that we provide effective protection for these groups.

Fourth, Niger is helping to raise the international community's awareness of the impact of climate change on peace and security. In particular, we argue that climate change is a source of instability and of security challenges.

The UN Security Council first discussed the effects of climate change and environmental degradation as an unconventional threat to peace and security in 2007. Since then, the subject has been discussed on many occasions, and the president of the Security Council has referred to it in several statements relating to the Sahel. In September 2020, when you held the presidency of the Security Council, Niger organized a ministerial meeting on the humanitarian consequences of environmental degradation, in which International Committee of the Red Cross [ICRC] president Peter Maurer participated. In your opinion, what is the link between climate change and the maintenance of international peace and security, and more specifically, how does this link translate to the Sahel region?1

It is no longer possible to deny that climate is affecting development in several regions of the world, exacerbating humanitarian and security crises. In the Sahel, where this is especially the case, climate change has intensified competition for shrinking land, fodder and water resources. This has stoked tensions between herders and farmers, and hampered peacebuilding and development in the region.

The shrinking of Lake Chad and of rivers such as the Niger owing to high temperatures and lack of rain, coupled with a population explosion, is also generating conflicts between farming and herding communities over control of these scarce resources in many countries of the central Sahel, the Central African Republic and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Terrorists are exploiting the conflict between herders and farmers to perpetrate their atrocities, taking advantage of tensions between populations.

We therefore see a direct link between the management of increasingly scarce natural resources and the question of peace and security. These issues are becoming more acute in the Sahel region, despite many of our partners still being reluctant to recognize the problem. But if there is one thing on which the Security Council agrees, it is that this is a dramatic reality in the Sahel region and the Lake Chad Basin. Numerous recent studies have shown that “climate change and conflict dynamics create a feedback loop in which the impacts of climate change create additional pressures, while conflict undermines the capacity of communities to cope”.2

Why do you believe it is important for climate change to be on the Security Council agenda as a threat to peace and security within the meaning of the UN Charter? How would you answer the criticisms of those who consider climate change a development matter rather than a security issue, claiming that responsibility for discussing and remedying it lies not with the Security Council but with specialized bodies such as the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change or the Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change? How does the work of the UN Security Council strengthen this broader institutional framework aimed at combating climate change?

Climate change and land degradation are no longer an exclusively environmental matter. They form part of a broader vision that closely links environmental objectives with economic and social development objectives, and hence with the common goals of peace, stability and collective security. Climate change is thwarting States’ development efforts, forcing us to make a connection between peace and stability on the one hand and climate change on the other. To those who are still slow to reconcile these two realities, I would respond by taking the example of the current COVID-19 pandemic, which is forcing us to change the paradigm. COVID-19 has been declared a threat to international peace and security,3 despite the existence of the World Health Organization and other entities specialized in health. This pandemic is fundamentally changing the balance of nations and the international community. Climate change is also a pandemic; it is slower, but it is more dangerous because there is no vaccine against it. Just as we did with the COVID-19 pandemic, we must see climate change as a threat to peace and security, and this must not be a divisive issue. We must work even harder to translate our knowledge into concrete policies. It is important to understand the causes, effects and complexity of climate change in order to combat them, because our aim is not simply to manage conflicts: we have a fundamental responsibility to prevent them.

In short, we believe that there is a direct link between climate change and peace and security. We therefore consider it important that the international community in general and the Security Council in particular take ownership of this issue. One of our current projects is to integrate this topic into all of our training modules and peacekeeping operations, so that we can address the consequences of climate change for peace and security while there is still time.

Niger and others have described the intersecting dynamics of conflict and climate change in the Sahel region as a “feedback loop”: instability undermines the ability of communities to cope with climate hazards, which in turn exacerbates tensions and thus increases the risk of new conflicts.4 Can you tell us more about this topic, including the most significant humanitarian effects of climate change in the Sahel and how insecurity and instability are exacerbating them? How can humanitarian action mitigate these effects and reduce security problems in the Sahel?

Our leaders have always endeavoured to highlight the impact of climate change and environmental degradation on food and nutritional security, taking the Sahel as an example. In a region where the vast majority of the population depends on agriculture, the temperature increase of 2°C by 2050 that experts are predicting could, if we are not careful, lead to a 95% increase in the number of malnourished people in West Africa, together with a 15–25% reduction in food production. Humanitarian assistance is therefore becoming essential, especially since Niger is hosting many refugees and has many internally displaced persons.

Moreover, we cannot continue to invest a considerable part of our budget in maintaining security while simultaneously dealing with the disastrous consequences of climate change. When poor populations like those in the Sahel are confronted with undernourishment and the impact of rising temperatures, we cannot continue to invest in security and at the same time hope to stem the phenomenon of rising temperatures, which impedes access to food resources and the intensification of food production. This phenomenon is aggravated by demographic factors. When more than half of the population are in need of food, and the resources available to meet their needs are insufficient, this can lead to tensions, crises and even conflict. At this point I would like to pay a heartfelt tribute to all the humanitarians who are risking their lives by working alongside us to alleviate suffering. The ICRC, for example, has always been a major humanitarian partner in the Sahel and Lake Chad regions, and we would like to thank them for their fruitful collaboration on helping people in need.

In addition to its humanitarian consequences, the conduct of hostilities has a devastating effect on the resilience of communities and their ability to adapt to climate change, through direct attacks on the natural environment, destruction of land, and greenhouse gas emissions resulting from damage to industrial infrastructure, for instance.5 Niger has drawn the attention of the Security Council to the destruction of the natural environment in armed conflicts and the need for greater respect for international humanitarian law [IHL] in order to limit environmental degradation in the Sahel.6 In your opinion, why are IHL rules on environmental protection important, and what kind of action should be taken in the region to raise awareness of and compliance with these rules?

I can use my recent experience as a representative of the African Union in the Democratic Republic of the Congo to illustrate the link between environmental degradation and conflict. When you look at Virunga Park, which was once one of the most important wildlife reserves in the world and is now decimated by the armed groups that have infested the region, you quickly understand the link between the activities of these armed groups and protection of the environment. The same situation obtains in the Sahel, particularly in the “three-border” region – that is, the borders between Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger. This is the location of the W National Park, one of the most important animal reserves in the region. In terms of biodiversity, this is the only park of its type in these three countries. When armed groups commit abuses in such an area, this automatically leads to the destruction of animal species and the illegal exploitation of natural species in defiance of international environmental rules – hence the need for the UN system to promote IHL in all armed interventions. In particular, this area of IHL must be reflected in the mandates of peacekeeping operations. Measures to improve our understanding of the correlation between conflict and the impact of climate change are essential.

The natural environment is essential to the survival of the civilian population. Destroying or damaging critical infrastructure is a threat to the environment, and can have devastating effects on environmental health. Climate-related problems are exacerbating the effects on communities that depend on these environments. We are becoming increasingly aware of our dependence on the environment for survival, which means that protecting the environment during armed conflict can no longer be an afterthought. For this reason, we have always advocated inclusion of IHL in the operations manuals of our armies. We encourage increased IHL training for public authorities, to give them a sound understanding of the effects of armed conflict on the environment and of the rules that can limit the impact of armed conflict on the environment – if they are applied.

Environmental protection needs to be addressed globally. The impact of environmental destruction and destruction of industrial infrastructure goes far beyond the region or area in which they occur. We must unite to face the effects of this destruction wherever necessary. Teaching IHL is a priority issue and one where the ICRC can count on Niger's sincere and wholehearted support.

Niger has described the “triple impact”7 of climate change, conflict and the COVID-19 pandemic in the Sahel. How has this global health crisis contributed to both highlighting and exacerbating the climate and environmental crisis, the conflicts and the peacekeeping problems in this region? Are there lessons to be learned from the COVID-19 pandemic that could strengthen the response to unconventional crises such as the climate crisis?

As I indicated earlier, the current pandemic has shown that our multilateral system is no longer fit for purpose. The COVID-19 pandemic is not just a health issue – it has been a real challenge for the entire international system. We have drawn conclusions from what has happened, and must now recognize that what was adequate seventy-five years ago has been put to the test and found wanting. Now is the time for a paradigm shift. The pandemic has brought to light a new set of threats to international peace and security that were not previously apparent to anyone. Climate change is another form of COVID-19. It may be slower, but unlike the disease there is no vaccine against it. This means that if we wait any longer before we react, it will be too late. We are therefore using the platform that the Security Council offers us to highlight the situation in the Sahel, in light of the humanitarian and security risks caused by climate change.

We would like to transpose this approach and the new attitude that we advocate vis-à-vis the pandemic to the issue of climate change. The deterioration of the climate situation in the Sahel also affects the ecosystems and environment of neighbouring countries such as Benin, Côte d'Ivoire and Togo. We believe that we must be prepared for the impact of this climate change; that is why we are drawing the attention of the international community to the link between the issues of climate change, peace, security and development in the Sahel. We are also highlighting how this link could affect other nations that currently consider themselves safe but could be exposed to the same phenomenon if we do not take the precautions needed to contain it. Within the Security Council, we are using our voice – however small it may be – to draw the attention of the international community to the need for joint and concerted action to stem the effects of climate change, of the sort we have been forced to undertake in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The UN Secretary-General recently highlighted the funding gaps for climate action, in particular the unequal distribution of funds between mitigation and adaptation. He urged donors and development banks to invest more in climate change adaptation, with a view to helping communities build resilience to climate hazards, while continuing to support existing mitigation approaches such as reducing carbon emissions.8 What do you think about this? What strategy for redistributing climate action funding would you recommend to help the Sahel cope more effectively with the combined effects of climate change and conflict?

At the risk of repeating myself, I would say that the effects of climate change have no borders. No development action can be envisaged and none of the Sustainable Development Goals can be achieved without building resilience and providing predictable funding to countries in difficulty, in order to help them restore natural capital responsibly. The failure of one member of the international community in this area will inevitably have an impact on the rest of that community. I believe that the Secretary-General of the UN, as usual, is taking a visionary approach in this direction and, as a leader, I would dare to suggest that this could work as it has with regard to the fight against the COVID-19 pandemic.

We all share responsibility for managing environmental issues collectively in order to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals. Without better adaptation and resilience-building strategies, and above all, without funding to responsibly manage and restore our natural capital, climate change in West Africa and the Sahel will continue to be a significant risk factor. I think that here too, COVID has shown us the way forward. The COVAX initiative, which has enabled the international community to pool its efforts and ensure that discoveries made mainly in the global North can benefit the countries of the South, could be duplicated so that we can show more solidarity, coherence and partnership, and revitalize multilateralism. We could follow the example of action on COVID-19 as regards the fair distribution of funds and the benefits of research, in order to help those countries that are the weakest financially and are most exposed to climate change to face these challenges, in their own interests and in the interests of the international community.

At the Security Council's recent high-level open debate on climate and security, Niger cited as an example the work done by the Climate Commission for the Sahel Region [CCSR] to strengthen the resilience of local communities.9 Could you tell us more about the achievements of this body and other regional initiatives launched by the African Union and the Sahel to address climate change? How do they tie in with the Security Council's discourse on climate and security, and how could UN agencies support and strengthen them in order to improve the effectiveness and coordination of collective action on climate change?

First of all, I would like to note and welcome the commitment of the former president of Niger, His Excellency Mr Mahamadou Issoufou, in his role as chairman of the CCSR. His chairmanship of the Commission is one of the strategic legacies he has bequeathed to us. Under his leadership and commitment, the issue of climate change has emerged in Niger as a categorical imperative. We have no choice but to fight this phenomenon with our limited means. Niger has always been very aware of the impact of climate change on the lives and existence of communities. This is why President Issoufou has been so committed to this issue – a commitment that has allowed us to achieve positive results, including the establishment of a working group made up of experts from the member countries of the Commission, the drafting and approval of the diagnostic report on climate change in the Sahel, and the establishment of the Commission's ministerial body.

To become operational, the CCSR has adopted the Sahel Region Climate Investment Plan [SR-CIP 2018–2030], with an overall budget of approximately $440 billion. The objective of the plan is to contribute to global efforts to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions, enhance the adaptation capacity and resilience of the Sahelian population, and support the livelihoods of that population. The development and adoption of this investment plan was accompanied by a mobilization and advocacy strategy, a monitoring and evaluation plan and an institutional framework. A six-part priority programme has also been developed for the period 2020–25, to boost climate investment in the Sahel.

Other achievements of the CCSR include holding the first conference of heads of State and government of the member States of the Commission, which took place on 25 February 2019. That conference was preceded by four meetings of the joint working group and three meetings of the environment ministers of the member countries. It was followed by a round table in Niamey for the financing of the SR-CIP and the Priority Programme for Catalysing Climate Investments in the Sahel [PPCI 2020–2025]. During the same conference, member countries agreed to set up a permanent secretariat that will be responsible for coordinating and monitoring implementation of the SR-CIP and the PPCI in the Sahel.

The CCSR also organized a meeting of Sahel leaders under the chairmanship of Issoufou Mohamadou in September 2019 in New York. The meeting was attended by eminent personalities and international organizations, including the Secretary-General of the UN.10

It should be stressed that these measures were in line with Niger's commitment to implementing a number of national programmes, one of the most emblematic being Operation Green Sahel. This operation consisted of regreening and reforestation programmes in Niger, aimed at stemming the encroachment of the desert into arable land. The work carried out in this context has had a positive impact, contributing to the regeneration of vegetation cover. We drew on our successful experiences at the national level to take action at the regional level, when Niger was president of the CCSR. We have also used national experience and good practice to draw the attention of the international community to the need to come together to address the devastating effects of climate change.

During the high-level debate in February 2021, Niger stressed the need to shift the focus regarding those regions most affected by the climate crisis and its effects on security – such as the Sahel – from their vulnerabilities to their regional potential in terms of “natural, demographic and cultural assets”.11 Could you explain this paradigm shift? How can we ensure that the Sahel countries become key players in the fight against the climate crisis and the risks it poses to security, for example through technological innovation and the creation of sustainable jobs in the energy and agriculture sectors?

As Niger's former prime minister Brigi Rafini so aptly pointed out at a Security Council meeting on the links between climate change and security on 21 February 2021, “too often the narratives and discourses about such areas are limited to challenges and vulnerabilities. They ignore the opportunities and potential of those regions in terms of natural, demographic and cultural assets.”12 We can take a totally different view of the situation in the Sahel. For example, the groundwater in this area constitutes the world's largest subterranean water reserves, but it is difficult to access this water because of a lack of technological resources. We can reverse this situation. In particular, we can use advanced technology to extract this groundwater, overcoming our challenges related to water scarcity, as several countries in the Middle East have done. These countries are just as dry, and also lack surface water, but they have succeeded in mastering the technology of extracting subterranean products. They are producers of food, and some of them process and even export it.

Like these countries, we have the capacity to capitalize on such opportunities through technological innovation and sustainable job creation, particularly in key sectors such as energy and agriculture. In Niger, we have the 3N Initiative [Nigeriens Nourishing Nigeriens] which is well known in the humanitarian and scientific communities. This initiative is to be encouraged, as it aims to achieve food self-sufficiency by combining innovation in the areas of agriculture, seed and fertilizers. It has shown that insufficient rainfall need not be a barrier, and that we can extract and control groundwater to boost production capacity in Niger. This programme has helped ensure that Niger is no longer classified as a country facing acute food difficulties. Poor rainfall leads to poor harvests, which deprive people of food and have a serious impact on economic growth.

We wish to send the following message to all African countries: what appears to be to our disadvantage could actually be an asset. We have the resources. It is up to us to deploy our own efforts and those of the international community to make good use of our water resources, so as to reverse the trend whereby we discuss the Sahel only in terms of challenges, lack of resources and difficulties. I think it is now time for the governments of the Sahel to use technology to make better use of our resources, so that agricultural production not only feeds our populations properly but can also be exported. We can achieve this ambition, as long as it is supported by a firm commitment and a consistent political vision. The essential leverage effect for this scaling-up requires the promotion of appropriate regional initiatives. We must move forward united, with our eyes open.

What are the main obstacles that the G5 Sahel faces in its efforts to protect the civilian population? How can the resolutions that its member States adopted at the latest G5 Sahel summit help to remove these obstacles?

Cross-border terrorism and organized crime prompted the heads of State of the G5 Sahel [Burkina Faso, Chad, Mauritania, Mali and Niger] to create the G5 Sahel Joint Force in 2017. Examples include Boko Haram, whose actions have spread beyond Nigeria to all the countries of the Lake Chad Basin. The Joint Force is composed of approximately 5,000 men and is drawn from the armed forces of each of the five countries.

The countries of the Sahel are following the example of those of the Lake Chad Basin, which have set up the Multinational Joint Task Force to deal with Boko Haram. In a similar fashion, we have pooled our efforts on the basis of an expression of genuine political will. Realizing that no one country can confront terrorism on its own, we have agreed to develop a common approach to stem this scourge. The establishment of the G5 Sahel and the Joint Force is first and foremost the expression of a political will that is to be welcomed. A review of the Joint Force's operations so far has shown it to be effective. Its kinetic ground missions have neutralized and captured suspected terrorists, freed hostages and aided people who are crossing borders to protect themselves against retaliation by armed groups and gangs.

However, quite apart from the complexities inherent in the asymmetry of these operations, obstacles are still preventing this force from becoming fully operational – including logistical and, especially, financial obstacles. While the situation is not yet fully under control, the action taken so far by the Joint Force, with the support of international forces such as the Barkhane Force and cooperation with the United States and European countries, is allowing us to gradually overcome the terrorist threat in the Sahel.

One cannot talk about the fight against terrorism in the Sahel without mentioning the dramatic situation that has prevailed in Libya for nearly ten years. The fragility of our States has been exacerbated by the security consequences of the situation in that country. This, combined with the intensification of climate change, has had an impact on the ability of our States to take sole responsibility for operations. The situation is further complicated by the lack of real commitment by the international community to the countries of the Sahel as regards the fight against terrorism, in contrast with what we have seen in other parts of the world such as the Middle East. It is taking a long time to distribute the promised funds that were supposed to be allocated to the G5 Sahel countries. Certainly, many countries are supporting military operations by providing equipment and intelligence, but what we really need is a support office capable of providing predictable and sustainable resources and support, in particular through voluntary contributions that could feed a fund dedicated to supporting both offensive activities and the development activities that will be integrated into the priority investment programme of the G5 Sahel. It was for this reason that the N'Djamena Summit requested the setting-up of a UN office dedicated to the G5 Sahel Joint Force. We believe that assessed contributions as a source of funding, within the framework of participation in such an office, would accelerate the ramp-up and empowerment of the Joint Force. Discussions on the creation of this office are currently under way in the Security Council. Implementing this measure would ensure the availability of predictable resources and thus provide certainty as to the financing of the military and development activities of the G5 Sahel.

Niger currently co-chairs the Informal Expert Group on Climate and Security of Members of the Security Council. Founded in 2020, this group is tasked with examining the operational challenges that UN missions face as a result of the security crisis, and proposing solutions. As this is a very recent initiative, could you tell us what this new body has been doing during its first year of existence? What are the current challenges? To what extent will this group improve the situation of people in the Sahel?

As noted above, one of Niger's objectives within the Security Council is to highlight the link between climate change and peace and security issues. It is in line with this objective that we have been co-chairing the Informal Expert Group on Climate and Security of Members of the Security Council since 2020. Through this role, we hope to enhance understanding of security risks related to climate change and thereby boost the effectiveness of the Security Council in fulfilling its mandate to maintain international peace and security.

Our first meeting, in 2020, addressed the situation in Somalia, when Germany was co-chairing. We have already held two meetings this year on the Sahel and South Sudan – which face environmental and security challenges almost identical to those in Somalia – and are currently drawing up the programme of work for the rest of 2021. Our goal is to increase the visibility of environmental issues and promote better consideration of them in the context of activities aimed at maintaining peace and security. We wish to ensure that those members of the Security Council who are still hesitant become fully aware of the existence of a link between these two types of issue. We are pleased that when he so kindly met with us, President Joe Biden decided that the United States would join the Group. This represents a significant step forward as regards the United States’ engagement on the climate question. We hope that the United States’ approach will stimulate the interest of other actors, so that the issue of the link between climate change on the one hand and peace and security on the other ceases to be a peripheral matter, and all States see it as an issue for the Security Council. The aim is to ensure that activities related to maintaining international peace and security take account of climate change issues.

Has your experience as an elected member of the Security Council influenced the importance or interest that Niger attaches to IHL and humanitarian issues? Without asking you to indulge in crystal-ball-gazing, do you think that one can expect knowledge of IHL to have increased in Niger by the end of your mandate?

Serving on the Security Council for two years as an elected member has strengthened Niger's interest in IHL and humanitarian issues. Niger has also played a leadership role in promoting better consideration of current humanitarian issues. As previously noted, in 2020, Niger co-chaired the Informal Expert Group on Climate and Security of Members of the Security Council with Germany, which at that time was also an elected member of the Security Council. At the end of Germany's term of office, Niger continued to co-chair the Group with Ireland.

But Niger's interest in IHL and humanitarian issues is not new, and it will remain as strong as ever when our time on the Security Council comes to an end. Niger appreciates the importance of IHL and will continue not only to promote dissemination of the rules that this body of law sets out, but also to support humanitarian action for people in need.

Would you like to add anything for our readers?

Human suffering has no borders and no ideological affiliation. It challenges us all as human beings. The promotion of security and well-being must therefore remain one of the principal concerns of the international community. It should in no way be politicized.

Finally, I would like to pay a heartfelt tribute to the ICRC and to all humanitarian actors for the tremendous work they do every day to defend human dignity, nature and the values of humanity.

- 1See, for example, “Statement by the President of the Security Council”, UN Doc. S/PRST/2020/7, 28 July 2020, available at: https://undocs.org/en/S/PRST/2020/7 (all internet references were accessed in November 202).

- 2Kalla Ankourao, “Statement by the Minister for Foreign Affairs, Cooperation, African Integration and Nigeriens Abroad of the Niger”, UN Doc. S/00/99, 3 September 00, Annex 4, available at: https://undocs.org/S/00/99.

- 3See, for example, UNGA Res. 74/270, “Global Solidarity to Fight the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)”, April 2020, available at: https://undocs.org/en/A/RES/74/270; UNGA Res. 75/4, “Special Session of the General Assembly in Response to the Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Pandemic”, 9 November 2020, available at: https://undocs.org/en/A/RES/75/4; “Le coronavirus demeure toujours une menace à la paix et à la sécurité internationales”, ONU Info, 9 September 2020, available at: https://news.un.org/fr/story/2020/09/1076812.

- 4K. Ankourao, above note 2.

- 5ICRC, When Rain Turns to Dust: Understanding and Responding to the Combined Impact of Armed Conflicts and the Climate and Environment Crisis on People's Lives, Geneva, 2020, available at: https://shop.icrc.org/when-rain-turns-to-dust-pdf-en.

- 6Abdou Abarry, “Letter from the Permanent Representative of the Niger to the United Nations Addressed to the Secretary-General”, UN Doc. S/2020/882, 1 September 2020, available at: https://undocs.org/S/2020/882.

- 7K. Ankourao, above note 2.

- 8António Guterres, “Remarks to the Security Council High-level Open Debate on the Maintenance of International Peace and Security: Climate and Security”, 23 September 2021, available at: www.un.org/sg/en/node/25947.

- 9Brigi Rafini, “Statement by the Prime Minister of Niger, Brigi Rafini”, UN Doc. S/2021/18, 23 February 2021, Annex 8, available at: https://undocs.org/en/S/2021/18.

- 10“La Commission Climat Pour la Région du Sahel s'est dotée d'un plan d'investissement climat (PIC-RS 2018-2030) d'un coût global d'environ 440 milliards de dollars”, Tam Tam Info, 7 November 2020, available at: https://tinyurl.com/2s37wpnz.

- 11Ibid.

- 12B. Rafini, above note 9.