Note: A brief history of the International Review of the Red Cross

The International Review of the Red Cross1 has gone through many evolutions since it was first published in October 1869. All told, it has had sixteen editors-in-chief from diverse professional backgrounds,2 as well as many managing editors, thematic editors, editorial assistants and others, all working to support the production, promotion and distribution of the journal. It is now the oldest publication devoted to international humanitarian law (IHL), policy and action. Its collection represents a precious resource on the history of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) and the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement (the Movement), and on the development of humanitarian law and action at large. The Review continues to contribute significantly to these fields, so it is worthwhile to look back at the journal’s role in the past to see how it has evolved and reflect on where it is now, and where it may go in the future.

A bulletin connecting National Societies and tracing the evolution of humanitarian relief on the battlefield

The International Review of the Red Cross began its history as the Bulletin International des Sociétés de Secours aux Militaires Blessés, founded at the Second International Conference of the Red Cross and Red Crescent (International Conference), held in Berlin in 1869.3 The Conference felt it “indispensable” to set up a journal “to link the central committees [of what became the National Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies] of the various countries and bring to their attention the facts, official and otherwise, that are pertinent for them to know”.4

Originally under the editorial direction of Gustave Moynier, the Bulletin was a newsletter featuring updates from the National Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (National Societies), translated and published in French on a quarterly basis. The Bulletin thus created a link among the central committees of different relief societies that preceded the National Societies, and between those societies and the ICRC (at the time the Comité International de Secours aux Blessés, or Comité International, which became the ICRC in 1875). With national relief societies carrying out operations in the field and the ICRC at that time being a small committee of a few members who worked on a voluntary basis as a type of secretariat, the Bulletin served as an important channel for the exchange of updates on relief operations, new medical techniques and innovative ideas, and reviews of publications.5 Moreover, it acted as the “official general monitor” of the Red Cross.6

Thus, the Bulletin served as glue for the movement. Letters from leaders of relief societies show how important Bulletin content was to early national organizing efforts and many irritated notes complained to Gustave Moynier … when names or founding organizations were omitted from the record. … [T]he Bulletin was the movement’s “fountainhead” and source of information on common challenges. Gathering and publishing the medical field reports and letters of Red Cross personnel on the ground also allowed [International Committee] members to offer running commentary on actual experiences of medical provisioning, even in civil and colonial wars where the movement had no formal jurisdiction.7

The journal promoted new ideas in the field of humanitarian action: new medical inventions and innovations in the transportation of the wounded, but also legal developments and humanitarian best practices. It is worth noting that the legal articles and reviews of legal publications featured in the early years of the journal tied in with the growing importance of international law journals, a nascent trend.8

In her book about the history of the Red Cross, Caroline Moorehead notes:

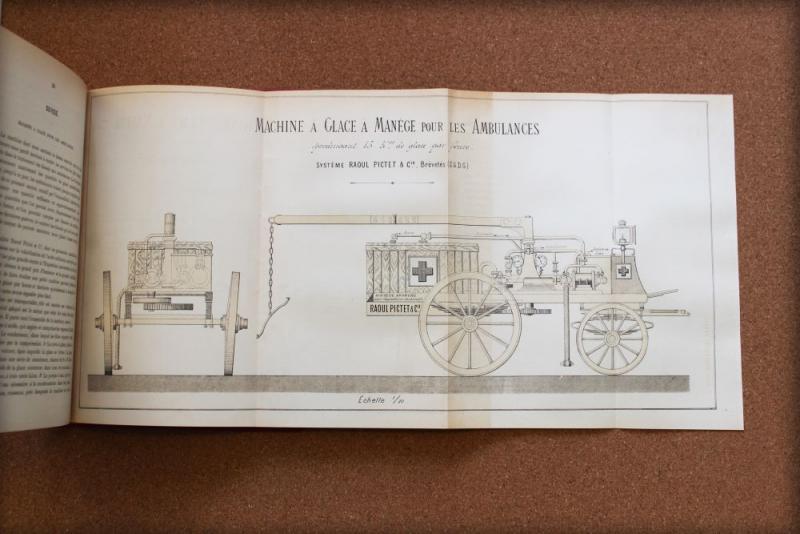

Imaginative, sometimes dotty, projects, with camels as stretcher bearers, or odd surgical instruments, filled the pages of a magazine, known as the Bulletin, launched in the late 1860s by the International Committee, and illustrated by charming black-and-white drawings. There was an ice-making machine, a device which claimed to turn salt water into fresh, and a portable kitchen which folded into a knapsack containing a spirit lamp, a rubber pipe for men too weak to drink from a cup, nails, rope, pots, towels, candles, rum and cognac, mustard powder, tea, salt, pepper and meat extract – the only trouble being that it was too heavy to carry more than a few paces.9

Typically, the Bulletin included communications which the International Committee or the central committees wished to bring to the attention of other members of the Movement and information on the activities of the various committees in times of peace or war, as well as bibliographical information, memoirs, speeches and letters on matters affecting the movement’s functions and progress, and all sorts of communications concerning the subject of its work.

The journal was also used as a strategic tool for the ICRC and its second president, Gustave Moynier, to circulate their ideas and guide the Movement.10 In a letter published in 1872, Moynier in fact proposed the establishment of an international criminal court.11 This proposal was revisited several times in the journal, with the Spanish national relief society responding in support and a second article from Moynier fleshing out the idea.12

Moynier being the main editor of the Bulletin for the first two years, and later a frequent contributor as president of the International Committee, the journal very much reflected his own personality, unfortunately including his racist and colonialist views.13 As for his well-known rivalry with Henry Dunant, this is revealed by the striking absence of any mention of the author of A Memory of Solferino during those years. The name of Dunant does not even appear on the advertisement for his book in the first issue of the Bulletin. As Moorehead remarks laconically: “The Red Cross was ever rivalrous.”14

The Bulletin International des Sociétés de Secours aux Militaires Blessés was, without fanfare, renamed the Bulletin International des Sociétés de la Croix-Rouge in 1886, finally incorporating “Red Cross” in its title. This followed a consultation in which National Societies gave their input on how to improve the journal, which likely led to the title change.15 This title change did not signal a shift in the focus of the journal, whose contents remained the same.

The First World War and the first major evolution in the editorial line

The First World War fundamentally transformed the scope, methods of work and geographical area of operations of the International Committee: from a small committee of volunteers based in Geneva, the ICRC quickly became an entity hiring staff, setting up and running the Agence Internationale des Prisonniers de Guerre (International Prisoners of War Agency), regularly conducting missions in war zones to visit the prisoner-of-war camps, and taking care of the repatriation of prisoners at the end of the conflict. During the same period, the organization established its first delegations abroad and expanded its operations to previously unfamiliar territories in Africa and Asia.16

This expansion in the activities and geographical reach of the ICRC was reflected in the Bulletin’s content. The Bulletin published regular reports on the conditions of detained prisoners of war17 in addition to the continuing reports from National Societies on their activities and, interestingly, even allegations by National Societies on State parties’ violations of IHL.18 The ICRC perhaps did not yet have enough experience of field operations to anticipate that publishing such denunciations could jeopardize its perception as a neutral humanitarian actor and be detrimental to its capacity to access detentions facilities or conflict zones and generally to operate in the midst of conflicts.19

The first part of the Bulletin had always been dedicated to the activities of the ICRC. In 1919, the Bulletin became a monthly publication and this first section became the Revue Internationale de la Croix-Rouge, as it became apparent that the ICRC required its own section to report on growing operations in the wake of its surge in activities during the First World War. The Revue and the Bulletin were published and distributed simultaneously.

The changes were presented in Volume 1 of the new combined publication, emphasizing that the role of the ICRC was to connect the National Societies so as to coordinate their operations.

In order to better carry out this task, [the Bulletin] has decided to give more publicity to reports of charitable activities. The trimestral Bulletin International, which for 49 years has published reports of the central committees of the Red Cross Societies, will become monthly, and next to the official portion where news of each Red Cross Society will continue to appear. … By enlarging its Bulletin and creating a Revue Internationale de la Croix-Rouge, the International Committee proposes to reinforce one of the few links that war has not broken and prepare the path for future International Red Cross Conferences that, in a future we hope is near, will once again reunite the representatives of all countries.20

In addition to its leading articles, the journal also reported on the activities of the ICRC and the National Societies, as well as the newly established League of Red Cross Societies (later to become known as the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies), which had its own regular section.

In the following years, the Revue continued to publish official declarations, communiqués, reports and commentaries, as well as studies attesting to the Movement’s activities in various theatres of operations, sharing to a certain extent the experience of ICRC delegates as they distributed aid, repatriated the wounded and sick, organized exchanges of prisoners and searched for missing persons.21

“The Great War is over!”: A period of anticipation

In the January 1919 edition of the journal, the ICRC announced in the Bulletin portion of the journal: “Elle est finie, la grande guerre!” (“The Great War is over!”)22 Although it was clear that many challenges lay ahead, the International Committee had come out of the war strong, prestigious and internationally respected.23

In 1919, the League of Red Cross Societies was created. Although, as Paul Des Gouttes was keen to point out,24 some form of federation of Red Cross Societies had long been discussed, the creation of the League was perceived as an attempt to replace the International Committee, and the early days of the latter’s relations with the new international organ of the Red Cross were tumultuous. The ICRC felt the need to continuously remind its readers that the journal was “Published by the International Committee, founder of this institution [the Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement]” on the cover of 415 editions of the standalone Bulletin and its continuation as a section in the Revue between 1902 and 1947. Eventually the complementarity of the ICRC and the League was officially recognized when the Statutes of the International Red Cross were adopted at the 13th International Conference in 1928.25

By the 1930s, it had become clear that the world was once again “drifting towards war” on a global scale.26 While the International Committee could do very little to prevent this, given its principles, its members seemed to be preparing themselves for what was to come. The Revue (and later the Review) was a reflection of this time. As Caroline Moorehead puts it:

[I]n the pages of the Review, which, month by month continued to monitor the activities and interests of the Red Cross world – which made it such an excellent monitor of the times – the talk was all of readiness. Read carefully, however, the Review could also be seen as a warning of things to come.27

The Revue continued to publish on the activities of National Societies, but, as Moorhead also remarks:

The tone of the Review itself, however, was altering; gone were the ebullient, self-congratulatory reports of post-war years; in their place had come bald, tight-lipped warnings – about chemical warfare, about uncontrollable new weapons, about the need to protect civilians – that seemed to grow more urgent year by year.28

The Second World War and its aftermath

During the Second World War, the Revue continued to publish on Red Cross activities, relief work, missions by delegates, violations of the Conventions, international gatherings, conditions in which prisoners of war were kept, new medical and military developments, and newcomers to the Red Cross world.29 What is conspicuously lacking, however, is almost any mention of the concentration camps and atrocities being committed by the Nazis. Until the autumn of 1944, there was no discussion of them in the Revue, although they were actively examined by the International Committee.

In 1949, decades-long efforts to ensconce protections for civilians in IHL culminated in four Geneva Conventions with updated provisions providing protection for sick and wounded soldiers on land and at sea, for prisoners of war, and for civilians in the hands of the enemy.30 The revolutionary Article 3 common to the Geneva Conventions extended their scope to include non- international armed conflict.31 The Revue reflected this evolution by publishing invaluable resources on the process: programmes, minutes of expert meetings and the Diplomatic Conference, speeches, resolutions, etc. Throughout the development, interpretation and implementation of IHL, “at each successive stage, the Revue has kept a record of developments in the law, while at the same time helping to clarify, explain and spread knowledge of its provisions”.32

In the aftermath of the Second World War, the Revue began giving priority to the operational activities of the ICRC and its delegates, and in 1948 it introduced an English-language supplement to the original French version, reproducing a selection of the contents of each monthly issue in English. Spanish and German supplements were also introduced in 1949 and 1950 respectively.

In April 1961, the International Review of the Red Cross was born as a separate, fully-fledged English-language publication, and from July of that year the journal was published in French and English editions.

In addition to legal developments, the journal continued to feature ICRC operations. On a number of occasions, the Review published periodic overviews of ICRC operations in protracted conflicts – for example, in relation to Nigeria and Biafra between 1967 and 1970, in relation to which the Review published an overview of the organization’s work in a monthly column.33 As a result, the Review was home to discussions on the nature of humanitarian action, the risks of politicization of aid and the way in which the ICRC needed to adapt while remaining true to its basic mission.34 From the late 1960s onwards, however, coverage of ICRC operations was gradually reduced in favour of more IHL- related content.35

As the then editor-in-chief Jacques Meurant states, the reasons for this were twofold:

[I]n the first place, theatres of operations were becoming too numerous to be reported on comprehensively in time to remain of topical interest to the reader; secondly from 1977 on the Review, previously a monthly [publication], appeared every two months. Other periodicals [took] over this task, and the Annual Report gives a detailed account of ICRC’s activities.36

In 1969 the journal celebrated its 100th anniversary with a commemorative edition. In it, one author remarked that the Review:

has not sought to be popular, but to remain what its founders wished it to be: the faithful and objective witness to the work of the Red Cross in Geneva and in the world, the reflection of the moral principles of the Red Cross and the elaboration of its doctrine, an echo of the constructive effort at all latitudes, in all civilizations, to defend man and his dignity.37

1969 marked the start of a new era for IHL as disturbing trends such as indiscriminate bombing and new weapons technology led to the re-examination of so-called “Hague law” governing the conduct of hostilities and the ICRC pushed for more access in non-international armed conflicts.38

The adoption of the 1977 Additional Protocols additional to the Geneva Conventions, based on drafts prepared by the ICRC, was a significant milestone in the development of the law after nearly ten years of negotiations.39 During the negotiations of these two important texts, “the Review not only provided detailed accounts of the preparatory meetings and the sessions of the Diplomatic Conferences … but also endeavoured to make a contribution by publishing pertinent studies, especially on new or sensitive issues”.40

A powerful channel for dissemination of humanitarian law and principles

In the years that followed, the Review also took part in the campaign to persuade States to adopt and ratify the Additional Protocols.41 It continued to be used as a tool of influence and persuasion in the ICRC’s promotion of IHL, by clarifying how the law should be interpreted42 and providing guidance for those who would conduct their own IHL trainings.43

In 1978 the Review started to be published every two months, and photographs and images were no longer printed in the journal for a time. The Review became a quarterly publication in 1998. It also extended its readership by adding Arabic- (1988), Russian- (1994) and Chinese-language editions (1997) to the existing versions in French, English, German and Spanish.

In the 1990s, reports of the Movement’s “external activities” and “news from headquarters” began to fade and the Review developed a predominantly legal – and more academic – focus under the editorial direction of Jacques Meurant and Hans-Peter Gasser. This is perhaps most notable beginning in 1997, with the January/February edition devoted to commentary and discussions on the International Court of Justice’s Nuclear Weapons Advisory Opinion.44 The Review subsequently embraced a thematic approach during Toni Pfanner’s time as editor-in-chief, and this approach continues to be reflected in the journal to date. The Review has also moved from a focus on explanation and awareness-raising of the law to generating legal and policy debate in view of current challenges and controversies, following growing interest in humanitarian policy and action among academia but also government and military experts, as well as the expansion of humanitarian action, the development of international criminal justice in the 1990s, and the repercussions of the so-called “war on terror” in the 2000s, among other developments.

From March 1999 to December 2004, the journal was briefly co-published in French and English, with content being made available in one language with a summary in the other. Starting in 2005, the Review’s primary language of publication has been English. A “French Selection” of articles has been published on a yearly basis between 2005 and 2010, and on a more regular, thematic basis beginning in 2011.

As of 2006, the Review is produced by the ICRC and published by Cambridge University Press. The move to a partnership with an established academic publisher and the introduction of an Editorial Board in 2004, signifying a shift towards academic independence, are indicative of the evolution of the Review into a more academic publication which no longer acts as a mouthpiece for the ICRC but instead acts as a platform for debate. This reflects the growing expertise in humanitarian law, policy and action outside the Movement, which is better influenced through engaging in discussion and debate than through repetition of the law and institutional positions. The journal received its first Journal Impact Factor in 2011 and instituted a formal double-blind peer review process in 2012 to guarantee the high academic quality of contributions.

The Review today

The Review’s current aim is to stimulate research and discussion related to humanitarian law, policy and practice. Via a thematic approach, the journal publishes multidisciplinary content related to the subject of each issue. The content is varied, including interviews and testimonies, articles, opinion notes, debate sections, in folios, book reviews and reports/documents. Another innovation in the editorial line has included the voices of those affected by armed conflict, left for too long on the fringes of humanitarian reflection.45 The majority of contributions focus on recent developments in humanitarian law and policy, while others aim at providing the historical, sociological, political, economic or other analysis that complements the legal and policy debate. Starting in 2016 the Review has been published three times per year.

Today the journal aims to maintain the rigorous, academic nature of its content while at the same time hosting new perspectives in order to focus the discussion on various fault lines and key contemporary issues in IHL and humanitarian action. In terms of gender parity, in its issues published between 2015 and 2018, the Review’s authorship was 58% male and 42% female. Authors during that period came from a range of professional backgrounds, including academics, researchers, humanitarian practitioners, legal professionals and military personnel, but the largest source of contributors continues to be the ICRC. In terms of geographic diversity of authorship, Review authors in these three years came from thirty-six States, mainly in Western European and North America. The journal is engaging in efforts to solicit and publish submissions from Latin America, Africa and Asia, including calls for papers to be translated by colleagues who work on the language selections of the journal.

The journal is distributed widely. In addition to some 8,718 subscriptions via Cambridge University Press, the Review is distributed free of charge by the ICRC worldwide. In the initial distribution of each new issue, approximately 1,900 copies are distributed by ICRC delegations in the field.

It is interesting to note which editions are most frequently consulted online. The top three issues of the Review accessed on the ICRC’s website in English (based on clicks and downloads) are “Scope of the Law in Armed Conflict” (2014), “New Technologies and Warfare” (2012) and “Sexual Violence in Armed Conflict” (2014). Across all of the language selections, the most popular issues have been those with a focus on IHL along with those focused on gender and technology-related issues.46

As the Review commemorates its 150th anniversary, the ICRC is making the entirety of its archives available to the public free of charge via icrc.org. The hope is that this will encourage researchers to use this wealth of documentation to rediscover ideas, identify trends and inform future discussions and debates.47

In honour of this momentous anniversary, it is important not only to remember the past and take stock of the present, but also to look to the future. The journal has kept pace with the times over the past century and a half, and it will continue to do so moving forward. Its evolution is a reflection of that of the humanitarian sector and the larger international community, adapting and changing to each new era in international relations to promote respect for the law and the creation of an environment conducive to respect for human dignity in armed conflict and other situations of violence. That this will happen is certain. How it will happen remains to be seen.

Annex 1

Publication of an International Bulletin48

The creation of an International Bulletin, consecrated to the movement for the relief of wounded soldiers, after having been proposed in Paris in 1867, studied by the International Committee in its Memorandum of 20 June 1868, was resolved by the Berlin Conference on 27 April 1869 in the following terms:

The Conference sees the creation of a journal as indispensable, to link the central committees of the various countries and bring to their attention the facts, official and otherwise, that are pertinent for them to know.

The editing of this journal is entrusted to the International Committee of Geneva, without any costs being incurred on these grounds at the expense of the members of the Committee.

The bulletins that it will publish will be periodical in nature, at a frequency determined by the members of the Committee.

One part of the publication may be reserved for announcements, reviews of significant works, and descriptions of devices or inventions relevant to the relief of wounded or sick soldiers.

Endowed with the confidence of the central committees, the International Committee considers itself lucky to be able to undertake useful work, in this way, toward the advancement of an institution to which it has pledged its full support. It is also pleased that its new functions will allow it to support the movement with the central committees.

It is these last, in fact, in the thinking of the Berlin Conference, who should provide the materials for the planned Bulletin. It was understood that the collection would serve as the voice of the central committees, to inform one another of all that could be of interest to them, and that they alone would have the right to include articles, which would enhance the value of the Bulletin in giving it an official character, of a sort. The International Committee will gather, coordinate and publish these documents, completing them as needed with specific information.

The result of this combination is that each central committee must make itself available to work on the Bulletin, by giving it complete information related to its own country. The elements of a substantial publication will certainly not be lacking, but only on the condition that those concerned take care to provide them. Additionally, the International Committee hopes that the central committees, inspired by this truth, will do all that is in their power to help, with their advice as well as their cooperation, so that the collective Bulletin may be worthy of the movement as it excels at the service to which it is destined.

The framework of the Bulletin will encompass not only the work of the central committees and the relief societies, their staff and their organization, but also facts surrounding the official health services, or charitable associations whose efforts work toward the same goal, new publications (books, brochures, journal articles), inventions for the amelioration of the fate of the wounded, etc., etc.

The central committees may also use the Bulletin to communicate their ideas to each other, ask each other questions, and search for solutions to problems that preoccupy them.

Each committee will take responsibility for the communications it publishes. The contents may be divided into as many distinct articles as needed.

The preceding lines are the core of the International Committee’s 15 June 1869 circular addressed to the central committees of the various countries. We need not enter into further detail about the nature of the Bulletin that we undertake to publish today, which will contain the general archives of the movement, starting with the Berlin Conference.

- 1This note was drafted by the Review editorial team. Special thanks to Ellen Policinski, Kvitoslava Krotiuk, Cedric Cotter, Eline Goovaerts and Safi van’t Land.

- 2See the photo gallery, “The Editors-in-Chief of the Review, 1869–2019”, in this issue of the Review.

- 3“Publication d’un bulletin international”, Bulletin International des Sociétés de Secours aux Militaires Blessés, Vol. 1, No. 1, 1869.

- 4Ibid. See English translation in Annex 1 of this article. For further discussion on the foundation and evolution of the journal, see, e.g., Jean-Georges Lossier, “Comment naquit le ‘Bulletin international’”, Revue Internationale de la Croix-Rouge, Vol. 51, No. 610, 1969; Victor Segesvary, “Cinquante années de la ‘Revue’”, Revue Internationale de la Croix-Rouge, Vol. 51, No. 610, 1969; and the article by Daniel Palmieri in this issue of the Review.

- 5See Jacques Meurant, “The 125th Anniversary of the International Review of the Red Cross: A Faithful Record. Part III: The International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement: Solidarity and Unity”, International Review of the Red Cross, Vol. 35, No. 307, 1995.

- 6Gustave Moynier, “Les dix premières années de la Croix-Rouge: III. Sociétés de secours”, Bulletin International des Sociétés de Secours aux Militaires Blessés, Vol. 4, No. 16, 1873, p. 195.

- 7Jean H. Quataert, “A New Look at International Law: Gendering the Practices of Humanitarian Medicine in Europe’s ‘Small Wars’, 1879–1907”, Human Rights Quarterly, Vol. 40, No. 3, 2018, p. 560.

- 8See Ignacio de la Rasilla, “A Very Short History of International Law Journals (1869–2018)”, European Journal of International Law, Vol. 29, No. 1, 2018.

- 9Caroline Moorehead, Dunant’s Dream: War, Switzerland and the History of the Red Cross, Carroll & Graf, New York, 1999, p. 57. See also “Machine à glace pour les ambulances”, Bulletin International des Sociétés de Secours aux Militaires Blessés, Vol. 10, No. 37, 1879, p. 30; “Batterie de cuisine portative du colonel baron van Tuyll van Serooskerken”, Bulletin International de Secours aux Militaires Blessés, Vol. 1, No. 2, 1870, p. 94.

- 10See the articles by David Forsythe and Daniel Palmieri in this issue of the Review.

- 11Gustave Moynier, “Note sur la création d’une institution judiciaire internationale propre a prévenir et a réprimer les infractions à la Convention de Genève”, Bulletin International des Sociétés de Secours aux Militaires Blesses, Vol. 3, No. 11, 1872, p. 122.

- 12“Institution judiciaire internationale”, Bulletin International des Sociétés de Secours aux Militaires Blessés, Vol. 3, No. 12, 1872, p. 203; G. Moynier, above note 11.

- 13“La Croix-Rouge chez les nègres”, Bulletin International des Sociétés de Secours aux Militaires Blessés, Vol. 11, No. 41, 1880.

- 14C. Moorehead, above note 9, p. 57.

- 15See Bulletin International des Sociétés de Secours aux Militaires Blessés, Vol. 16, No. 62, 1885, p. 53. In this issue there is a discussion about an “enquête sur le role du Comité international et les relations des comités centraux”, and National Societies are asked for their input on how to improve the journal. The first issue of 1886 does not explain the name change.

- 16For more on the ICRC’s evolution during and after the First World War, see Daniel Palmieri, “An Institution Standing the Test of Time? A Review of 150 Years of the History of the International Committee of the Red Cross”, International Review of the Red Cross, Vol. 94, No. 888, 2012; André Durand, History of the International Committee of the Red Cross: From Sarajevo to Hiroshima, Henry Dunant Institute, Geneva, 1984; Cédric Cotter, (S’)Aider pour survivre: Action humanitaire et neutralité suisse pendant la Première Guerre mondiale, Georg Editeur, Geneva, 2017.

- 17See, for example, the periodic articles published by the Agence Internationale des Prisonniers de Guerre, including “La situation des prisonniers de guerre et des internes civils depuis la conclusion des armistices”, Revue Internationale de la Croix-Rouge, Vol. 1, No. 1, 1919. And see “Prisonniers russes”, Revue Internationale de la Croix-Rouge, Vol. 1, No. 5, 1919; “Prisonniers de guerre hongrois en Roumanie”, Revue Internationale de la Croix-Rouge, Vol. 1, No. 9, 1919.

- 18See, for example, “La Croix-Rouge russe a communiqué deux mémoires tendant a établir des cas de violation de la Convention de Genève par les armées allemandes et austro-hongroises”, Bulletin International des Sociétés de la Croix-Rouge, Vol. 47, No. 187, 1916, pp. 355–356; and the “Protestations” in e.g. Bulletin International des Sociétés de la Croix-Rouge, Vol. 48, No. 189, 1917, pp. 15–35 (France against Bulgaria, Bulgaria against France and Great Britain, and Russia against Turkey), or Vol. 48, No. 191, 1917, pp. 384–397 (Great Britain and France against Germany, Bulgaria against France and Great Britain, Turkey against Russia).

- 19To read more, see Lindsey Cameron, “The ICRC in the First World War: Unwavering Belief in the Power of Law?”, International Review of the Red Cross, Vol. 97, No. 900, 2015.

- 20Paul des Gouttes, Etienne Clouzot and K. de Watteville, “Revue Internationale de la Croix-Rouge et Bulletin International des Societés de la Croix-Rouge”, Revue Internationale de la Croix-Rouge, Vol. 1, No. 1, 1919, p. 2.

- 21See Jacques Meurant, “The 125th Anniversary of the International Review of the Red Cross: A Faithful Record. Part I: Protection and Assistance”, International Review of the Red Cross, Vol. 34, No. 303, 1994, pp. 533–534.

- 22“Comité International”, Revue Internationale de la Croix-Rouge, Vol. 1, No. 1, 1919, p. 69. See also C. Moorehead, above note 9, p. 256.

- 23C. Moorehead, above note 9, p. 257.

- 24Paul Des Gouttes, “De la Fédération des Sociétés de la Croix-Rouge”, Revue Internationale de la Croix- Rouge, Vol. 1, No. 8, 1919.

- 25See Colonel Draudt and Max Huber, “Rapport à la XIIIme Conférence international de la Croix-Rouge sur les status de la Croix-Rouge internationale”, Revue Internationale de la Croix-Rouge, Vol. 10, No. 119, 1928; J. Meurant, above note 5, pp. 463–465.

- 26C. Moorehead, above note 9, p. 299.

- 27Ibid.

- 28Ibid., p. 300.

- 29Ibid., p. 411.

- 30Jean S. Pictet, “Les nouvelles Conventions de Genève et la Croix-Rouge”, Revue Internationale de la Croix- Rouge, Vol. 31, No. 369, 1949; “Conventions de Genève pour la protection des victimes de la guerre: Convention de Genève relative à la protection des personnes civiles en temps de guerre, du 12 août 1949”, Revue Internationale de la Croix-Rouge, Vol. 31, No. 386, 1949; “Observations générales sur l’élaboration de la Convention relative à la protection des civils, à la Conférence diplomatique de Genève”, Revue Internationale de la Croix-Rouge, Vol. 31, No. 386, 1949.

- 31“Séance de Clôture. Discours de M. Max Petitpierre, vice-président du Conseil Fédéral suisse, président de la Conférence Diplomatique de Genève”, Revue Internationale de la Croix-Rouge, Vol. 31, No. 386, 1949, p. 552. See also Catherine Rey-Schyrr, “The Geneva Conventions of 1949: A Decisive Breakthrough. Part I”, International Review of the Red Cross, Vol. 81, No. 834, 1999; Catherine Rey-Schyrr, “The Geneva Conventions of 1949: A Decisive Breakthrough. Part II”, International Review of the Red Cross, Vol. 81, No. 835, 1999.

- 32Jacques Meurant, “The 125th Anniversary of the International Review of the Red Cross: A Faithful Record. Part II: Victories of the Law”, International Review of the Red Cross, Vol. 35, No. 306, 1995, p. 286.

- 33Jacques Freymond, “Aid to the Victims of the Civil War in Nigeria”, International Review of the Red Cross, Vol. 10, No. 107, 1970; J. Meurant, above note 21, p. 535. See also “Help to War Victims in Nigeria”, International Review of the Red Cross, Vol. 8, No. 92, 1968.

- 34See, e.g., Walter Bargatzsky, “Red Cross Unity in the World”, International Review of the Red Cross, Vol. 14, No. 163, 1974; Jacques Freymond, “The International Committee of the Red Cross within the International System”, International Review of the Red Cross, Vol. 12, No. 134, 1972; “Under the Presidency of Mr. Alexander Hay, the ICRC from 1976 to 1987: Controlled Expansion”, International Review of the Red Cross, Vol. 27, No. 261, 1987. See also J. Meurant, above note 21, pp. 534–535.

- 35Throughout the 1970s, in particular, there was a gradual increase in focus on dissemination articles (for example, the Jean Pictet Commentaries published in 1979–1980) and “Geneva news”, so the coverage of specific operations, though still present, was comparatively reduced.

- 36See J. Meurant, above note 21, p. 538, fn. 9.

- 37J.-G. Lossier, above note 4.

- 38J. Meurant, above note 32, pp. 285 ff; Cornelio Sommaruga, “The Protocols Additional to the Geneva Conventions: A Quest for Universality”, International Review of the Red Cross, Vol. 27, No. 258, 1987.

- 39François Bugnion, “Adoption of the Additional Protocols of 8 June 1977: A Milestone in the Development of International Humanitarian Law”, International Review of the Red Cross, Vol. 99, No. 905, 2017. See also the Protocols Additional to the Geneva Conventions, resolutions of the Diplomatic Conference and extracts from the final act of the Diplomatic Conference, International Review of the Red Cross, Vol. 17, No. 197–198, 1977.

- 40J. Meurant, above note 32, p. 288, citing, e.g., Claude Pilloud, “The Concept of International Armed Conflict: Further Outlook”, International Review of the Red Cross, Vol. 15, No. 166, 1975.

- 41Hans-Peter Gasser, “Steps Taken to Encourage States to Accept the 1977 Protocols”, International Review of the Red Cross, Vol. 27, No. 258, 1987.

- 42See, e.g., “Fundamental Rules of Humanitarian Law Applicable in Conflicts”, International Review of the Red Cross, Vol. 18, No. 206, 1978; Stanislaw Nahlik, “A Brief Outline of International Humanitarian Law”, International Review of the Red Cross, Vol. 24, No. 241, 1984; “Technical Note on the Protocols of 8 June 1977 Additional to the Geneva Conventions”, International Review of the Red Cross, Vol. 24, No. 242, 1984. See also J. Meurant, above note 32.

- 43See, e.g., René Kosirnik, “Dissemination of International Humanitarian Law and of the Principles and Ideals of the Red Cross and Red Crescent”, International Review of the Red Cross, Vol. 32, No. 287, 1992; “Guidelines for the 90s”, International Review of the Red Cross, Vol. 32, No. 287, 1992. See also J. Meurant, above note 32.

- 44International Review of the Red Cross, Vol. 37, No. 316, 1997.

- 45For more on how civilians as beneficiaries of humanitarian action have been represented in the journal, see the article by Ben Holmes in this issue of the Review.

- 46As of November 2018. Top issues determined based on clicks and downloads.

- 47For more information, see Vincent Bernard’s editorial in this issue of the Review.

- 48First published as “Publication d’un bulletin international”, Bulletin International des Sociétés de Secours aux Militaires Blessés, Vol. 1, No. 1, 1869.