AI for humanitarian action: Human rights and ethics

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic currently roiling around the globe has been devastating on many fronts. As the United Nations (UN) Secretary-General recently noted, however, the pandemic has also been a learning opportunity about the future of global crisis response. Specifically, the world is “witnessing first-hand how digital technologies help to confront the threat and keep people connected”.1 Artificial intelligence (AI) is at the forefront of many of these data-driven interventions. In recent months, governments and international organizations have leveraged the predictive power, adaptability and scalability of AI systems to create predictive models of the virus's spread and even facilitate molecular-level research.2 From contact tracing and other forms of pandemic surveillance to clinical and molecular research, AI and other data-driven interventions have proven key to stemming the spread of the disease, advancing urgent medical research and keeping the global public informed.

The purpose of this paper is to explore how a governance framework that draws from human rights and incorporates ethics can ensure that AI is used for humanitarian, development and peace operations without infringing on human rights. The paper focuses on the use of AI to benefit the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and other humanitarian purposes. Accordingly, it will focus on risks and harms that may arise inadvertently or unavoidably from uses that are intended to serve a legitimate purpose, rather than from malicious uses of AI (of which there could be many).

As the Secretary-General has noted, AI is already “ubiquitous in its applications”3 and the current global spotlight is likely to expedite its adoption even further.4 As the COVID crisis has laid bare, AI will increasingly shape the global response to the world's toughest problems, especially in the fields of development and humanitarian aid. However, the proliferation of AI, if left unchecked, also carries with it serious risks to human rights. These risks are complex, multi-layered and highly context-specific. Across sectors and geographies, however, a few stand out.

For one, these systems can be extremely powerful, generating analytical and predictive insights that increasingly outstrip human capabilities. They are therefore liable to be used as replacements for human decision-making, especially when analysis needs to be done rapidly or at scale, with human overseers often overlooking their risks and the potential for serious harms to individuals or groups of individuals that are already vulnerable.5 Artificial intelligence also creates challenges for transparency and oversight, since designers and implementers are often unable to “peer into” AI systems and understand how and why a decision was made. This so-called “black box” problem can preclude effective accountability in cases where these systems cause harm, such as when an AI system makes or supports a decision that has a discriminatory impact.6

Some of the risks and harms implicated by AI are addressed by other fields and bodies of law, such as data privacy and protection,7 but many appear to be entirely new. AI ethics, or AI governance, is an emerging field that seeks to address the novel risks posed by these systems. To date, it is dominated by the proliferation of AI “codes of ethics” that seek to guide the design and deployment of AI systems. Over the past few years, dozens of organizations – including international organizations, national governments, private corporations and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) – have published their own sets of principles that they believe should guide the responsible use of AI, either within their respective organizations or beyond them.8

While these efforts are often admirable, codes of ethics are limited in key respects: they lack a universally agreed framework; they are not binding, like law, and hence do not promulgate compliance; they often reflect the values of the organization that created them, rather than the diversity of those potentially impacted by AI systems; and they are not automatically operationalized by those designing and applying AI tools on a daily basis. In addition, the drafters of these principles often provide little guidance on how to resolve conflicts or tensions between them (such as when heeding one principle would undermine another), making them even more difficult to operationalize. Moreover, because tech companies create or control most AI-powered products, this governance model relies largely on corporate self-regulation – a worrying prospect given the absence of democratic representation and accountability in corporate decision-making.

Applying and operationalizing these principles to development and humanitarian aid poses an additional set of challenges. With the exception of several recent high-quality white papers on AI ethics and humanitarianism, guidance for practitioners in this rapidly evolving landscape remains scant.9 This is despite the existence of several factors inherent in development or humanitarian projects that either exacerbate traditional AI ethics challenges or implicate entirely new ones.

AI governance is quickly emerging as a global priority. As the Secretary-General's Roadmap for Digital Cooperation states clearly and repeatedly, the global approach to AI – during COVID and beyond – must be in full alignment with human rights.10 The UN and other international organizations have devoted increasing attention to this area, reflecting both the increasing demand for AI and other data-driven solutions to global challenges – including the SDGs – and the ethical risks that these solutions entail. In 2019, both the UN General Assembly11 and UN Human Rights Council (HRC)12 passed resolutions calling for the application of international human rights law to AI and other emerging digital technologies, with the General Assembly warning that “profiling, automated decision-making and machine-learning technologies, … without proper safeguards, may lead to decisions that have the potential to affect the enjoyment of human rights”.13

There is an urgency to these efforts: while we wrangle with how to apply human rights principles and mechanisms to AI, digital technologies continue to evolve rapidly. The international public sector is deploying AI more and more frequently, which means new risks are constantly emerging in this field. The COVID-19 pandemic is a timely reminder. To ensure that AI tools enable human progress and contribute to achieving the SDGs, there is a need to be proactive and inclusive in developing tools, policies and accountability mechanisms that protect human rights.

The conclusions contained herein are based on qualitative data emerging from multi-stakeholder consultations held or co-hosted by UN Global Pulse along with other institutions responsible for protecting privacy and other human rights, including the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (UN Human Rights) and national data protection authorities;14 multiple interviews and meetings with the diverse panel of AI and data experts that comprise Global Pulse's Expert Group on Governance of Data and AI;15 guidance and reporting from UN human rights experts; scholarly work on human rights and ethics; and practical guidance for the development and humanitarian sectors issued by organizations like the World Health Organization, the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA),16 the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC),17 the Harvard Humanitarian Initiative18 , Access Now,19 Article 19,20 USAID's Center for Digital Development,21 and the Humanitarian Data Science and Ethics Group (DSEG).22

AI in humanitarian aid: Opportunities

Artificial intelligence is not a specific technology. Rather, it is a broad term encompassing a set of tools or capabilities that seek to emulate aspects of human intelligence. As a category, AI generally refers to a system that automates an analytical process, such as the identification and classification of data; in rarer cases, an AI system may even automate a decision. Hence, some prefer the term “automated intelligent system” rather than the more commonly used “artificial intelligence” or “AI”. For the purposes of this paper, “AI” will refer primarily to machine learning (ML) algorithms, which are a common component of AI systems defined by the ability to detect patterns, learn from those patterns, and apply those learnings to new situations.23 ML models may be either supervised, meaning that they require humans to feed them a set of rules to apply, or unsupervised, meaning that the model is capable of learning rules from the data itself and therefore does not require human coders to feed in rules. For this reason, this latter set of models is often described as self-teaching.24 Deep learning (DL) is, in turn, a more potent subset of ML that uses layers of artificial neural networks (which are modelled after neurons in the human brain) to detect patterns and make predictions.25

Algorithmic systems are capable of “execut[ing] complex tasks beyond human capability and speed, self-learn[ing] to improve performance, and conduct[ing] sophisticated analysis to predict likely future outcomes”.26 Today, these systems have numerous capabilities that include natural language processing, computer vision, speech and audio processing, predictive analytics and advanced robotics.27 These and other techniques are already being deployed to augment development and humanitarian action in innovative ways. Computer vision is being used to automatically identify structures in satellite imagery, enabling the rapid tracking of migration flows and facilitating the efficient distribution of aid in humanitarian crises.28 Numerous initiatives across the developing world are using AI to provide predictive insights to farmers, enabling them to mitigate the hazards of drought and other adverse weather, and maximize crop yields by sowing seeds at the optimal moment.29 Pioneering AI tools enable remote diagnosis of medical conditions like malnutrition in regions where medical resources are scarce.30 The list grows longer every day.31

Several factors explain the proliferation of AI in these and other sectors. Perhaps the most important catalyst, however, is the data revolution that has seen the exponential growth of data sets relevant to development and humanitarianism.32 Data are essential fuel for AI development; without training on relevant data sets, an AI model cannot learn. Finding quality data has traditionally been more difficult in developing economies, particularly in least developed countries33 and in humanitarian contexts, where technological infrastructure, resources and expertise are often rudimentary. According to a recent comprehensive white paper from the DSEG, however, this has begun to change:

Currently, we are witnessing unprecedented rates of data being collected worldwide, a wider pool of stakeholders producing “humanitarian” data, data becoming more machine readable, and data being more accessible via online portals. This has enabled an environment for innovation and progress in the sector, and has led to enhanced transparency, informed decision making, and effective humanitarian service delivery.34

Key challenges for rights-respecting AI

The very characteristics that make AI systems so powerful also pose risks for the rights and freedoms of those impacted by their use. This is often the case with emerging digital technologies, however, so it is important to be precise about what exactly it is about AI that is “new” or unique – and therefore why it requires particular attention A thorough technical analysis of AI's novel characteristics is beyond the scope of this paper, but some of the most frequently cited challenges of AI systems in the human rights conversation are summarized in the following paragraphs.

Lack of transparency and explainability

AI systems are often obscure to human decision-makers; this is also known as the black box problem.35 Unlike traditional algorithms, the decisions made by ML or DL processes can be impossible for humans to trace, and therefore to audit or otherwise explain to the public and to those responsible for monitoring their use (this also known as the principle of explainability).36 This means that AI systems can also be obscure to those impacted by their use, leading to challenges for ensuring accountability when systems cause harm. The obscurity of AI systems can preclude individuals from recognizing if and why their rights were violated and therefore from seeking redress for those violations. Moreover, even when understanding the system is possible, it may require a high degree of technical expertise that ordinary people do not possess.37 This can frustrate efforts to pursue remedies for harms caused by AI systems.

Accountability

This lack of transparency and explainability can severely impede effective accountability for harms caused by automated decisions, both on a governance and an operational level. The problem is twofold. First, individuals are often unaware of when and how AI is being used to determine their rights.38 As the former UN Special Rapporteur on the Promotion and Protection of Freedom of Opinion and Expression David Kaye has warned, individuals are unlikely to be aware of the “scope, extent or even existence of the algorithmic decision-making processes that may have an impact on their enjoyment of rights”. Individual notice about the use of AI systems is therefore “almost inherently unavailable”.39 This is especially true in humanitarian contexts, where impacted individuals are often not able to give meaningful consent to data collection and analysis (e.g., because it is required to receive essential services).40

Second, the obscurity of the data economy and its lack of accountability for human rights41 can make it difficult for individuals to learn of harms to their rights and to seek redress when those harms occur. It can also make it difficult even for knowledgeable experts or fact-finders to audit these systems and diagnose faults. The organizational complexity of most development and humanitarian projects can compound these challenges.42 When a single project comprises a long chain of actors (including funders, foreign governments, international organizations, contractors, private sector vendors, local government entities, civil society partners and data collectors), who is ultimately responsible when a system spits out a discriminatory decision (or analysis that ultimately sways said decision)?

Unpredictability

A hallmark of ML and DL algorithms is their ability to learn and evolve in unpredictable ways. Put another way, they are able to “progressively identify new problems and develop new answers. Depending on the level of supervision, systems may identify patterns and develop conclusions unforeseen by the humans who programmed or tasked them.”43 Therein lies their essential value; ML algorithms can, in some cases, analyze data that they have not necessarily been trained to analyze, enabling them to tackle new tasks or even operate in new contexts. At the same time, however, a system's functional solutions will not always be logical or even understandable to human interpreters. This characteristic makes it difficult for human designers and implementers to predict – let alone explain – the nature and level of risk posed by a system or its application in a specific context. Moreover, there is a limit to the adaptability of even the most potent ML systems. Many do not generalize well to new contexts, resulting in extreme unpredictability when deployed on data that differs significantly from their training data.

Erosion of privacy

The ability of AI systems to analyze and draw inferences from massive quantities of private or publicly available data can have serious implications for many protected facets of the right to privacy. AI systems can reveal sensitive insights into individuals’ whereabouts, social networks, political affiliations, sexual preferences and more, all based on data that people voluntarily post online (such as the text and photos that users post to social media) or incidentally produce from their digital devices (such as GPS or cell-site location data).44 These risks are especially acute in humanitarian contexts, where those impacted by an AI system are likely to be among the most marginalized. As a result, data or analysis that would not ordinarily be considered sensitive might become sensitive. For instance, basic identifying information – such as names, home towns and addresses – may be publicly available information in most contexts, but for a refugee fleeing oppression or persecution in their home country, this information could jeopardize their safety and security if it were to end up in the wrong hands.45 In addition, data-intensive ML can incentivize further data collection, thus leading to greater interferences with privacy and also the risk of de-anonymization. Moreover, the use of AI to analyze mass amounts of personal data is also linked to infringements on other rights, including freedom of opinion and expression, freedom of association and peaceful assembly, and the right to an effective remedy.46

Inequalities, discrimination and bias

When the data on which an AI model is trained are incomplete, biased or otherwise inadequate, it may result in the system producing discriminatory or unfair decisions and outputs.47 Biases and other flaws in the data can infect a system at several different stages: in the initial framing of the problem (e.g., a proxy variable is chosen that is linked to socioeconomic or racial characteristics); when the data are collected (e.g., a marginalized group is underrepresented in the training data); and when the data are prepared.48 In some cases, the inherent biases of the developers themselves can be unintentionally coded into a model. There have been several high-profile incidents where ML systems have displayed racial or gender biases – for example, an ML tool used by Amazon for CV review that disproportionately rejected women, or facial recognition tools that are worse at recognizing non-white faces.49 In the humanitarian context, avoiding unwanted bias and discrimination is intimately related to the core humanitarian principle of impartiality,50 and the stakes for such discrimination can be especially high – determining, for instance, who receives critical aid, or even who lives and who dies.51 On a macro level, algorithms (including AI) can have the effect of “deepen[ing] existing inequalities between people or groups, and exacerbate[ing] the disenfranchisement of specific vulnerable demographics”. This is because “[a]lgorithms, more so than other types of data analysis, have the potential to create harmful feedback loops that can become tautological in nature, and go unchecked due to the very nature of an algorithm's automation”.52

Lack of contextual knowledge at the design phase

There is often a disconnect between the design and application stages of an AI project. This is especially critical if the system is to be applied in humanitarian contexts.53 The tools may be designed without adequate contextual knowledge; often they are developed to be suitable for business and marketing decision-making rather than for humanitarian aid in the developing world. Tools designed without taking into account certain cultural, societal and gender-related aspects can lead to misleading decisions that detrimentally impact human lives. For example, a system conceived or designed in Silicon Valley but deployed in a developing country may fail to take into account the unique political and cultural sensitivities of that country. The developer may be unaware that in country X, certain stigmatized groups are underrepresented or even “invisible” in a data set, and fail to account for that bias in the training model; or a developer working on a tool to be deployed in a humanitarian context may not be aware that migrant communities and internally displaced persons are frequently excluded from censuses, population statistics and other data sets.54

Lack of expertise and last-mile implementation challenges

Insufficient expertise or training on the part of those deploying AI and other data-driven tools is associated with a number of human rights risks. This applies in the public sector, generally, where it is widely acknowledged that data fluency is lacking.55 This may result in a tendency to incorrectly interpret a system's output, overestimate its predictive capacity or otherwise over-rely on its outputs, such as by allowing the system's “decisions” to supersede human judgement. It may also create a risk that decision- and policy-makers will use AI as a crutch, employing AI analysis to add a veneer of objectivity or neutrality to their choices.

These risks are further exacerbated in the developing-country and humanitarian contexts, where a lack of technical resources, infrastructure or organizational capacity may preclude the successful exploitation of an AI system.56 These so-called “last-mile implementation” challenges may elevate human rights risks and other failures, especially in humanitarian contexts. For example, shortcomings – whether anticipated or unanticipated – may increase the chance of human error, which can include anything from failing to audit the system to over-relying on, or misinterpreting, its insights. This, in turn, may lead to detrimental impacts, such as the failure to deliver critical aid, or even discrimination and persecution.

Lack of quality data

Trustworthy and safe AI depends on quality data. Without ready access to quality data sets, AI cannot be trained and used in a way that avoids amplifying the above risks. However, the degree of availability and accessibility of data often reflects social, economic, political and other inequalities.57 In many development and humanitarian contexts, it is far more difficult to conduct quality data collection. This increases the risks that an AI system will produce unfair outcomes.58 While data quality standards are not new – responsible technologists have long since developed principles and best practices for quality data59 – there remains a lack of adequate legal frameworks for enabling access to usable data sets. As the Secretary-General commented in his Roadmap, “[m]ost existing digital public goods [including quality data] are not easily accessible because they are often unevenly distributed in terms of the language, content and infrastructure required to access them”.60

Over-use of AI

The analytical and predictive capabilities of AI systems can make them highly attractive “solutions” to difficult problems, both for resource-strained practitioners in the field and for those seeking to raise funds for these projects. This creates the risk that AI may be overused, including when less risky solutions are available.61 For one, there is widespread misunderstanding about the capabilities and limitations of AI, including its technical limitations. The popular depiction of AI in the media tends to be of all-powerful machines or robots that can solve a wide range of analytical problems. In reality, AI projects tend to be highly specialized, designed only for a specific use in a specific context on a specific set of data. Due to this misconception, users may be unaware that they are interacting with an AI-driven system. In addition, while AI is sometimes capable of replacing human labour or analysis, it is generally an inappropriate substitute for human decision-making in highly sensitive or high-stakes contexts. For instance, allowing an AI-supported system to make decisions on criminal sentencing, the granting of asylum62 or parental fitness – cases where fundamental rights and freedoms are at stake, and where impacted individuals may already be traumatized or distressed – can undermine individual autonomy, exacerbate psychological harm and even erode social connections.63

Private sector influence

Private sector technology companies are largely responsible for developing and deploying the AI systems that are used in the development and humanitarian sectors, often by way of third-party vendor contracts or public–private partnerships. This creates the possibility that, in certain cases, corporate interests may overshadow the public interest. For example, the profit-making interest may provide a strong incentive to push for an expensive, “high-tech” approach where a “low-tech” alternative may be better suited for the environment and purposes at hand.64 Moreover, close cooperation between States and businesses may undermine transparency and accountability, for example when access to information is inhibited on the basis of contractual agreements or trade secret protections. The deep involvement of corporate actors may also lead to the delegation of decision-making on matters of public interest. For example, there is a risk that humanitarian actors and States will “delegate increasingly complex and onerous censorship and surveillance mandates” to companies.65

Perpetuating and deepening inequalities

Deploying complex AI systems to support services for marginalized people or people in vulnerable positions can at times have the perverse effect of entrenching inequalities and creating further disenfranchisement. Biased data and inadequate models are one of the major problems in this regard, as discussed above, but it is important to recognize that these problems can in turn be seen as expressions of deeply rooted divides along socio-economic, gender and racial lines – and an increased deployment of AI carries the real risk of widening these divides. UNESCO has recently made this point, linking it to the effects of AI on the distribution of power when it stated that “[t]he scale and the power generated by AI technology accentuates the asymmetry between individuals, groups and nations, including the so-called ‘digital divide’ within and between nations”.66 Corporate capture, as just addressed, can be one of the most important contributors to this development. Countering this trend is no easy task and will require political will, collaboration, open multi-stakeholder engagement, strengthening of democratic governance of societies and promoting human rights in order to empower the people to take an active role in shaping the technological and regulatory environment in which they live.

Intersectional considerations

Some of these challenges distinguish AI systems from other technologies that we have regulated in the past, and therefore may require new solutions. However, it is worth noting that some of the underlying challenges are hardly new. In this regard, we may sometimes glean best practices on governing AI from other fields. For example, data privacy and data security risks and standards developed to protect information have been in existence for a long time. It is true that as the technology develops and more data are generated, new protections need to be developed or old ones updated to reflect the new challenges. Data security remains one of the key considerations in humanitarian work given the sensitivity of the data being collected and processed.

In addition, many of the challenges facing AI in humanitarian aid have been addressed by practitioners in the wider “tech for development” field,67 such as the challenges associated with last-mile implementation problems, as discussed above. Another perennial challenge is that development or humanitarian projects must sometimes weigh the risks of partnering with governments that have sub-par human rights records. This is undoubtedly true for powerful tools like AI. An AI system designed for a socially beneficial purpose – such as the digital contact tracing of individuals during a disease outbreak, used for containment purposes – could potentially be used by governments for invasive surveillance.68

Additionally, while all the above challenges are quite common and may lead to potential harms, the organizational context in which these AI systems or processes are embedded is an equally important determinant of their risks. Regardless of a system's analytical or predictive power in isolation (whether it involves a simple algorithm or complex neural networks), we can expect drastically different benefits and risks of harms depending on the nature and degree of human interaction with, or oversight of, that system.

The challenges described above are not merely theoretical – there are already countless real-world examples where advanced AI systems have caused serious harm. In some of the highest-profile AI mishaps to date, the implementer was a government agency or other public sector actor that sought to improve or streamline a public service. For example, a recent trend is the use of algorithmic analysis by governments to determine eligibility for welfare benefits or root out fraudulent claims.69 In Australia, the Netherlands and the United States, systemic design flaws or inadequate human oversight – among other issues – have resulted in large numbers of people being deprived their rights to financial assistance, housing or health.70 In August 2020, the UK Home Office decided to abandon a decision-making algorithm it had deployed to screen visa applicants over allegations of racial bias.71

We know relatively little about the harms that have been caused by the use of AI in humanitarian contexts. As the DSEG observed in its report, there remains “a lack of documented evidence” of the risks and harms of AI “due to poor tracking and sharing of these occurrences” and a “general attitude not to report incidents”.72 While the risks outlined above have been borne out in other contexts (such as social welfare), in humanitarian contexts there is at least evidence about the potential concerns associated with biometrics and the fears of affected peoples.

A recent illustrative case study is that of Karim, a psychotherapy chatbot developed and tested on Syrian refugees living in the Zaatari refugee camp. Experts who spoke to researchers from the Digital Humanitarian Network expressed concern that the development of an AI therapy chatbot, however advanced, reflected a poor understanding of the needs of vulnerable people in that context.73 In addition to linguistic and logistical obstacles that became evident during the pilot, the experts argued that a machine therapist was not, in fact, better than having no therapist at all – that it actually risked increasing subjects’ sense of alienation in the long term.74 Karim appears to be an example of what, according to the Humanitarian Technologies Project, happens when “there is a gap between the assumptions about technology in humanitarian contexts and the actual use and effectiveness of such technology by vulnerable people”.75

The above challenges show that piloting unproven AI tools on vulnerable populations may potentially gravely undermine human rights when those tools are ill-suited for the context or when those deploying the tools lack expertise on how to use them.76

Approaches to governing AI: Beyond ethics

The above examples illustrate the potential for AI to both serve human interests and to undermine them, if proper safeguards are not put in place and risks are unaccounted for. For these reasons, the technologists designing these systems and humanitarian and development experts deploying AI are increasingly cognizant of the need to infuse human rights and ethical considerations into their work. Accordingly, there is a growing body of technical specifications and standards that have been developed to ensure AI systems are “safe”, “secure” and “trustworthy”.77 But ensuring that AI systems serve human interests is about more than just technical specifications. As McGregor, Murray and Ng have argued, a wider, overarching framework should be in place to incorporate risks of harm at every stage of the system's life cycle and to ensure accountability when things go wrong.78

Early AI governance instruments, ostensibly developed to serve this guiding role, have mostly taken the form of “AI codes of ethics”.79 These codes tend to consist of guiding principles that the organization is committed to honouring, akin to a constitution for the development and use of AI. As their names suggest, these codes tend to invoke ethical principles like fairness and justice, rather than guaranteeing specific human rights.80 Indeed, human rights – the universal and binding system of principles and treaties that all States must observe – have been conspicuously absent from many of these documents.81 According to Philip Alston, the UN Special Rapporteur on Extreme Poverty and Human Rights, many AI codes of ethics include token references to human rights – for example, including a commitment to respecting “human rights” as a stand-alone principle – but fail to capture the substantive rights provided for by the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) and human rights treaties.82

The shortcomings of this “ethics-first approach” are increasingly apparent. One of the key gaps is the absence of accountability mechanisms for when ethical principles are violated.83 Most codes of ethics provide no answer for who bears the cost of an “unethical” use of technology, what that cost should be, or how violations would be monitored and enforced. Moreover, it is not clear how an individual who feels wronged can determine that a wrong has indeed occurred, or what procedure they can follow to seek redress.84 Unlike human rights law, codes of ethics typically do not make it clear how to balance the interests of disparate groups or individuals, some of whom may benefit from an AI system to the detriment of others. While AI codes of ethics may constitute an important first step towards more binding governance measures, they require further articulation as specific, enforceable rights to have any real impact.

Human rights as the baseline

For these and other reasons, there was broad consensus across the consultations held by UN Global Pulse and UN Human Rights85 that human rights should form the basis of any effective AI governance regime. International human rights law (IHRL) provides a globally legitimate and comprehensive framework for predicting, preventing and redressing the aforementioned risks and harms. As McGregor et al. argue, IHRL provides an “organizing framework for the design, development and deployment of algorithms, and identifies the factors that States and businesses should take into consideration in order to avoid undermining, or violating, human rights”.86 Far from being a stand-alone and static set of “rules”, this framework “is capable of accommodating other approaches to algorithmic accountability – including technical solutions – and … can grow and be built on as IHRL itself develops, particularly in the field of business and human rights”.87

The case for IHRL can be broken down into several discrete aspects that make this framework particularly appropriate to the novel risks and harms of AI. Firstly, unlike ethics, IHRL is universal.88 IHRL offers a common vocabulary and set of principles that can be applied across borders and cultures, ensuring that AI serves shared human values as embodied in the UDHR and other instruments. There is no other common set of moral or legal principles that resonates globally like the UDHR.89 In a world where technology and data flow almost seamlessly across borders, and where technology cannot be governed effectively within a single jurisdiction, this universal legitimacy is essential.

Secondly, the international human rights regime is binding on States. Specifically, it requires them to put a framework in place that “prevents human rights violations, establishes monitoring and oversight mechanisms as safeguards, holds those responsible to account, and provides a remedy to individuals and groups who claim their rights have been violated”.90 At the international level, the IHRL regime also offers a set of built-in accountability and advocacy mechanisms, including the HRC and the treaty bodies, which have complaints mechanisms and the ability to review the performance of member States; the Special Procedures of the HRC (namely the working groups and Special Rapporteurs), which can conduct investigations and issue reports and opinions;91 and, increasingly, the International Court of Justice, which has begun to carve out a bigger role for itself in human rights and humanitarian jurisprudence.92 Moreover, regional human rights mechanisms have assumed a key role in developing the human rights system, including by providing individuals with the opportunity to bring legal actions against perpetrators of human rights violations.93

Thirdly, IHRL focuses its analytical lens on the rights holder and duty bearer in a given context, enabling much easier application of principles to real-world situations.94 Rather than aiming for broad ideals like “fairness”, human rights law calls on developers and implementers of AI systems to focus in on who, specifically, will be impacted by the technology and which of their specific fundamental rights will be implicated. This is an intensely pragmatic exercise that involves translating higher ideals into narrowly articulated risks and harms. Relatedly, many human rights accountability mechanisms also enable individuals to assert their rights by bringing claims before various adjudicating bodies. Of course, accessing a human rights tribunal and formulating a viable claim is much easier said than done. But at the very least, human rights provide these individuals with the “language and procedures to contest the actions of powerful actors”, be they States or corporations.95

Fourthly, in defining specific rights, IHRL also defines the harms that need to be avoided, mitigated and remedied.96 In doing so, it identifies the outcomes that States and other entities – including development and humanitarian actors – can work towards achieving. For example, the UN's Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights has developed standards for “accessibility, adaptability and acceptability” that States should pursue in their social protection programmes.97

Finally, human rights law and human rights jurisprudence provide a framework for balancing rights that come into conflict with each other.98 This is essential when deciding whether to deploy a technological tool that entails both benefits and risks. In these cases, human rights law provides guidance on when and how certain fundamental rights can be restricted – namely, by applying the principles of legality, legitimacy, necessity and proportionality to the proposed AI intervention.99 In this way, IHRL also helps identify red lines – that is, actions that are out of bounds.100 This framework would be particularly helpful for humanitarian organizations trying to decide if and when a certain AI capability (such as a facial recognition technology) should be avoided entirely.

The need for a balancing framework is arguably evident in most humanitarian applications of AI. The balancing approach has been incorporated into UN Global Pulse's Risks, Harms and Benefits Assessment, which prompts the implementers of an AI or data analytics project not only to consider the privacy risks and likelihood, magnitude and severity/significance of potential harms, but also to weigh these risks and harms against the predicted benefits of the project. IHRL jurisprudence helps guide the use of powerful AI tools in these contexts, dictating that such use is only acceptable so long as it is prescribed by law, in pursuit of a legitimate aim, and is necessary and proportionate to that aim.101 In pursuing this balance, decision-makers can look to decades of IHRL jurisprudence for insight on how to resolve tensions between conflicting rights, or between the rights of different individuals.102 Other examples of tools and guidance103 that incorporate the balancing framework include the International Principles on the Application of Human Rights to Communication Surveillance104 and the OCHA Guidance Note on data impact assessments.105

Gaps in Implementing IHRL: Private sector accountability

One major limitation of IHRL is that it is only binding on States. Individuals can therefore only bring human rights claims vertically – against the State – rather than horizontally – against other citizens, organizations or, importantly, companies.106 This would seem to be a problem for AI accountability because the private sector plays a leading role in developing AI and is responsible for the majority of innovation in this field. Of course, States are required under IHRL to incorporate human rights standards into their domestic laws; these, in turn, would regulate the private sector. But we know from experience that this does not always happen, and that even when States do incorporate human rights law into their domestic regulations, they are only able to enforce the law within their respective jurisdictions. Yet many major technology companies operate transnationally, including in countries where human rights protections are weaker or under-enforced.

Nonetheless, human rights law has powerful moral and symbolic influence that can shape public debate, sharpen criticism and help build pressure on companies, and human rights responsibilities of companies that are independent from States’ ability or willingness to fulfil their own human rights obligations are increasingly recognized.107 There are a number of mechanisms and levers of pressure by which private companies are incentivized to comply.

Emerging as an international norm for rights-respecting business conduct are the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs).108 The UNGPs are conceptualizing the responsibility of businesses to respect human rights along all their business activities, and they call on companies to carry out human rights due diligence in order to identify, address and mitigate adverse impacts on human rights in the procurement, development and operation of their products.109 A growing chorus of human rights authorities have reiterated that these same obligations apply to algorithmic processing, AI and other emerging digital technologies110 – most recently, in the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights’ report on the use of technologies such as facial recognition in the context of peaceful protests.111 UN Human Rights is also in the process of developing extensive guidance on the application of the UNGPs to the development and use of digital technologies.112 A growing number of leading AI companies, such as Element AI, Microsoft and Telefonica, have also begun applying the UNGPs to their AI products.113

A second critique of a human rights-based approach to AI is that prioritizing human rights at every stage of the deployment cycle will hinder innovation. There is some truth to this – emphasizing human rights may occasionally delay or even preclude the deployment of a risky product. However, it might also prevent later, even more costly effects of managing the potential fallout of human rights violations.114 Moreover, the value of a human rights approach is not merely in ensuring compliance but in embedding human rights in the very conception, development and roll-out of a project. Prioritizing human rights at every stage of the development process should therefore reduce the number of instances where a product ends up being too risky to deploy.

The role of ethics

While human rights should set the outer boundaries of AI governance, ethics has a critical role to play in responsible AI governance. Even many ardent advocates of a human rights-based approach to AI acknowledge the reinforcing role that ethical principles can play in augmenting or complementing human rights. In the context of AI, “ethics” typically refers to the so-called FAccT principles: fairness, accountability and transparency (sometimes also called FATE, where the E stands for “ethics”).115 To some, the FAccT approach contrasts with the rigidity of law, eschewing hard-and-fast “rights” in favour of broader consideration of what impact a system will have on society.116 In this way, ethics is often seen as more adaptable to technological evolution and the modern world; IHRL principles, by contrast, were developed decades ago, long before the proliferation of AI and ML systems.

Yet while there are important distinctions between a human rights-based and an ethics-based approach, our consultations have revealed that the “human rights versus ethics” divide pervading AI policy may in some sense be a false dichotomy.117 It is worth underlining that human rights and ethics have essentially the same goals. As Access Now has succinctly observed, any “unethical” use of AI will also likely violate human rights (and vice versa).118 That said, human rights advocates are rightly concerned about the phenomenon of “ethics-washing”,119 whereby the makers of technology – often private companies – self-regulate through vague and unenforceable codes of ethics. Technical experts, for their part, are often sceptical that “rigid” human rights law can be adapted to the novel features and risks of harm of AI and ML. While both of these concerns may be valid, these two approaches can actually complement, rather than undermine, each other.

For example, it can take a long time for human rights jurisprudence to develop the specificity necessary to regulate emerging digital technologies, and even longer to apply human rights law as domestic regulation. In such cases where law does not provide clear or immediate answers for AI developers and implementers, ethics can be helpful in filling the gaps;120 however, this is a role that the interpretation of the existing human rights provisions and case law can play as well. In addition, ethics can raise the bar above the minimum standards set by a human rights framework or help incorporate principles that are not well established by human rights law.121 For instance, an organization developing AI tools might commit to guaranteeing human oversight of any AI-supported decision – a principle not explicitly stated in any human rights treaty, but one that would undoubtedly reinforce (and implement) human rights.122 Other organizations seeking to ensure that the economic or material benefits of AI are equally distributed may wish to incorporate the ethical principles of distributive justice123 or solidarity124 in their use of AI.

When AI is deployed in development and humanitarian contexts, the goal is not merely to stave off regulatory action or reduce litigation risk through compliance. In fact, there may be little in the way of enforceable regulation or oversight that applies in development and humanitarian contexts. Rather, these actors are seeking to materially improve the lives and well-being of targeted communities. AI that fails to protect the rights of those impacted may instead actively undermine this essential development and humanitarian imperative. For these reasons, development and humanitarian actors are becoming more ambitious in their pursuit of AI that is designed in rights-respecting, ethical ways.125

Principles and tools

A human rights-based framework will have little impact unless it is operationalized in the organization's day-to-day work. This requires developing tools and mechanisms for the design and operation of AI systems at every stage of the product lifecycle – and in every application. This section will introduce several such tools that were frequently endorsed as useful or essential in our consultations and interviews.

In his Strategy on New Technology, the UN Secretary-General noted the UN's commitment to both “deepening [its] internal capacities and exposure to new technologies” and “supporting dialogue on normative and cooperation frameworks”.126 The Secretary-General's High-Level Panel on Digital Cooperation made similar recommendations, calling for enhanced digital cooperation to develop standards and principles of transparency, explainability and accountability for the design and use of AI systems.127 There has also been some early work within the UN and other international organizations on the development of ethical principles and practical tools.128

Internal AI principles

Drafting a set of AI principles, based on human rights but augmented by ethics, can be helpful in guiding an organization's work in this area – and, ultimately, in operationalizing human rights. The goal of such a “code” would be to provide guidance to every member of the team in order to ensure that human needs and rights are constantly in focus at every stage of the AI life cycle. More importantly, the principles could also undergird any compliance tools or mechanisms that the organization subsequently develops, including risk assessments, technical standards and audit procedures. These principles should be broad enough that they can be interpreted as guidance in novel situations – such as the emergence of a technological capacity not previously anticipated – but specific enough that they are actionable in the organization's day-to-day work.

The UN Secretary-General has recommended the development of AI that is “trustworthy, human-rights based, safe and sustainable and promotes peace”.129 While an organization's guiding principles should be anchored in these four pillars, there is potential for substantial variation depending on the nature and context of an organization's work. Our consultations suggested that an effective set of principles would be rooted in human rights principles – interpreted or adapted into the AI context – along with complementary ethics principles which provide flexibility to address new challenges that arise as the technology develops.

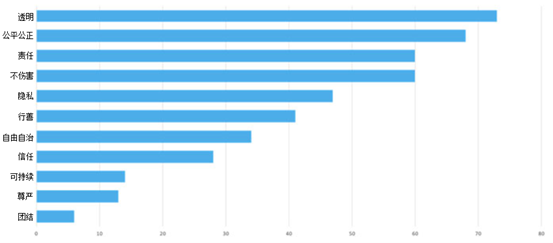

While suggesting a complete set of principles is beyond the scope of this article, there is an emerging consensus that certain challenges deserve special attention. Three of these challenges – non-discrimination, transparency and explainability, and accountability – will be discussed in more detail below. Other commonly cited principles include human-centred design, human control or oversight, inclusiveness and diversity, privacy, technical robustness, solidarity, sustainability, democracy, good governance, awareness and literacy, ubuntu, and banning lethal autonomous weapons systems. A table of the principles that appear most frequently in AI ethics guidelines, based on a 2019 analysis by René Clausen Nielsen of UN Global Pulse, is shown in Figure 1.

Of course, adopting a code of ethics does not, in itself, guarantee that an organization will prioritize human rights in developing AI tools. These principles must be operationalized to have any real impact. The foundational step in this operationalization should be a binding policy commitment to human rights adopted at the executive level. Moreover, the implementation of the commitment needs to be accompanied and guided by appropriate management and oversight structures and processes. Further steps that could be taken would include the translation into technical standards that allow for quality control and auditing. For example, some experts have proposed technical standards for algorithmic transparency, or implementing rules that automatically detect potentially unfair outcomes from algorithmic processing.130 Moreover, the code would have to be developed in a way that facilitates and informs the creation of concrete tools and procedures for mitigating human rights risks at every stage of the AI life cycle. For example, it could be an element of the human rights due diligence tools described below.

While each of the aforementioned principles may indeed be essential, our consultations focused on three interrelated ethical principles that are firmly anchored in IHRL and require further elaboration and more careful implementation: non-discrimination, transparency and explainability, and accountability. Organizations using AI for humanitarian aid need to develop policies and mechanisms to ensure that these systems do not have discriminatory impact; that their decisions are capable of being understood and explained, at least to a level adequate for the risks involved; and that there is accountability for harms associated with their operation. This is especially crucial in operations where AI is used to support the vulnerable. While these are not the only governance challenges associated with AI, they offer a starting point for conversations about what makes AI different from other technologies and why it poses unique challenges for human rights.131

Non-discrimination

One of the key principles that humanitarian organizations need to ensure is non-discrimination. AI systems tend to reflect existing power relations and dynamics, and their deployment may risk creating new inequalities and dependencies or entrenching those that are already present. Therefore, it is important to note as a starting point that any decision to develop and deploy an AI system in a humanitarian context needs to take a holistic view of how this system will operate in the target environment and how it will affect people's lives, with a strong focus on those in vulnerable positions.

A few solutions were suggested during our consultations and research. Above all, diversity and inclusion are absolutely critical to ensuring that AI systems are used in a non-discriminatory manner. This principle should pervade every aspect of AI development and use, from incorporating diverse perspectives in the teams designing and deploying AI systems to ensuring that training data is representative of target populations. Meaningful comprehensive consultations with representatives of affected groups are essential for preventing exclusionary and discriminatory effects of deployed AI solutions.

Second, capacity-building and knowledge sharing are urgently needed. Practitioners that we consulted raised the need for a good-faith intermediary to coordinate knowledge sharing across the world and provide practical advice on how to address bias questions. Such an entity could compile best practices in the AI for development and humanitarian fields and identify areas where experimentation with AI may need to be barred. The intermediary could serve as a discovery resource for organizations using AI that do not know how to interrogate their AI systems and/or lack the resources to do so. Many organizations need someone who can help them troubleshoot potential discrimination concerns by packaging the data and interrogating possible bias.

Third, given that the risks of unwanted discriminatory impact can never be reduced to zero, certain areas may be deemed too risky or uncertain for AI systems to play a central role (e.g., making final determinations). These may include criminal justice, social welfare and refugee/asylum processing, where various pilot projects and cases studies have already flagged problematic discriminatory implications with direct impact on human lives. Our consultations suggested that, in such cases, organizations could make use of red-line bans and moratoria.132

Transparency and explainability

Transparency and explainability of AI systems are prerequisites to accountability. However, full transparency into many ML and DL systems is not possible.133 When a model is unsupervised, it will be capable of classifying, sorting or ranking the data based on a set of rules or patterns that it identifies, and the humans who created this model will not always be able to tell how or why the resulting analysis was arrived at.134 This means that, in order to make use of this technology, organizations will need to carefully assess if and how these largely obscure or unexplainable systems can be used in a way that augments, rather than undermines, human rights.

There are at least two different types of transparency, both of which are essential to ensuring accountability. The first is technical transparency – that is, transparency of the models, algorithms and data sets that comprise an AI system. The second is organizational transparency, which deals with questions such as whether an AI system is being used for a particular purpose, what kind of system or capability is being used, who funded or commissioned the system and for what purpose, who built it, who made specific design decisions, who decided where to apply it, what the outputs were, and how those outputs were used.135 While the two are related, each type of transparency requires its own set of mechanisms and policies to ensure that a system is transparent and explainable.

To address and ensure the principle of transparency, our consultations and research supported the idea of human-in-the-loop as a foundational principle. Human-in-the-loop is the practice of embedding a human decision-maker into every AI-supported decision.136 This means that, even in cases where DL is being leveraged to generate powerful predictions, humans are responsible for operationalizing that prediction and, to the extent possible, auditing the system that generated it.137 In other words, humans hold ultimate responsibility for making decisions, even when they rely heavily on output or analysis generated by an algorithm.138 However, effective human-in-the-loop requires more than just having a human sign off on major decisions. Furthermore, organizations also need to scrutinize how human decision-makers interact with AI systems and ensure that human decision-makers have meaningful autonomy within the organizational context.139

Accountability

Accountability enables those affected by a certain action to demand an explanation and justification from those acting and to obtain adequate remedies if they have been harmed.140 Accountability can take several different forms.141 Technical accountability requires auditing of the system itself. Social accountability requires that the public have been made aware of AI systems and have adequate digital literacy to understand their impact. Legal accountability requires having legislative and regulatory structures in place to hold those responsible for bad outcomes to account.

Firstly, there is a strong need for robust oversight mechanisms to monitor and measure progress on accountability mechanisms across organizations and contexts. Such a mechanism could be set up at the national, international or industry level and would need to have substantial policy, human rights and technical capacity. Another idea is for this or another specialized entity to carry out certification or “kitemarking” of AI tools and systems, whereby those with high human rights scores (based on audited practices) are “certified” both to alert consumers and, potentially, open the door to partnerships with governments, international organizations, NGOs and other organizations committed to accountable, rights-respecting AI.142

Secondly, while legal frameworks develop, self-regulation will continue to play a significant role in setting standards for how private companies and other organizations operate. However, users and policy-makers could monitor companies through accountability mechanisms and ensure that industry is using its full capacity to ensure human rights.

Thirdly, effective remedies are key elements of accountable AI frameworks. In particular, in the absence of domestic legal mechanisms, remedies can be provided at the company or organization level through internal grievance mechanisms.143 Whistle-blowing is also an important tool for uncovering abuses and promoting accountability, and proper safeguards and channels should be put in place to encourage and protect whistle-blowers.

Finally, ensuring good data practices is a critical component of AI accountability. Our consultations revealed several mechanisms for data accountability, including quality standards for good data and mechanisms to improve access to quality data, such as mandatory data sharing.

Human rights due diligence tools

It is increasingly recognized that human rights due diligence (HRDD) processes, conducted throughout the life cycle of an AI system, are indispensable for identifying, preventing and mitigating human rights risks linked to the development and deployment of AI systems.144 Such processes can be helpful in determining necessary safeguards and in developing effective remedies when harm does occur. HRDD gives a rights-holder perspective a central role. Meaningful consultations with external stakeholders, including civil society, and with representatives of potentially impacted individuals and groups, in order to avoid project-driven bias, are essential parts of due diligence processes.145

Human rights impact assessments

In order for States, humanitarian organizations, businesses and other actors to meet their respective responsibilities under IHRL, they need to identify human rights risks stemming from their actions. HRDD commonly builds on a human rights impact assessment (HRIA) for identifying potential and actual adverse impacts on human rights related to actual and planned activities.146 While the HRIA is a general tool, recommended for all companies and sectors by the UNGPs, organizations are increasingly applying the HRIA framework to AI and other emerging digital technologies147 . The Secretary-General's Roadmap announced plans for UN Human Rights to develop system-wide guidance on HRDD and impact assessments in the use of new technologies.148 HRIAs should ideally assist practitioners in identifying the impact of their AI interventions, considering such factors as the severity and type of impact (directly causing, contributing to, or directly linked), with the goal of guiding decisions on whether to use the tool (and if so, how) or not.149

Other potentially relevant tools for identifying a humanitarian organization's adverse impact on human rights include data protection impact assessments, which operationalize best practices in data privacy and security; and algorithmic impact assessments, which aim to mitigate the unique risks posed by algorithms. Some tools are composites, such as Global Pulse's Risks, Harms and Benefits Assessment, which incorporates elements found in both HRIAs and data protection impact assessments.150 This tool allows every member of a team – including technical and non-technical staff – to assess and mitigate risks associated with the development, use and specific deployment of a data-driven product. Importantly, the Risks, Harms and Benefits Assessment provides for the consideration of a product's benefits – not only the risks – and hence reflects the imperative of balancing interests, as provided for by human rights law.

The advantage of these tools is that they are adaptable to technological change. Unlike regulatory mechanisms or red-line bans, HRDD tools are not limited to specific technologies or technological capacities (e.g., facial recognition technology) but rather are designed to “[pre-empt] new technological capabilities and [allow] space for innovation”.151 In addition, well-designed HRDD tools recognize that context specificity is key when assessing human rights risk, hence the need for a case-specific assessment. Regardless of which tool, or combination of tools, makes the most sense in a given situation, it will be necessary to ensure that the assessment has been designed or updated to accommodate AI-specific risks. It may also be useful to adapt tools to specific development and humanitarian sectors, such as public health or refugee response, given the unique risks that are likely to arise in those areas.

It is critical to emphasize that HRIAs should be part of the wider HRDD process whereby identified risks and impacts are effectively mitigated and addressed in a continuous process. The quality of an HRDD process will increase when “knowing and showing” is supported by governance arrangements and leadership actions to ensure that a company's policy commitment to respecting human rights is “embedded from the top of the business enterprise through all its functions, which otherwise may act without awareness or regard for human rights”.152 HRDD should be carried out at all stages of the product cycle and should be used by all parties involved in a project. Equally important is that this framework involves the entire organization – from data scientists and engineers to lawyers and project managers – so that diverse expertise informs the HRDD process.

Explanatory models

In addition, organizations could make use of explanatory models for any new technological capability or application.153 The purpose of an explanatory model is to require technical staff, who better understand how a product works, to explain the product in layman's terms to their non-technical colleagues. This exercise serves both to train data scientists and engineers to think more thoroughly about the inherent risks in what they are building, and to enable non-technical staff – including legal, policy and project management teams – to make an informed decision about whether and how to deploy it. In this way, explanatory models could be seen as a precursor to the risk assessment tools described above.

Due diligence tools for partnerships

An important caveat to the use of these tools is that they are only effective if applied across every link in the AI design and deployment chain, including procurement. Many organizations innovating in this field rely on partnerships with technology companies, governments and civil society organizations in order to build and deploy their products. To ensure proper human rights and ethical standards, it is important that partnerships that support humanitarian and development missions are adequately vetted. The challenge in the humanitarian and development sectors is that most due diligence tools and processes do not (yet) adequately cover AI-related challenges. To avoid potential risks of harm, such procedures and tools need to take into account the technological challenges involved and ensure that partners, particularly private sector actors, are committed to HRDD best practices, human rights and ethical standards. UN Global Pulse's Risks, Harms and Benefits Assessment tool is one example of this.154

Moreover, because of the risks that may arise when AI systems are used by inadequately trained implementers, organizations need to be vigilant about ensuring downstream human rights compliance by all implementing partners. As UN Human Rights has observed, most human rights harms related to AI “will manifest in product use”, whether intentionally – for instance, an authoritarian government abusing a tool to conduct unlawful surveillance – or inadvertently, through unanticipated discrimination or user error. This means an AI developer cannot simply hand off a tool to a partner with instructions to use it judiciously. That user, and any third party with whom they partner, must commit to thorough, proactive and auditable HRDD through the tool's life cycle.

Public engagement

An essential component of effective HRDD is engagement with the populations impacted by an AI tool. Humanitarian organizations should prioritize engagement with rights holders, affected populations, civil society and other relevant stakeholders in order to obtain a comprehensive, nuanced understanding of the needs and rights of those potentially impacted. This requires proactive outreach, including public consultations where appropriate, and also making available accessible communication channels for affected individuals and communities. As Special Rapporteur David Kaye has recommended, “public consultations and engagement should occur prior to the finalization or roll-out of a product or service, in order to ensure that they are meaningful, and should encompass engagement with civil society, human rights defenders and representatives of marginalized or underrepresented end users”. In some cases, where appropriate, organizations may choose to make the results of these consultations (along with HRIAs) public.155

Audits

Development and humanitarian organizations can ensure that AI tools – whether developed in-house or by vendors – are externally and independently reviewed in the form of audits.156 Auditability is critical to ensuring transparency and accountability, while also enabling public understanding of, and engagement with, these systems. While private sector vendors are traditionally resistant to making their products auditable – citing both technical feasibility and trade-secret concerns – numerous models have been proposed that reflect adequate compromises between these concerns and the imperative of external transparency.157 Ensuring and enabling auditability of AI systems would ultimately be the domain of government regulators and private sector developers, and development and humanitarian actors could promote and encourage its application and adoption.158 For example, donors or implementers could make auditability a prerequisite for grant eligibility.

Other institutional mechanisms

There are several institutional mechanisms that can be put in place to ensure that human rights are encoded into an organization's DNA. One principle that has already been discussed is human-in-the-loop, whereby human decision-makers are embedded in the system to ensure that no decisions of consequence are made without human oversight and approval. Another idea would be to establish an AI human rights and ethics review board, which would serve a purpose analogous to the review boards used by academic research institutions.159 The board, which would ideally be composed of both technical and non-technical staff, would be required to review and sign off on any new technological capacity – and ideally, any novel deployment of that capacity – prior to deployment. In order to be effective as a safeguard, the board would need real power to halt or abort projects without fear of repercussion. Though review boards could make use of the HRDD tools introduced above, their review of a project would constitute a separate, higher-level review than the proactive HRDD that should be conducted at every stage of the AI life cycle. Entities should also consider opening up to regular audits of their AI practices and make summaries of these reports available to their staff, and, where appropriate, to the public. Finally, in contexts where the risks of a discriminatory outcome include grave harm to individuals’ fundamental rights, the use of AI may need to be avoided entirely – including through red-line bans.

Capacity-building and knowledge sharing

The challenge of operationalizing human rights and ethical principles in the development of powerful and unpredictable technology is far beyond the capabilities of a single organization. There is an urgent need for capacity-building, especially in the public and NGO sectors. This is true both of organizations deploying AI and those charged with overseeing it. Many data protection authorities, for instance, may lack the resources and capacity to take on this challenge in a competent and comprehensive way.160 Humanitarian agencies may need help applying existing laws and policies to AI and identifying gaps that need to be filled.161 In addition, the staff at organizations using AI may need to expand training and education in the ethical and human rights dimensions of AI and the technical operations of systems, in order to ensure trust in the humans designing and operating these systems (as opposed to just the system itself).

AI governance is a fundamentally transnational challenge, so in addition to organization-level capacity-building, effective AI governance will require international cooperation. At the international level, a knowledge-sharing portal operated by traditional actors like the UN, and/or by technical organizations like the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, could serve as a resource for model HRDD tools, technical standards and other best practices.162 At the country level, experts have suggested that governments create an “AI ministry” or “centre of expertise” to coordinate efforts related to AI across the government.163 Such an entity would allow each country to establish governance frameworks that are appropriate for the country's cultural, political and economic context.

Finally, a key advantage of the human rights framework is the existence of accountability and advocacy mechanisms at the international level. Organizations should look to international human rights mechanisms, including the relevant HRC working groups and Special Rapporteurs, for exploration and articulation of the emerging risks posed by AI and best practices for mitigating them.164

Conclusion

As seen in various contexts, including the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, AI may have a role to play in supporting humanitarian missions, if developed and deployed in an inclusive and rights-respecting way. To ensure that the risks of these systems are minimized, and their benefits maximized, human rights principles should be embedded from the start. In the short term, organizations can take several critical steps. First, an organization developing or deploying AI in humanitarian contexts could develop a set of principles, based in human rights and supplemented by ethics, to guide its work with AI. These principles should respond to the specific contexts in which the organization works and may vary from organization to organization.

In addition, diversity and inclusivity are absolutely critical to preventing discriminatory outcomes. Diverse teams should be involved in an AI project from the earliest stages of development all the way through to implementation and follow-up. Further, it is important to implement mechanisms that guarantee adequate levels of both technical and organizational transparency. While complete technical transparency may not always be possible, other mechanisms – including explanatory models – can help educate and inform implementers, impacted populations and other stakeholders about the benefits and risks of an AI intervention, thereby empowering them to provide input and perspective on whether and how AI should be used and also enabling them to challenge the ways in which AI is used.165 Ensuring that accountability mechanisms are in place is also key, both for those working on systems internally and for those potentially impacted by an AI system. More broadly, engagement with potentially impacted individuals and groups, including through public consultations and by facilitating communication channels, is essential.

One of the foremost advantages of basing AI governance in human rights is that the basic components of a compliance toolkit already (mostly) exist. Development and humanitarian practitioners should adapt and apply established HRDD mechanisms, including HRIAs, algorithmic impact assessments, and/or UN Global Pulse's Risks, Harms and Benefits Assessment. These tools should be used at every stage of the AI life cycle, from conception to implementation.166 Where it becomes apparent that these tools are inadequate to accommodate the novel risks of AI systems, especially as these systems develop more advanced capabilities, they can be evaluated and updated.167 In addition, organizations could demand similar HRDD practices from private sector technology partners and refrain from partnering with vendors whose human rights compliance cannot be verified.168 Practitioners should make it a priority to engage with those potentially impacted by a system, from the earliest stages of conception through implementation and follow-up. To the extent practicable, development and humanitarian practitioners should ensure the auditability of their systems, so that decisions and processes can be explained to impacted populations and harms can be diagnosed and remedied. Finally, ensuring that a project uses high-quality data and that it follows best practices for data protection and privacy is necessary for any data-driven project.

- 1UN General Assembly, Roadmap for Digital Cooperation: Implementation of the Recommendations of the High-Level Panel on Digital Cooperation. Report of the Secretary-General, UN Doc. A/74/82, 29 May 2020 (Secretary-General's Roadmap), para. 6, available at: https://undocs.org/A/74/82 (all internet references were accessed in December 2020).

- 2See, for example, the initiatives detailed in two recent papers on AI and machine learning (ML) applications in COVID response: Miguel Luengo-Oroz , “Artificial Intelligence Cooperation to Support the Global Response to COVID-19”, Nature Machine Intelligence, Vol. , No. 6, 00; Joseph Bullock , “Mapping the Landscape of Artificial Intelligence Applications against COVID-19”, Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research, Vol. 69, 00, available at: www.jair.org/index.php/jair/article/view/116.

- 3Secretary-General's Roadmap, above note 1, para. 5.

- 4AI is “forecast to generate nearly $ trillion in added value for global markets by 2022, even before the COVID-19 pandemic, which experts predict may change consumer preferences and open new opportunities for artificial intelligence-led automation in industries, businesses and societies”. Ibid., para. 53.

- 5Lorna McGregor, Daragh Murray and Vivian Ng, “International Human Rights Law as a Framework for Algorithmic Accountability”, International and Comparative Law Quarterly, Vol. 68, No. 2, 2019, available at: https://tinyurl.com/yaflu6ku.

- 6See, for example, Yavar Bathaee, “The Artificial Intelligence Black Box and the Failure of Intent and Causation”, Harvard Journal of Law and Technology, Vol. 31, No. 2, 2018; Rachel Adams and Nora Ni Loideain, “Addressing Indirect Discrimination and Gender Stereotypes in AI Virtual Personal Assistants: The Role of International Human Rights Law”, paper presented at the Annual Cambridge International Law Conference 2019, “New Technologies: New Challenges for Democracy and International Law”, 19 June 2019, available at: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3392243.

- 7See, for example, Global Privacy Assembly, “Declaration on Ethics and Data Protection in Artificial Intelligence”, Brussels, 23 October 2018, available at: http://globalprivacyassembly.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/20180922_IC…; UN Global Pulse and International Association of Privacy Professionals, Building Ethics into Privacy Frameworks for Big Data and AI, 2018, available at: https://iapp.org/resources/article/building-ethics-into-privacy-framewo….

- 8For an overview, see Jessica Fjeld, Nele Achten, Hannah Hilligoss, Adam Nagy and Madhulika Srikumar, Principled Artificial Intelligence: Mapping Consensus in Ethical and Rights-based Approaches to Principles for AI, Berkman Klein Center Research Publication No. 2020-1, 14 February 2020.